Understanding the profound impact of dietary fiber on digestive health has become an essential component of modern wellness conversations. For individuals seeking to improve gut health through holistic means, the nutritional benefits of fiber provide a compelling area of study and application. This article delves deeply into the biological functions, therapeutic potential, and scientifically backed advantages of fiber, framing the discussion within the broader context of gut microbiota, holistic nutrition, and digestive resilience.

You may also like: The Ultimate Guide to Gut Healthy Meals: Best Meals for Gut Health and Nourishing Recipes You’ll Love

What Is Fibre? Exploring the Foundations of Dietary Fiber

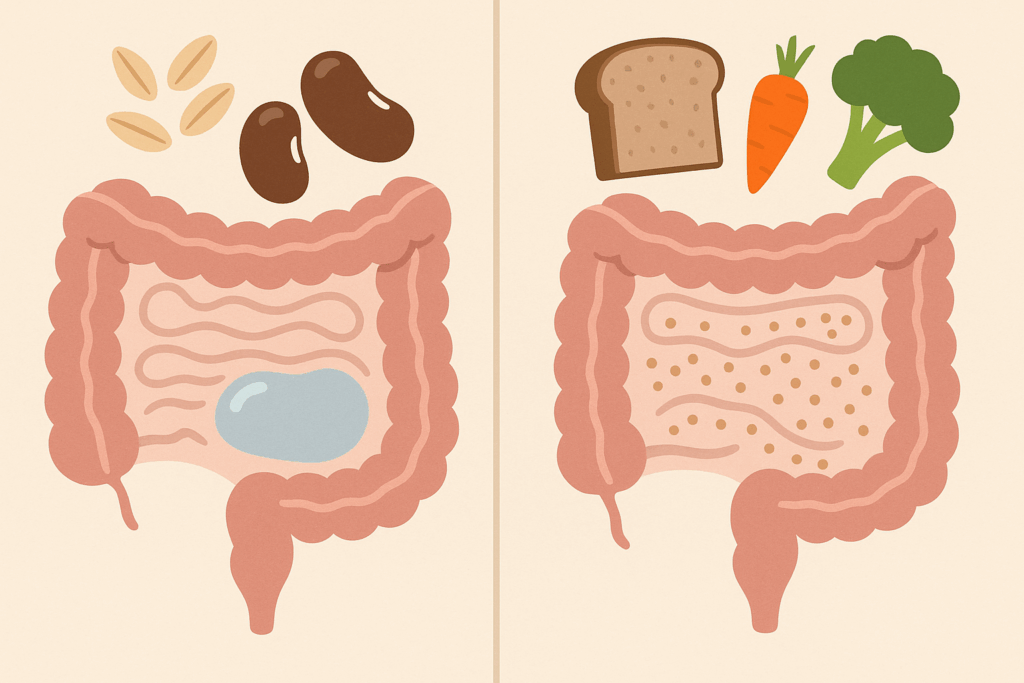

To fully appreciate the fiber health benefits, it is necessary to begin with a clear understanding of what is fibre in the context of nutrition. Fiber, or roughage, refers to the indigestible parts of plant foods that pass relatively intact through the digestive system. While fiber is not absorbed or broken down by digestive enzymes in the small intestine, it plays a critical role in gastrointestinal function, metabolic regulation, and microbial balance. The fiber definition in foods typically includes two main categories: soluble and insoluble fiber. Soluble fiber dissolves in water and forms a gel-like substance, which can help lower blood cholesterol and glucose levels. In contrast, insoluble fiber promotes the movement of material through the digestive system and increases stool bulk, making it particularly beneficial for individuals dealing with constipation or irregular bowel movements.

Understanding Fiber Definition Nutrition and Its Biological Significance

From a biochemical standpoint, the fiber definition nutrition scholars agree upon centers on its non-digestible carbohydrate structure. Unlike starches and sugars, which are broken down for energy, fiber remains largely intact until it reaches the colon, where it is partially fermented by gut bacteria. This fermentation process produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which nourish the colon lining and contribute to systemic anti-inflammatory effects. Therefore, answering the question, “Is fiber considered as a nutrient?” requires an appreciation of its indirect but essential role in maintaining homeostasis. While fiber does not provide calories in the traditional sense, it is increasingly recognized as a vital dietary component that supports immunity, regulates hormones, and enhances overall digestive function.

Where Does Fiber Come From? Identifying Rich Sources of Plant-Based Fiber

To integrate fiber into a diet effectively, it is important to identify where does fiber come from in the culinary landscape. Plant-based foods are the exclusive source of natural dietary fiber. Fruits such as apples, berries, and pears offer both soluble and insoluble fiber, while vegetables like broccoli, Brussels sprouts, and carrots are notable for their high fiber content. Legumes, including lentils, chickpeas, and black beans, provide substantial amounts of fiber, often exceeding the fiber content found in many grains. Whole grains like oats, quinoa, and barley are also celebrated for their fiber-rich profiles, particularly in their unprocessed or minimally processed forms. Incorporating a wide variety of these foods ensures a balanced intake of different fiber types, enhancing the advantages of a high fibre diet in both the short and long term.

The Nutritional Benefits of Fiber: A Core Element of Digestive Wellness

One of the most researched and respected domains in holistic health is the study of the nutritional benefits of fiber. These benefits are multifaceted, encompassing both gastrointestinal and systemic effects. At the most fundamental level, fiber enhances bowel regularity, reducing the risk of constipation and promoting efficient waste elimination. In doing so, it helps to prevent conditions such as diverticulitis, hemorrhoids, and colorectal cancer. Furthermore, fiber plays a crucial role in modulating blood sugar levels by slowing the absorption of glucose, thereby providing stability for individuals managing diabetes or metabolic syndrome.

Another key aspect of the nutritional benefits of fiber is its effect on lipid profiles. Soluble fiber has been shown to lower LDL cholesterol levels, reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease. Moreover, fiber contributes to satiety, which aids in appetite regulation and weight management. In the realm of gut health, fiber functions as a prebiotic, fostering the growth of beneficial bacteria such as Bifidobacteria and Lactobacillus. These microbes produce bioactive compounds that support immune health, mental clarity, and mood balance, making the fiber digestion process central to holistic well-being.

Is Fiber a Nutrient? Reassessing Traditional Nutritional Frameworks

Despite its clear physiological impact, the question “Is fiber a nutrient?” often arises in academic and clinical contexts. Traditionally, nutrients have been classified as substances that provide energy or support bodily structures, such as proteins, fats, and vitamins. However, modern nutrition science increasingly acknowledges fiber as a functional nutrient due to its critical role in maintaining health, even though it does not contribute caloric energy. This reevaluation reflects a broader shift toward understanding nutrition through a functional lens—recognizing the ways in which food components influence biological processes beyond energy production.

Is Dietary Fiber Good for You? Evidence from Clinical Research

Numerous clinical studies support the assertion that dietary fiber is beneficial for health. Individuals who consume high-fiber diets consistently demonstrate lower risks of chronic illnesses, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and certain cancers. Research published in peer-reviewed journals indicates that increasing fiber intake can significantly improve glycemic control, lower inflammation markers, and enhance microbiota diversity. As such, when one asks, “Is dietary fiber good for you?” the evidence is overwhelmingly affirmative. Additionally, high-fiber diets have been linked to improved cognitive function and reduced incidence of depression, further expanding the scope of fiber’s influence on overall wellness.

Fiber Definition in Foods: Practical Applications for Everyday Nutrition

Applying the fiber definition in foods to meal planning involves understanding the specific fiber content of different ingredients. Nutrition labels often list dietary fiber as a subcategory under total carbohydrates, offering insight into how much fiber a particular food provides. For example, a cup of cooked lentils may contain up to 15 grams of fiber, representing nearly half the daily recommended intake for adults. By contrast, highly processed foods, such as white bread or sugary cereals, typically offer minimal fiber content despite their carbohydrate load. Educating consumers on the difference between whole and refined foods is essential to fostering an understanding of how fiber definition nutrition aligns with real-world eating habits.

Exploring the Advantages of a High Fibre Diet for Holistic Health

The advantages of a high fibre diet extend far beyond digestive regularity. Fiber has been linked to improved hormone balance, enhanced detoxification processes, and reduced levels of circulating estrogen in the bloodstream, making it particularly beneficial for women’s health. Moreover, fiber-rich foods are often naturally dense in antioxidants, phytochemicals, and essential micronutrients, providing synergistic effects that support immune resilience and cellular health. For athletes and physically active individuals, fiber helps maintain a steady release of energy by stabilizing blood glucose levels, reducing the risk of energy crashes during exercise or intense activity. These benefits exemplify why fiber is increasingly viewed as a cornerstone of preventive medicine.

The Nutritional Benefits of Fiber in Preventing Gut Dysbiosis

Gut dysbiosis—the imbalance of intestinal microbes—has been implicated in a wide range of chronic diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease, obesity, and autoimmune disorders. The nutritional benefits of fiber in restoring microbial balance are especially significant in this context. Fiber serves as a primary fuel source for beneficial gut bacteria, enabling them to outcompete pathogenic species and produce metabolites that nourish the intestinal lining. Studies have shown that individuals consuming fiber-rich diets exhibit greater microbial diversity, which is a key marker of gut health and immune competence. As such, increasing fiber intake represents a safe, effective, and holistic strategy for addressing dysbiosis and supporting long-term digestive wellness.

Is Fiber Fattening? Debunking a Common Nutrition Myth

A frequent misconception in popular dieting narratives is the idea that fiber contributes to weight gain. The question “Is fiber fattening?” reflects a misunderstanding of how fiber functions metabolically. In reality, fiber is not digested into glucose and thus does not contribute to caloric energy in the same way as refined carbohydrates. On the contrary, fiber often facilitates weight loss by promoting satiety, reducing overall calorie intake, and enhancing insulin sensitivity. Furthermore, because fiber slows gastric emptying, it helps maintain a sense of fullness over a longer period, which can reduce the frequency and volume of meals. These effects collectively support healthy weight management, making fiber a critical element of any evidence-based dietary plan.

Sentence for Fiber in Nutrition: Educational Approaches for Broader Understanding

In educational and clinical settings, crafting a sentence for fiber in nutrition that encapsulates its importance can aid in promoting public awareness. A concise and effective example might be: “Fiber is an essential component of plant-based foods that supports digestion, balances blood sugar, and feeds beneficial gut bacteria.” Such statements help distill complex scientific information into accessible knowledge for diverse audiences. Teaching the benefits of fiber from early education through adult health programs ensures that individuals have the tools to make informed dietary choices that support their long-term wellness.

The Nutritional Benefits of Fiber Across the Human Lifespan

The nutritional benefits of fiber are not confined to any single life stage; rather, they provide support across the human lifespan. In childhood, fiber contributes to healthy bowel function and may reduce the risk of childhood obesity. For adolescents, it helps regulate hormones during puberty and supports mood stability. In adulthood, fiber plays a preventive role against chronic diseases, while in older age, it assists in maintaining bowel regularity, preventing constipation, and preserving cognitive function. The consistency of these benefits across age groups reinforces the universal value of dietary fiber as part of a lifelong health strategy.

Is Fiber Considered as a Nutrient in Public Health Policy?

The role of fiber in public health has evolved significantly in recent decades. While fiber was once treated as an optional dietary component, many national and international health organizations now include it as a critical element in dietary guidelines. This shift prompts the question: “Is fiber considered as a nutrient by policymakers and public health experts?” Increasingly, the answer is yes. Organizations such as the World Health Organization, the USDA, and the European Food Safety Authority have recognized fiber’s role in disease prevention and quality of life. Government-backed initiatives to increase whole food consumption, improve food labeling, and educate populations on fiber benefits reflect this evolving recognition.

Benefits of Fiber in Diet for Mental and Emotional Wellness

Emerging research in the field of nutritional psychiatry suggests that the benefits of fiber in diet extend to mental and emotional wellness. The gut-brain axis—a bidirectional communication network between the gastrointestinal tract and the brain—is heavily influenced by microbial metabolites produced during fiber fermentation. These compounds, including butyrate and other short-chain fatty acids, have been shown to reduce neuroinflammation, improve mood, and enhance cognitive performance. Individuals consuming high-fiber diets report lower levels of anxiety, depression, and brain fog, especially when paired with probiotic-rich foods. This promising area of study underscores the importance of fiber not only for physical health but also for psychological resilience.

The Nutritional Benefits of Fiber in Disease Prevention and Longevity

Preventive medicine increasingly emphasizes dietary patterns as key determinants of health outcomes and lifespan. The nutritional benefits of fiber are central to this approach, given their association with reduced mortality from cardiovascular disease, cancer, and metabolic disorders. Longitudinal studies following large cohorts over decades have consistently found that individuals with the highest fiber intake experience the lowest rates of disease and premature death. These outcomes are attributed to fiber’s anti-inflammatory properties, glycemic control, and ability to modulate lipid levels. In addition to extending life expectancy, high-fiber diets are associated with higher quality of life, as they support energy, digestive comfort, and mental clarity well into old age.

Frequently Asked Questions: Nutritional Benefits of Fiber for Gut Health and Digestion

How Do the Nutritional Benefits of Fiber Extend Beyond Digestion?

While fiber is most commonly associated with improved digestion, its impact stretches far beyond gastrointestinal health. For instance, fiber plays a crucial role in hormone regulation by binding to excess estrogen and promoting its excretion, which may reduce the risk of hormone-sensitive cancers. Some studies also suggest that a fiber-rich diet can influence gene expression related to inflammation and oxidative stress, supporting cellular resilience. Additionally, fiber helps modulate the absorption of certain minerals, including calcium and magnesium, which are essential for bone health. These findings reinforce the broader nutritional benefits of fiber, emphasizing its systemic contributions to wellness that extend well beyond the gut.

What Is the Connection Between Fiber Digestion and Mental Health?

Fiber digestion significantly affects mental health due to its role in shaping the gut microbiome, which communicates with the brain via the gut-brain axis. Short-chain fatty acids produced during fermentation of dietary fiber influence neurotransmitter production, such as serotonin and GABA. Emerging evidence shows that individuals with higher fiber intake often report lower levels of anxiety and depression, especially when consuming diverse fiber sources. This connection highlights how fiber benefits include emotional regulation and psychological resilience, adding another dimension to the advantages of a high fibre diet. Though more research is needed, early findings underscore fiber’s unique contribution to mental well-being.

How Can Travelers Maintain Fiber Intake While on the Go?

Maintaining a high-fiber diet during travel can be challenging, but it’s entirely possible with planning. Portable foods like dried fruits, roasted chickpeas, and fiber-rich snack bars made from oats and chia seeds can bridge the gap. Ordering meals with whole grains and vegetables whenever available is another effective strategy. Travelers often miss out on fiber due to reliance on processed, convenience foods, which tend to lack sufficient roughage. Recognizing the fiber definition in foods and choosing options accordingly ensures that the fiber health benefits continue, even in transit.

Are There Social or Cultural Barriers That Impact Fiber Consumption?

Yes, cultural perceptions and socioeconomic factors can influence fiber intake across populations. In some cultures, refined white rice or bread is preferred over whole grains, diminishing fiber consumption despite high carbohydrate intake. Economic barriers may also limit access to fresh produce and legumes, which are primary sources of dietary fiber. Social trends like low-carb or keto diets may inadvertently discourage fiber intake, even though such diets often overlook the fiber definition nutrition emphasizes. Addressing these barriers requires culturally sensitive public health messaging and accessible education about the benefits of fiber in diet.

Can a High-Fiber Diet Impact Sleep Quality or Energy Levels?

Surprisingly, the advantages of a high fibre diet can influence sleep and daytime alertness. Stable blood sugar levels, a byproduct of fiber’s slow digestion rate, prevent nighttime energy crashes and can improve sleep continuity. Additionally, the gut microbiome plays a role in melatonin synthesis, and since fiber supports microbial diversity, it indirectly promotes sleep regulation. People consuming high-fiber breakfasts often experience fewer midday energy slumps compared to those eating refined carbohydrates. Thus, when evaluating fiber benefits, it’s worth considering how they support consistent energy and restful sleep.

How Can We Better Understand the Fiber Definition in Foods for Effective Meal Planning?

Understanding the fiber definition in foods is crucial for constructing a gut-supportive meal plan. Beyond just recognizing whole grains and vegetables, it’s important to distinguish between foods with naturally occurring fiber and those with added, synthetic fiber. Ingredients like inulin and polydextrose are often added to processed foods but may not offer the same health effects as fiber from whole foods. Consumers should be encouraged to read nutrition labels carefully and learn which ingredients contribute to genuine fiber health benefits. Effective planning involves selecting whole plant foods that reflect the complete fiber profile rather than relying on fortified products.

Are There Populations Who May Not Tolerate High Fiber Well?

Yes, individuals with certain digestive conditions, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or Crohn’s disease, may find that high-fiber diets exacerbate symptoms. In such cases, the type of fiber becomes more important than the total amount. Low-FODMAP vegetables and soluble fiber sources are often better tolerated than high-insoluble fiber foods like raw cabbage or bran. Understanding the nuanced fiber definition nutrition provides helps tailor interventions for sensitive populations. In these cases, gradual introduction and clinical guidance ensure fiber is used therapeutically rather than problematically.

Why Is There Confusion About Whether Fiber Is Fattening?

The misconception that fiber is fattening likely arises from misunderstanding its bulking effect and association with carbohydrates. In truth, fiber is not absorbed for caloric energy in the traditional sense, and it actually helps regulate appetite and reduce total caloric intake. The term “is fiber fattening” misrepresents the metabolic role fiber plays, as fiber enhances satiety and delays hunger signals. Furthermore, individuals following high-fiber diets tend to have healthier body weights and lower visceral fat levels. Clarifying this helps dismantle a major barrier to fiber adoption, especially among those trying to manage weight.

How Can Educators Use a Sentence for Fiber in Nutrition to Promote Understanding?

Educators can use a well-crafted sentence for fiber in nutrition to distill its benefits into memorable messages. For instance: “Fiber is a plant-based nutrient that feeds your gut microbes, balances blood sugar, and keeps your digestion running smoothly.” Such concise language is powerful in community health initiatives, especially when working with diverse populations. Tailoring the sentence to cultural and linguistic contexts can improve receptivity and adoption. When people can articulate what is fibre and why it matters in simple terms, they’re more likely to make informed dietary choices.

Exploring the Nutritional Benefits of Fiber in Preventing Future Disease

One of the lesser-discussed nutritional benefits of fiber lies in its potential to alter long-term disease risk trajectories. For example, fiber may reduce the bioavailability of carcinogens in the colon by speeding up transit time and improving stool consistency. Additionally, recent studies suggest that fiber can modulate immune checkpoints, potentially reducing autoimmune flare-ups in genetically predisposed individuals. In cardiovascular medicine, fiber has been shown to influence lipid oxidation pathways, reducing arterial plaque buildup. These advanced mechanisms highlight why fiber is increasingly viewed as a preventive tool in integrative and functional medicine circles. As such, fiber digestion is not just about immediate relief but long-term disease prevention and systemic optimization.

Conclusion: Embracing the Nutritional Power of Fiber for Lifelong Gut Health

In conclusion, the powerful nutritional benefits of fiber offer a compelling case for integrating more fiber-rich foods into daily life. From its role in supporting digestive regularity and microbial diversity to its impact on cardiovascular, hormonal, and emotional health, fiber stands out as a cornerstone of holistic nutrition. Whether framed through the lens of scientific inquiry, clinical application, or cultural tradition, the evidence for fiber’s importance is both robust and expanding. By understanding the fiber definition in foods, educating others with a clear sentence for fiber in nutrition, and addressing misconceptions such as “Is fiber fattening?” or “Is fiber considered as a nutrient?”, individuals and communities can make more informed dietary choices that promote both immediate well-being and long-term vitality. Ultimately, embracing the advantages of a high fibre diet is not simply a matter of health optimization—it is an act of empowerment grounded in science, tradition, and the pursuit of balanced living.

Further Reading:

7 Benefits of Fiber That Should Convince You to Eat Enough of It