The heart, a powerful yet delicate organ, carries the burden of every heartbeat throughout our lives. For individuals facing cardiac conditions like heart failure, cardiomegaly, or coronary artery disease, the idea of returning to exercise can feel daunting—if not dangerous. Yet emerging science paints a different picture: under medical guidance, movement may become a lifeline. This article explores the evidence behind the question: can exercise repair heart damage?—and what it means for patients living with chronic heart disease.

You may also like: Smart Nutrition Choices for a Healthier Lifestyle: What to Know About Whole Grain Rice and Whole Wheat Rice

Can Exercise Truly Help Repair Heart Damage? Understanding the Science of Cardiac Adaptation

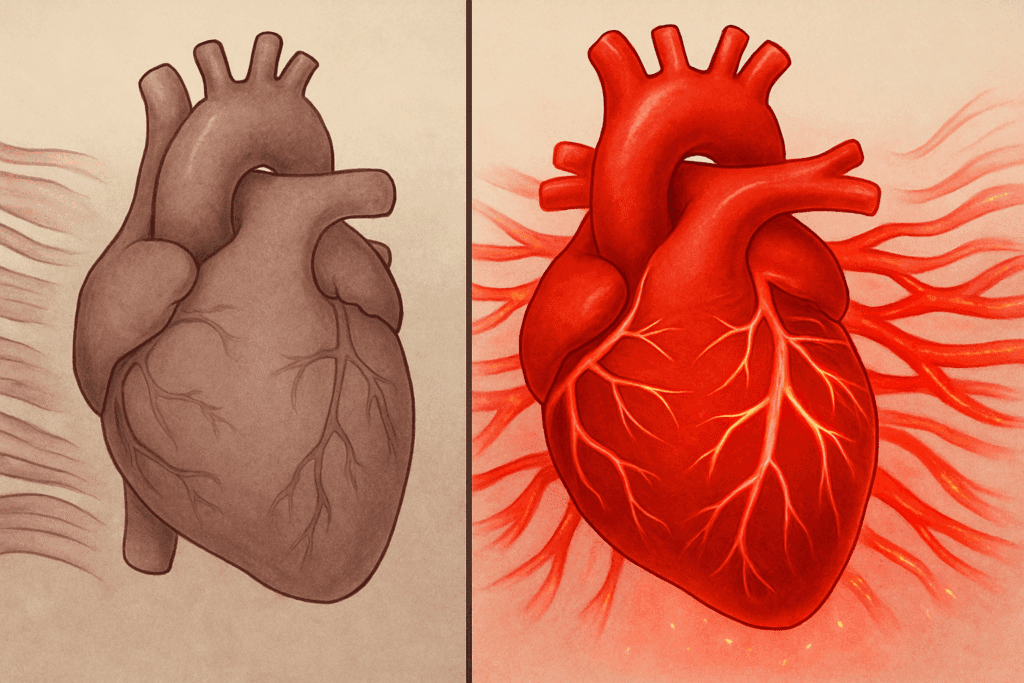

While it may not reverse all forms of structural damage, exercise has a profound impact on heart function. Clinical studies confirm that certain exercises for heart failure can improve cardiac output, enhance circulation, and stimulate positive remodeling of heart tissue. Aerobic activity, in particular, has demonstrated remarkable effects in promoting vascular health and reducing strain on a weakened heart.

It’s important to distinguish between complete tissue regeneration and functional recovery. While exercise cannot regrow dead myocardial cells, it does improve how the remaining heart muscle performs. Through a process known as cardiac remodeling, aerobic training helps the heart adapt to its limitations. Over time, the heart becomes more efficient, enabling patients to engage in daily activities with less fatigue and breathlessness.

Moreover, aerobic training may help prevent future heart attacks by reducing inflammation, improving cholesterol profiles, and enhancing endothelial function. These physiological adaptations mean that regular, low-to-moderate-intensity movement is not just safe—it’s medicinal. With proper oversight, individuals with heart conditions can regain strength, endurance, and confidence in their bodies.

Exercise and Congestive Heart Failure: A Safe Path to Stronger Living

For those living with congestive heart failure (CHF), the prospect of physical exertion can feel overwhelming. Symptoms like fatigue, shortness of breath, and swelling make even basic movements challenging. However, exercises for congestive heart failure, when introduced gradually and safely, have proven to offer both functional and emotional benefits.

Programs tailored around the best exercise for CHF typically begin with low-impact aerobic movements. These may include walking, swimming, stationary cycling, or even chair-based exercises. The goal is to gently condition the body without overtaxing the heart. Over time, even small increases in activity can result in better oxygen use, improved stamina, and fewer hospitalizations.

It’s essential to emphasize personalization. Each case of CHF is different, and any heart condition exercise must reflect individual limitations, medications, and cardiac output levels. With clinical supervision—often via cardiac rehabilitation programs—patients can learn how to monitor heart rate, manage symptoms, and progress safely. In doing so, they rediscover not only mobility but also autonomy.

Cardiomegaly and Movement: Strengthening an Enlarged Heart Through Gentle Exercise

Cardiomegaly, characterized by an enlarged heart, may seem like a condition that would prohibit any form of strenuous movement. But emerging evidence suggests otherwise. When carefully prescribed, a cardiomegaly exercise plan can improve how the heart functions and reduce associated risks such as arrhythmia and fatigue.

Structured aerobic activity encourages the heart to pump more efficiently, despite its size. Moderate-intensity workouts such as slow treadmill walking or aquatic therapy are ideal starting points. These forms of movement allow for cardiovascular conditioning without undue pressure on the heart’s chambers. Strength training with resistance bands can also be incorporated to maintain muscle mass and functional mobility.

Importantly, exercise improves more than physical endurance—it helps prevent deconditioning, a common issue in patients who avoid activity due to fear. With ongoing guidance, patients with cardiomegaly can safely increase their physical thresholds and enjoy a better quality of life. The key lies in consistency, gradual progression, and clinical support.

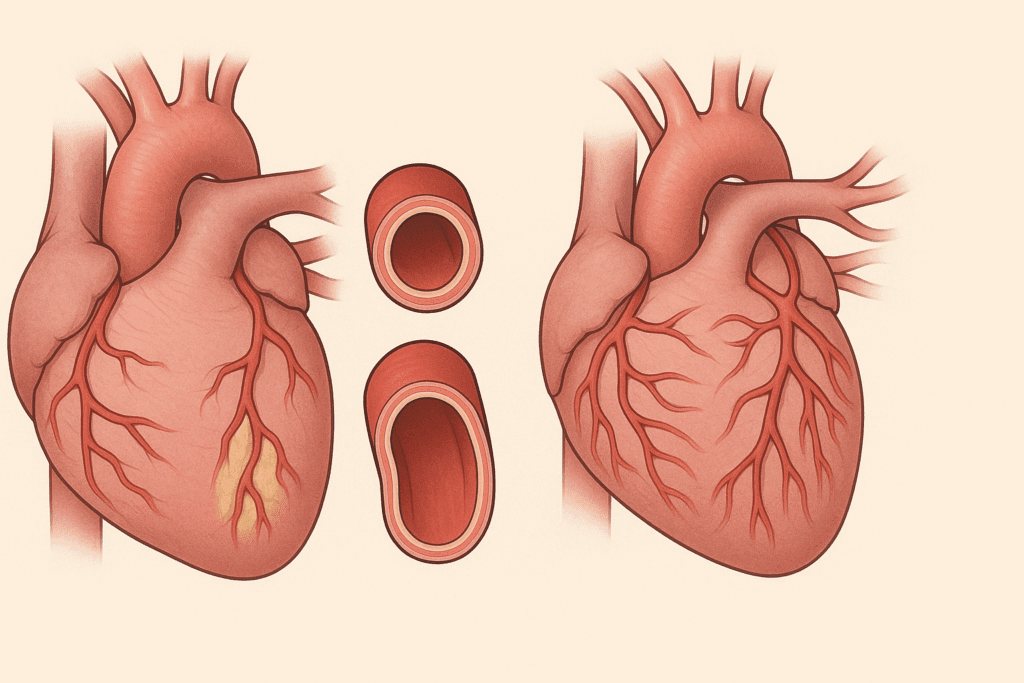

Coronary Artery Disease and Exercise: Preventing Further Damage Through Cardiovascular Training

Among the most common heart conditions, coronary artery disease (CAD) significantly raises the risk of heart attack and stroke. But for patients with CAD, movement isn’t just permissible—it’s protective. The relationship between coronary artery disease and exercise has been extensively studied, with consistent findings showing improvement in lipid levels, blood pressure, and blood vessel function.

Physical activity promotes better oxygenation of the heart muscle and helps open alternate pathways for blood flow, known as collateral circulation. This makes the heart more resilient even if major arteries remain partially blocked. Walking, cycling, or light jogging under supervision has become a mainstay of cardiac rehabilitation for patients recovering from events like angioplasty or bypass surgery.

The takeaway is clear: for those with CAD, heart condition exercise is not a risk to be avoided but a therapy to be embraced—provided it’s properly managed. Even those with advanced disease stages can benefit from light aerobic sessions that improve overall metabolic health and decrease long-term complications.

Can a Weak Heart Be Strengthened? The Promise of Progressive Cardiac Conditioning

Patients with diminished heart function often wonder: can a weak heart be strengthened? Modern cardiology answers with cautious optimism. The heart, although limited in regenerative capacity, is capable of improving its function through well-calibrated conditioning programs. This means that even those with a reduced ejection fraction can benefit from structured fitness routines.

The answer lies in progressive overload—the gradual increase of physical demand on the body. In heart failure patients, this might involve interval walking, where brief periods of slow walking alternate with slightly brisker paces. These small fluctuations challenge the cardiovascular system while remaining within safe parameters. As strength builds, so does endurance, oxygen delivery, and even psychological resilience.

These improvements are not theoretical. Clinical trials consistently show that regular exercise in heart failure patients increases cardiac efficiency and reduces hospitalization. Furthermore, strengthening surrounding muscles decreases the load on the heart, helping it perform better with less effort. In short, the answer to whether a weak heart can be strengthened is yes—with patience, precision, and perseverance.

The Emotional and Psychological Healing Power of Movement

Beyond physiological recovery, exercise has profound emotional and psychological benefits for heart patients. Depression and anxiety are common in individuals diagnosed with CHF, CAD, or cardiomegaly. Engaging in routine physical activity—especially in group-based cardiac rehab settings—offers social connection, confidence-building, and emotional support.

The structured nature of exercise restores a sense of control for many patients who feel helpless in the face of illness. Small wins, like walking for an extra five minutes or climbing stairs without gasping, can be transformative. They remind patients that progress is possible and that their efforts are worthwhile. Moreover, exercise reduces stress hormone levels and boosts the production of endorphins, naturally elevating mood.

Mind-body practices like yoga and tai chi are particularly effective for combining movement with mindfulness. When adapted for cardiac safety, they provide balance training, flexibility, and stress relief. These gentle routines are especially valuable for older patients or those beginning their journey to recovery. Over time, they become not just tools for fitness—but pathways to joy, purpose, and inner peace.

Building a Safe and Sustainable Cardiac Exercise Plan

Creating a personalized exercise plan is crucial for long-term success in heart recovery. This begins with an in-depth health assessment that considers the patient’s medical history, medications, baseline fitness, and personal goals. From there, a multidisciplinary care team—including cardiologists, physical therapists, and exercise physiologists—can design a safe starting point.

The most effective programs include a combination of aerobic activity, resistance training, and flexibility work. For CHF patients, the best exercise for congestive heart failure often involves interval-based aerobic movement and light strength work. Flexibility and balance training help prevent falls and maintain daily function. Wearable fitness trackers offer real-time insights into heart rate, step count, and energy expenditure—allowing for more responsive adjustments to the routine.

Patients must also be educated on warning signs, such as chest pain, extreme fatigue, or dizziness, that may indicate overexertion. Equipping individuals with the knowledge to listen to their bodies builds confidence and reduces the likelihood of setbacks. Over time, exercise evolves from a prescribed treatment into a sustainable lifestyle

Frequently Asked Questions: Exercise and Heart Health

1. How can exercise support long-term recovery from congestive heart failure?

Long-term recovery from congestive heart failure requires more than medication—it involves lifestyle changes that prioritize consistent, low-impact physical activity. When strategically introduced, exercises for congestive heart failure help improve circulation, reduce fluid retention, and enhance metabolic function over time. These workouts also condition peripheral muscles to be more efficient, allowing the heart to conserve energy during physical tasks. An often-overlooked aspect is the role of exercise in slowing heart muscle deterioration, particularly when paired with optimal medication. By developing a structured and sustainable routine, patients can manage symptoms more effectively while reducing the risk of complications.

2. Can exercise repair heart damage caused by previous heart attacks?

While exercise cannot regenerate scarred heart tissue from past myocardial infarctions, it can initiate vascular adaptations that offset the impact of the damage. The concept behind “can exercise repair heart damage” rests in its ability to improve oxygen delivery and redistribute blood flow via collateral circulation. These physiological adjustments allow the healthy portions of the heart to function more efficiently, compensating for the damaged areas. Moreover, regular exercise improves mitochondrial density and cardiac output, meaning the heart pumps more effectively despite previous injury. In the long term, this results in better symptom control and lower mortality rates among those recovering from heart attacks.

3. What role does strength training play in heart condition exercise routines?

Strength training has increasingly become a valuable component of heart condition exercise programs, once considered risky for cardiac patients. Light to moderate resistance exercises help maintain muscle mass, improve balance, and reduce insulin resistance—factors especially beneficial for older adults with comorbidities. When incorporated safely, strength training complements aerobic routines by lowering blood pressure and enhancing vascular health. For patients with limitations on high-impact cardio, resistance training provides an alternative way to support circulation and functional capacity. A comprehensive fitness plan for heart patients often combines both modalities, maximizing heart and skeletal muscle benefits.

4. How does coronary artery disease influence exercise limitations, and what adaptations are recommended?

In patients with coronary artery disease, exercise capacity is often reduced due to narrowed vessels and decreased blood flow. However, coronary artery disease and exercise can still coexist safely with careful planning and regular evaluation. Individuals should avoid high-intensity activities without physician clearance, opting instead for steady-state cardio like treadmill walking or recumbent cycling. Using a heart rate monitor helps maintain training within safe limits, minimizing the risk of angina or arrhythmias. Over time, these controlled sessions lead to improved endothelial function and vascular elasticity, reducing the likelihood of ischemic episodes.

5. Are there specific types of exercises for heart failure patients who also have diabetes?

For patients with both heart failure and diabetes, tailored movement programs must balance cardiac safety with glucose control. Effective exercises for heart failure in this group include rhythmic, repetitive activities such as walking, elliptical training, or water aerobics—done at moderate intensity. These activities enhance insulin sensitivity and lower A1C levels while supporting cardiac efficiency. It’s important for patients to monitor their blood sugar levels before and after workouts, as exercise can dramatically influence glycemic response. Combining aerobic movement with brief, low-resistance strength work may also improve metabolic health without overburdening the cardiovascular system.

6. What is considered the best exercise for congestive heart failure in older adults?

The best exercise for congestive heart failure in seniors is one that respects both physical limitations and cardiovascular demands. Chair aerobics, gentle tai chi, and short-distance interval walking are commonly recommended for older adults who may struggle with joint issues or poor balance. These activities not only stimulate the heart but also enhance coordination and reduce the risk of falls. Importantly, any best exercise for CHF plan should be initiated under clinical supervision, especially during the first few months. Over time, progression can include light resistance work and short-duration cycling, provided it is tolerated well.

7. Can a weak heart be strengthened through virtual or home-based programs?

Yes, with proper planning and oversight, virtual platforms and home-based interventions offer a feasible pathway for improving cardiac function. The premise that a weak heart can be strengthened doesn’t rely solely on gym access—it depends on adherence, safety education, and consistency. Home-based cardiac rehab models have been validated in clinical trials, showing similar benefits to in-person programs in terms of blood pressure control, exercise tolerance, and psychological outcomes. These models often include live-streamed exercise sessions, app-guided tracking tools, and remote heart rate monitoring. For patients in rural areas or with mobility limitations, virtual care provides a vital opportunity for rehabilitation.

8. What makes cardiomegaly exercise unique compared to other cardiac fitness plans?

Cardiomegaly exercise routines must address the increased risk of heart failure symptoms and arrhythmias caused by an enlarged heart. Unlike standard cardiac rehab programs, these plans emphasize strict intensity control and rest intervals to avoid excessive strain. Techniques such as interval walking and aquatic therapy are favored due to their low impact on systemic blood pressure. Additionally, postural transitions should be managed carefully, as orthostatic hypotension is more common in this group. Customized programming with real-time feedback becomes essential, especially during the initial stages of physical conditioning.

9. How does exercise prevent future heart attacks in high-risk individuals?

For those at high risk, aerobic training may help prevent future heart attacks by promoting collateral vessel development, lowering LDL cholesterol, and improving cardiac autonomic balance. It also enhances nitric oxide production, which supports vasodilation and reduces arterial stiffness. Exercise decreases systemic inflammation—one of the key contributors to atherosclerosis progression. Over time, this lowers the plaque burden and stabilizes existing lesions, making them less prone to rupture. Even for those with previous cardiac events, structured aerobic routines play a central role in secondary prevention strategies.

10. In what ways does exercise enhance heart failure treatment beyond medication?

Understanding how exercise improves heart failure requires looking beyond the mechanics of cardiac output. Physical activity boosts neurohormonal balance, reducing harmful compensatory mechanisms like excess adrenaline or renin-angiotensin activation. It also promotes better kidney function, aiding in fluid management, which is critical for reducing hospitalization. Additionally, exercise improves respiratory muscle strength, helping patients breathe easier during activity and rest. Perhaps most importantly, it fosters patient empowerment, encouraging lifestyle adherence and long-term self-care—factors that pharmacological treatments alone cannot fully address.

Conclusion: Can Exercise Repair Heart Damage? A Resounding Yes—With the Right Approach

While exercise may not restore every damaged cell, it undeniably improves how the heart functions, heals, and adapts. The question can exercise repair heart damage? finds its answer not in absolute reversal, but in meaningful, measurable improvement. For those living with congestive heart failure, cardiomegaly, or coronary artery disease, the path forward isn’t paved with passivity—it’s built on motion, motivation, and medical guidance.

The integration of exercises for heart failure, a personalized cardiomegaly exercise routine, and clinically validated strategies for coronary artery disease and exercise creates a holistic approach to heart health. More importantly, it reaffirms a hopeful truth: a weak heart can be strengthened. And perhaps the most powerful insight of all is that aerobic training may help prevent future heart attacks by improving the heart’s resilience before crisis strikes.

In the end, the best medicine may not come in pill form—it may lie in a daily walk, a slow swim, or a mindful stretch. Movement, when guided and intentional, becomes an act of restoration, one heartbeat at a time.

Further Reading:

Physical Fitness and Risk for Heart Failure and Coronary Artery Disease

Potential Adverse Cardiovascular Effects From Excessive Endurance Exercise

Cardiac Rehabilitation for Patients With Heart Failure: JACC Expert Panel