Anorexia nervosa, commonly referred to as anorexia, is a complex and deeply misunderstood condition. While many perceive it solely through the lens of physical appearance or dramatic weight loss, anorexia is a psychological disorder with profound implications for mental and emotional well-being. In both clinical and public discourse, understanding that anorexia is a mental health disorder is crucial for promoting awareness, empathy, and effective treatment strategies. The persistent myth that anorexia is simply about vanity or dieting must be replaced with informed perspectives grounded in psychological science and compassionate care.

You may also like: How to Stop Emotional Eating and Regain Control: Mindful Nutrition Strategies That Support a Healthier Lifestyle

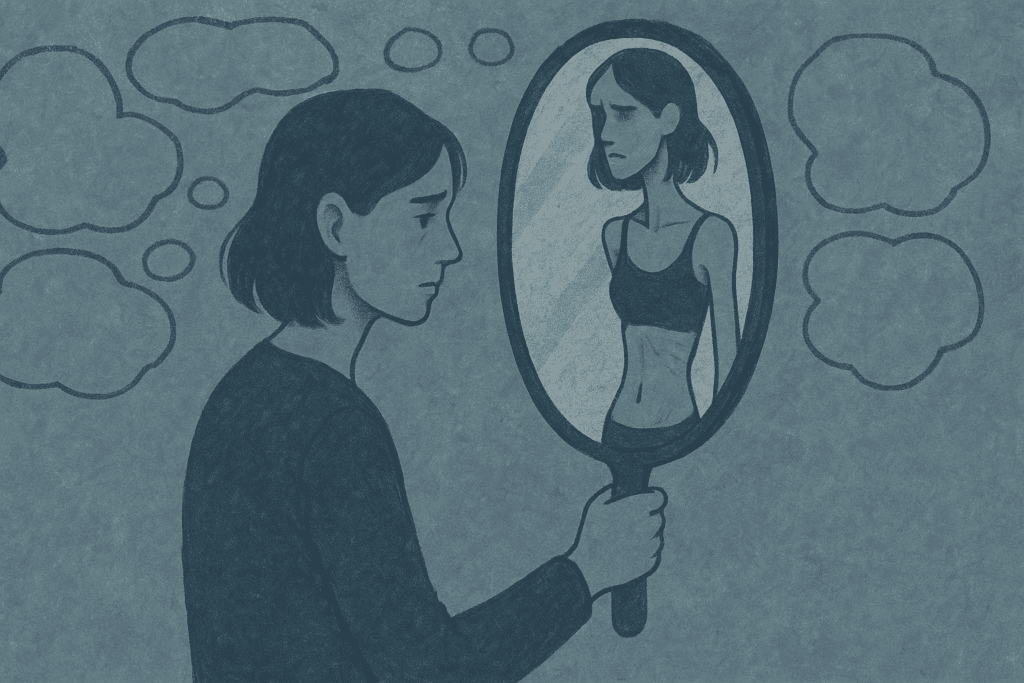

The question “is anorexia a mental health disorder?” deserves a clear and unequivocal answer. Yes, it is. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), the gold standard for psychiatric diagnosis, classifies anorexia as an eating disorder rooted in mental and emotional disturbances. People with anorexia experience a distorted body image, an intense fear of gaining weight, and a relentless pursuit of thinness, often to the point of self-starvation. These behaviors are not fleeting preferences but enduring patterns of thought and emotion that interfere with daily life and well-being.

Defining Anorexia: Beyond the Stereotypes

To understand why anorexia is a mental health disorder, one must first define what anorexia truly entails. Clinically, anorexia nervosa is characterized by restricted food intake leading to significantly low body weight, an overwhelming fear of weight gain, and a distorted perception of one’s own body. Yet this definition only scratches the surface. Underneath the behaviors are deeply ingrained psychological issues, often rooted in trauma, anxiety, perfectionism, and low self-worth.

Contrary to popular belief, anorexia does not only affect young, white, affluent females. It can and does occur across genders, races, socioeconomic statuses, and age groups. The persistence of stereotypes not only stigmatizes those affected but also delays diagnosis and treatment for individuals who do not fit the assumed profile. Recognizing the diversity of those impacted is a key step toward reducing stigma and increasing accessibility to care.

The psychological underpinnings of anorexia are often entangled with other mental health disorders, including depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and generalized anxiety disorder. These co-occurring conditions further highlight why anorexia is a mental disorder rather than merely a lifestyle choice or behavioral quirk. People with anorexia frequently struggle with intrusive thoughts, emotional dysregulation, and compulsive behaviors, all of which align with characteristics of other recognized psychological conditions.

The Psychological Mechanisms Driving Anorexia

At its core, anorexia is a psychological coping mechanism. For many, restrictive eating provides a sense of control in a world that feels unpredictable or overwhelming. This perceived control can be intoxicating, especially for individuals who feel powerless in other areas of their lives. The act of controlling food intake becomes a substitute for emotional regulation, offering a temporary reprieve from anxiety, fear, or despair.

Anorexia is also fueled by cognitive distortions. Individuals often engage in black-and-white thinking, believing that eating a certain food or gaining a small amount of weight equates to failure. These cognitive distortions are not simply bad habits; they are symptoms of a psychological disorder that alter the way a person interprets reality. When we ask, “is anorexia a mental disorder?” we are acknowledging that the roots of the illness lie not just in the body, but in the mind’s processing of thoughts, beliefs, and emotions.

Moreover, individuals with anorexia often experience a disconnect between their self-perception and objective reality. This body image distortion is not a fleeting concern but a deeply embedded belief that can persist even in the face of malnutrition or hospitalization. In this way, anorexia shares characteristics with other mental illnesses that involve delusions or altered self-concept, further underscoring that anorexia is a psychological disorder in every sense.

Neurobiological and Genetic Contributions to Anorexia

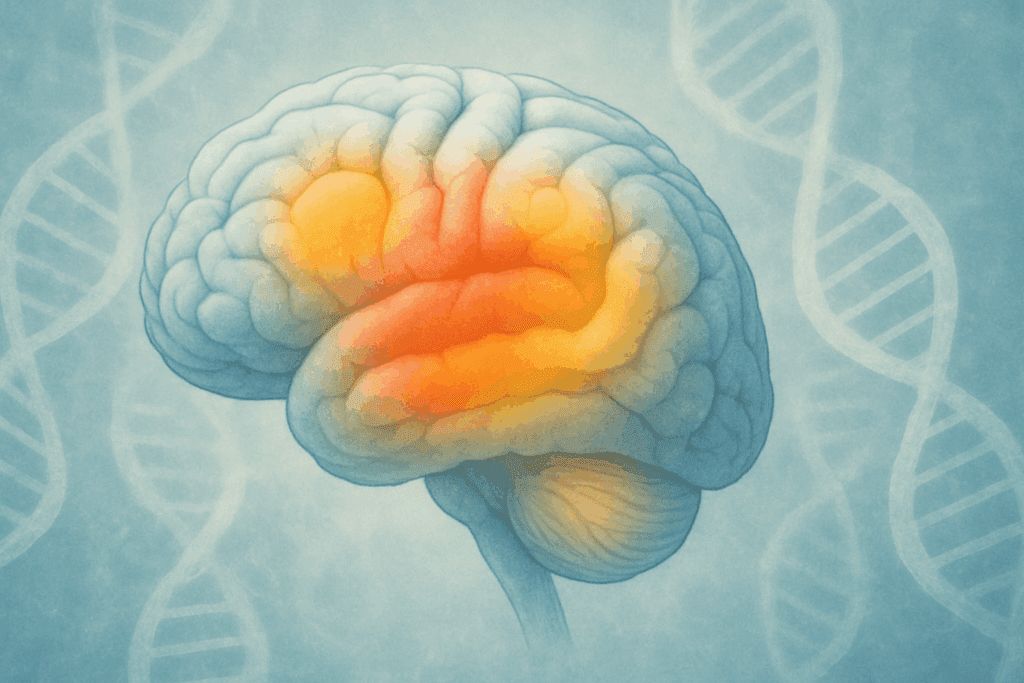

Scientific advancements have deepened our understanding of the biological and genetic components of anorexia, offering further evidence that it is a legitimate mental health disorder. Brain imaging studies have shown abnormalities in areas of the brain associated with reward processing, impulse control, and emotion regulation. These differences may help explain why individuals with anorexia find it so difficult to experience pleasure from food or to interrupt compulsive behaviors.

Research has also identified specific genetic markers that appear to increase the risk for developing anorexia. Twin studies suggest that up to 50-60% of the risk may be hereditary, emphasizing that biology plays a significant role. Importantly, these findings do not diminish the psychological aspects of the illness but rather complement them, highlighting anorexia as a complex interplay of nature and nurture.

Understanding the neurobiological basis of anorexia also has important implications for treatment. By recognizing that anorexia is a mental health disorder with biological roots, we can move away from blaming individuals for their condition and toward developing more targeted, compassionate interventions. This knowledge reinforces that recovery requires more than willpower; it demands medical, psychological, and social support tailored to the individual.

Cultural and Societal Influences on Anorexia

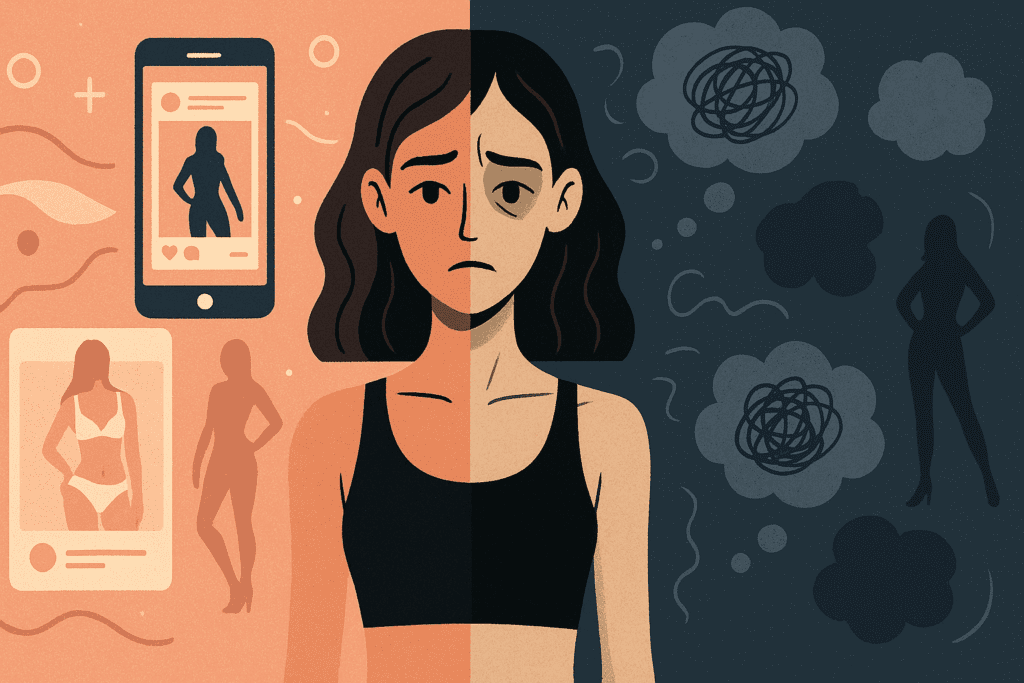

While anorexia has biological and psychological components, it also exists within a cultural context that cannot be ignored. Western societies, in particular, are saturated with messages that equate thinness with success, self-control, and beauty. These ideals are internalized at a young age and reinforced through media, advertising, and even casual conversations.

It is no coincidence that eating disorder rates are higher in societies with strong weight bias and narrow beauty standards. When we discuss eating disorder facts, it’s critical to acknowledge that these disorders do not develop in a vacuum. Social comparison, media influence, and fatphobia all contribute to the onset and maintenance of anorexia. Cultural messages act as triggers, particularly for individuals who are already vulnerable due to genetic or psychological predispositions.

Moreover, societal responses to weight loss often reinforce disordered behaviors. Compliments about weight loss, glorification of extreme fitness regimens, and the moralization of food choices can validate and even encourage anorexic behaviors. These dynamics further illustrate that anorexia is a mental disorder that thrives in a particular sociocultural environment—an environment that must also be addressed in prevention and treatment efforts.

Treatment Approaches: A Multidisciplinary Path to Recovery

Given the complexity of anorexia, treatment requires a multidisciplinary approach that addresses both the physical and psychological dimensions of the disorder. Medical stabilization is often the first step, particularly for individuals who are severely underweight or experiencing life-threatening complications. However, refeeding alone is not sufficient. Without concurrent psychological treatment, physical recovery is likely to be short-lived.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is one of the most evidence-based approaches for treating anorexia. CBT helps individuals identify and challenge distorted thoughts about food, body image, and self-worth. By replacing these thoughts with more balanced perspectives, patients can begin to develop healthier behaviors and coping strategies. This therapeutic process underscores the psychological roots of the disorder and why it is accurate to say that anorexia is a psychological disorder.

Family-based treatment (FBT), particularly for adolescents, has also shown promising outcomes. This approach involves the family in the recovery process, helping them support nutritional rehabilitation and address underlying dynamics that may contribute to the illness. Medications may be used in some cases to manage co-occurring conditions such as depression or anxiety, though there is no specific pharmacological cure for anorexia itself.

Importantly, long-term recovery often involves not only structured therapy but also the development of a supportive community. Group therapy, peer mentoring, and support groups can play an invaluable role in helping individuals feel understood and less alone. These community-based strategies reinforce the idea that healing from anorexia is not merely a physical endeavor but a profound psychological and emotional journey.

The Importance of Early Intervention and Education

One of the most crucial eating disorder facts is that early intervention significantly improves treatment outcomes. The sooner anorexia is recognized and addressed, the better the chances for a full recovery. Unfortunately, delays in diagnosis are common due to stigma, denial, and a lack of awareness among both the public and healthcare professionals.

Education is a powerful tool in combating these barriers. Schools, primary care settings, and media outlets can all play a role in disseminating accurate information about anorexia and other eating disorders. By reinforcing that anorexia is a mental health disorder—and not a choice, phase, or character flaw—we create an environment that encourages help-seeking and reduces shame.

Educational campaigns should also focus on dismantling myths. For example, the misconception that someone must appear emaciated to be struggling with anorexia can be particularly damaging. Many individuals maintain a normal weight while exhibiting severe disordered behaviors and thoughts. This reality underscores the need for diagnostic criteria and public understanding to go beyond physical appearance.

Training for healthcare providers is equally important. Medical professionals must be equipped to recognize the psychological signs of anorexia, especially in populations that do not fit traditional stereotypes. Continuing education on how anorexia is a psychological disorder can lead to more timely referrals and more effective interventions.

Looking Toward Prevention: Promoting a Healthy Relationship with Food and Body

Preventing anorexia and other eating disorders begins with promoting a healthier relationship with food and body image across the lifespan. This involves not only individual efforts but systemic changes in how society treats weight, appearance, and mental health. When children grow up in environments that emphasize body diversity, intuitive eating, and emotional expression, they are less likely to internalize harmful messages that contribute to disordered eating.

Parents, educators, and community leaders can foster resilience by modeling balanced eating behaviors, rejecting diet culture, and encouraging self-compassion. Media literacy programs can also help individuals critically evaluate the unrealistic and often manipulated images they see online and in advertisements. These strategies, while not foolproof, can serve as protective factors against the development of anorexia.

Workplaces and healthcare systems should also play a role in prevention. Employee wellness programs, routine mental health screenings, and inclusive medical practices can all contribute to early detection and intervention. By embedding support within everyday systems, we create more opportunities for individuals to access help before the disorder becomes entrenched.

Recognizing that anorexia is a mental disorder also has implications for public policy. Increased funding for mental health services, better insurance coverage for eating disorder treatment, and legal protections against weight-based discrimination can all support prevention and recovery. These systemic changes are essential for creating a culture in which mental health—including eating disorders—is treated with the seriousness it deserves.

Frequently Asked Questions: Understanding Anorexia as a Mental Health Disorder

What makes anorexia different from simply wanting to lose weight?

Anorexia differs significantly from ordinary dieting or a desire to lose weight. While many people may engage in short-term dieting to improve health or appearance, anorexia involves a deeply ingrained fear of gaining weight and a distorted perception of one’s body that persists despite clear evidence to the contrary. This disconnection from reality is one reason anorexia is a psychological disorder. Individuals with anorexia often continue to restrict food even when they are dangerously underweight and experiencing serious health consequences. These behaviors are not about achieving a goal but about managing overwhelming emotional distress through control, further emphasizing why anorexia is a mental health disorder.

How does anorexia affect a person’s brain function over time?

Long-term anorexia can cause significant changes in brain structure and function. Malnutrition impacts neurotransmitter production, particularly serotonin and dopamine, which are essential for mood regulation, motivation, and reward processing. This imbalance contributes to emotional instability and reinforces obsessive behaviors around food and body image, showing another way anorexia is a mental disorder with both psychological and neurological consequences. Brain imaging studies also reveal a decrease in grey matter volume, which may impair decision-making and emotional insight. Fortunately, some of these changes can improve with sustained recovery and nutritional rehabilitation.

Can someone have anorexia without appearing extremely underweight?

Yes, absolutely. A common myth is that anorexia is only present when someone is visibly emaciated. However, weight is not the sole indicator of this disorder. Many people with atypical anorexia exhibit the same behaviors, thought patterns, and health risks but may remain within or even above the average weight range. These cases often go undetected due to biases in how we define health and appearance, but the psychological impact remains profound. Recognizing that anorexia is a psychological disorder regardless of weight is vital for early intervention and appropriate care.

Why is early intervention so critical in treating anorexia?

The earlier anorexia is diagnosed and treated, the better the prognosis. Chronic malnutrition and long-standing distorted thinking patterns can become deeply entrenched, making recovery more difficult over time. Early intervention also reduces the risk of irreversible damage to organs, bone density, and fertility. By addressing anorexia as a mental health disorder from the outset, clinicians can offer more effective, targeted therapies. Encouraging early help-seeking behaviors also reduces stigma and supports better long-term outcomes, especially among adolescents.

How do social media and modern beauty standards contribute to anorexia?

Social media platforms often glorify unrealistic body ideals and perpetuate diet culture, which can fuel disordered eating behaviors in vulnerable individuals. Constant exposure to edited images and weight-centric content fosters comparison and self-criticism. While these influences alone do not cause anorexia, they can act as powerful environmental triggers in those predisposed to the condition. This intersection of cultural pressure and psychological vulnerability reinforces why anorexia is a mental disorder influenced by both internal and external factors. Promoting media literacy and body positivity are important steps in prevention.

What role do families play in anorexia recovery?

Family involvement is often essential, especially in adolescent cases. Evidence-based approaches like Family-Based Treatment (FBT) empower families to support nutritional rehabilitation and address emotional undercurrents within the home environment. Loved ones can also help challenge distorted thoughts, reinforce healthy behaviors, and provide accountability. However, families must also learn to avoid unintentionally reinforcing harmful patterns or language. When families understand that anorexia is a mental health disorder, they are better equipped to offer the compassionate, structured support needed for recovery.

Is anorexia linked to other mental health conditions?

Yes, anorexia frequently co-occurs with other psychological disorders such as anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). These comorbid conditions may predate the eating disorder or emerge during its progression. Shared features like perfectionism, rumination, and emotional regulation difficulties suggest overlapping neural pathways and vulnerabilities. Understanding these connections reinforces the answer to the question, “is anorexia a mental disorder?” by highlighting its relationship to broader patterns of mental illness. Effective treatment often requires addressing these co-occurring conditions alongside the eating disorder.

Are there any emerging therapies for anorexia beyond traditional talk therapy?

Yes, recent developments in anorexia treatment include novel approaches such as virtual reality (VR) therapy, neurofeedback, and exposure-based interventions aimed at retraining emotional responses to food and body image. These techniques target the brain’s neural circuits and provide experiential tools to challenge fear responses. Nutritional psychiatry, which explores how gut health and diet influence mental well-being, is another emerging field. While these therapies are not replacements for standard care, they represent promising adjuncts, especially when integrated into a comprehensive treatment plan. As our understanding deepens, new methods continue to affirm that anorexia is a psychological disorder requiring innovative, individualized care.

How does the healthcare system sometimes fail those with anorexia?

Despite increased awareness, many healthcare systems still lack adequate training and resources for identifying and treating eating disorders. Misconceptions among professionals—such as assuming someone isn’t ill unless they are underweight—can lead to delayed diagnosis and insufficient care. Additionally, insurance limitations often restrict access to specialized treatment, and disparities in care persist across race, gender, and income. Recognizing that anorexia is a mental health disorder and not a choice or character flaw is critical to improving clinical practices and policies. Systemic changes are needed to ensure timely, equitable, and comprehensive support for all affected individuals.

What does full recovery from anorexia look like?

Full recovery from anorexia is not simply about restoring weight but involves a complete transformation in thought patterns, emotional regulation, and self-perception. Individuals must rebuild trust with their bodies, learn to experience food without fear, and reconnect with their values and relationships. Recovery also means developing new coping mechanisms to manage stress, trauma, or perfectionism without reverting to disordered behaviors. It is a deeply personal and often non-linear journey, but one that is entirely possible with the right support. Understanding that anorexia is a mental disorder helps frame recovery as a process of psychological healing, not just physical restoration.

Final Thoughts: Understanding Why Anorexia Is a Mental Health Disorder Matters for Everyone

At its core, understanding anorexia as a mental health disorder reshapes how we approach the illness—clinically, socially, and personally. Recognizing that anorexia is a psychological disorder with complex biological, emotional, and cultural components allows us to move away from blame and toward empathy. This shift in perspective opens the door to more effective treatments, earlier interventions, and more inclusive support systems.

When we explore eating disorder facts with intellectual honesty and compassion, we uncover the profound suffering that often lies beneath the surface. We also discover the resilience of those who face this disorder and the immense healing potential that exists when treatment is approached holistically. Yes, anorexia is a mental health disorder—and acknowledging this truth is the first step in creating a world where recovery is not only possible but expected.

Whether you are a healthcare provider, educator, loved one, or someone struggling with food and body image, this understanding is vital. It is through informed awareness and collective action that we can challenge stigma, advocate for change, and support the mental wellness of everyone affected by anorexia.

Was this article helpful? Don’t let it stop with you. Share it right now with someone who needs to see it—whether it’s a friend, a colleague, or your whole network. And if staying ahead on this topic matters to you, subscribe to this publication for the most up-to-date information. You’ll get the latest insights delivered straight to you—no searching, no missing out.