For many menstruating individuals, the end of a menstrual period is supposed to bring relief—a respite from the bloating, cramping, and mood fluctuations that mark the luteal and menstruation phases. Yet, for some, an unexpected phenomenon occurs: a sudden surge in hunger and an intensifying urge to snack. This experience often prompts the question, “Why do I feel more hungry when coming off my period?” For those trying to stay in tune with their bodies or manage their nutrition mindfully, this pattern can be puzzling and even frustrating. However, there are valid physiological explanations for this uptick in appetite post-period, and understanding them can help normalize the experience rather than pathologize it.

You may also like: How to Stop Emotional Eating and Regain Control: Mindful Nutrition Strategies That Support a Healthier Lifestyle

Appetite fluctuations during the menstrual cycle are not only common but deeply rooted in hormonal shifts. These changes impact a broad range of physiological processes, including metabolism, energy levels, mood, and even the way the brain processes food-related signals. Moreover, cravings—especially those for carbohydrate-rich or sweet foods—often occur both before and after the period. Addressing these post-period food cravings with a combination of biological insight and nutritional strategies allows for more empowered and intuitive eating choices, promoting long-term wellness.

The Hormonal Landscape: What Changes After Your Period Ends?

To understand the appetite surge following menstruation, it helps to explore the hormonal shifts that accompany the menstrual cycle. The cycle is typically divided into four phases: the menstrual, follicular, ovulatory, and luteal phases. Hormones like estrogen and progesterone rise and fall in predictable patterns across these phases, influencing appetite, mood, energy, and cognition.

During menstruation, both estrogen and progesterone levels are at their lowest. This hormonal dip is often associated with fatigue, irritability, and low mood—symptoms that can interfere with appetite. However, as menstruation ends and the follicular phase begins, estrogen levels begin to climb. Estrogen plays a critical role in regulating appetite and is often associated with a decrease in food intake. Yet this doesn’t always mean appetite immediately drops. On the contrary, as energy levels rise and the body begins recovering from the physiological stress of menstruation, hunger often returns with a vengeance.

Additionally, estrogen promotes the production of serotonin, a neurotransmitter that enhances mood and contributes to satiety. When estrogen levels are still relatively low but beginning to rise, serotonin levels might remain low, triggering increased appetite and cravings—particularly for carbohydrate-rich foods, which are known to boost serotonin production. This delicate interplay between hormones and neurotransmitters helps explain why many individuals report increased hunger or specific food cravings before and just after their period.

Replenishing Energy Stores: A Biological Imperative

Menstruation represents a significant expenditure of energy and nutrients. The body undergoes both physical and hormonal stress during this time, which can lead to a temporary deficit in key micronutrients such as iron, magnesium, and B vitamins. These nutrients play vital roles in energy metabolism and overall physiological function. As a result, feeling hungrier after menstruation may be the body’s natural response to replenish depleted energy and nutrient stores.

Iron is particularly critical during and after menstruation due to blood loss. When iron levels drop, the body may increase hunger signals to promote the consumption of iron-rich foods. Similarly, magnesium depletion—which can contribute to fatigue, irritability, and cravings—may lead the brain to seek out nutrient-dense or calorie-dense options. This physiological hunger is not a sign of lack of control or dietary failure, but rather an intelligent biological feedback loop designed to restore balance.

Furthermore, the body’s basal metabolic rate (BMR) can subtly fluctuate during the menstrual cycle, with studies indicating a slight increase in energy expenditure during the luteal and menstrual phases. After this period of increased energy usage, the body may naturally drive hunger as a compensatory mechanism. Feeling more hungry when coming off your period is, in this sense, a natural consequence of biological recovery.

Food Cravings Before and After Your Period: What They Mean and How to Navigate Them

One of the most common concerns related to menstrual-related appetite shifts is the experience of intense food cravings before and after the period. Cravings before menstruation—often referred to as premenstrual cravings—are largely driven by the hormonal decline in estrogen and progesterone. These shifts can alter blood sugar regulation, increase emotional sensitivity, and disrupt serotonin levels, all of which combine to intensify the desire for quick energy sources like sweets and simple carbohydrates.

Post-period cravings, while less often discussed, are just as real and often connected to recovery needs. The types of foods craved can offer clues to the underlying deficiencies or hormonal imbalances. For example, a strong urge for chocolate might signal magnesium depletion, while persistent hunger might reflect a need for more complex carbohydrates, proteins, and healthy fats to rebuild energy reserves. In some cases, cravings for salty foods may be the body’s way of restoring electrolyte balance after the blood and fluid shifts associated with menstruation.

The key to managing food cravings before and after your period lies in a combination of mindfulness, nutritional strategy, and self-compassion. Instead of viewing cravings as something to be eliminated, it’s more beneficial to understand them as signals. Nourishing the body with nutrient-dense, satisfying meals that include lean protein, whole grains, fiber-rich vegetables, and healthy fats can stabilize blood sugar, support mood, and reduce the intensity of cravings.

Psychological and Emotional Factors in Post-Period Hunger

In addition to biological and nutritional explanations, psychological factors also play a significant role in post-period hunger. The relief of having completed the menstrual phase can bring with it a renewed sense of well-being, which may unconsciously trigger more relaxed eating habits. For individuals who restrict food intake or tightly control their diet during their period due to discomfort or low appetite, the post-period rebound may feel like “making up for lost time.”

Moreover, cultural narratives around menstruation and food often shape how individuals interpret their cravings and eating behaviors. There may be guilt or confusion associated with feeling hungrier after menstruation, particularly for those who are trying to maintain a particular eating pattern or body image. This emotional overlay can magnify perceptions of hunger or cause one to misinterpret natural appetite cues as a failure of willpower.

Addressing post-period hunger through a lens of compassion and curiosity can help dismantle these unhelpful patterns. Practicing intuitive eating—a framework that emphasizes body awareness, hunger cues, and emotional neutrality around food—can be particularly beneficial. When we learn to trust our body’s signals and honor our needs without judgment, we create a more harmonious relationship with both food and the menstrual cycle.

Nutritional Strategies to Support Post-Period Recovery and Satiety

Supporting your body nutritionally in the days following menstruation can go a long way in managing increased hunger and preventing nutrient imbalances. Prioritizing iron-rich foods such as lean meats, legumes, tofu, and dark leafy greens can help replenish iron stores. Pairing these with vitamin C-rich foods like citrus, bell peppers, or strawberries can enhance absorption.

Complex carbohydrates like quinoa, brown rice, and oats offer steady energy release and help regulate serotonin production, which may naturally curb post-period cravings. Meanwhile, including healthy fats from sources like avocados, nuts, seeds, and olive oil supports hormone regulation and promotes lasting satiety. Protein-rich foods like eggs, poultry, yogurt, and plant-based options such as lentils and tempeh are essential for tissue repair and overall energy balance.

Hydration is another key consideration. After the fluid retention and potential dehydration experienced during menstruation, replenishing fluids with water, herbal teas, or electrolyte-rich beverages can aid digestion and reduce hunger signals mistaken for thirst. Incorporating magnesium-rich foods like pumpkin seeds, spinach, and dark chocolate can further reduce post-period irritability and stabilize appetite.

Exercise, Energy Balance, and Appetite Regulation Post-Period

The return of physical energy and reduced menstrual symptoms after a period often coincides with a renewed interest in physical activity. Moderate exercise can be a helpful tool in regulating post-period hunger by supporting mood, enhancing metabolic function, and increasing insulin sensitivity. Activities such as walking, yoga, strength training, or dancing can restore energy equilibrium and may also reduce emotional eating triggered by hormonal fluctuations.

However, it is important to recognize that increasing physical activity also raises energy expenditure, which naturally increases appetite. Rather than trying to suppress hunger, it is more effective to support the body with adequate and balanced nutrition. In fact, ignoring hunger cues post-exercise can backfire, leading to overeating or cravings later in the day. Tuning in to how hunger aligns with activity levels can help create a more sustainable and healthful approach to nutrition.

Sleep quality and stress levels also influence hunger regulation. Poor sleep can dysregulate ghrelin and leptin—the hormones that control hunger and fullness—while chronic stress can stimulate cortisol, which is linked to increased appetite and cravings. Prioritizing rest and stress management post-period can therefore help keep appetite in check and reduce the likelihood of emotional eating.

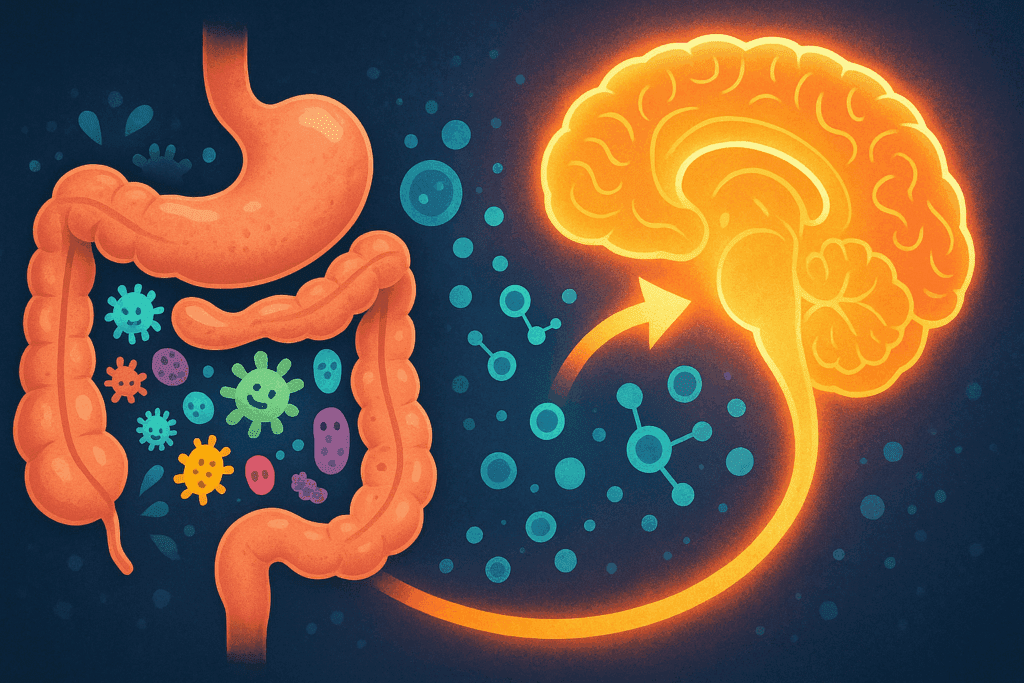

The Role of the Gut-Brain Axis in Post-Menstrual Hunger Signals

Recent research has increasingly highlighted the role of the gut-brain axis in appetite regulation, mood, and hormonal balance. The gut produces a significant amount of serotonin and other neurotransmitters involved in appetite and mood control. Menstrual cycle-related changes in gut function—including bloating, constipation, or altered digestion—may affect how efficiently these signals are transmitted.

After menstruation, gut motility and microbiome balance may begin to normalize, which can impact nutrient absorption and hunger cues. In some cases, post-period hunger may reflect the gut’s adjustment process as it returns to homeostasis. Eating foods that support gut health, such as fermented products like yogurt, kefir, kimchi, and fiber-rich plants, can improve digestion and enhance nutrient bioavailability.

Furthermore, gut bacteria play a role in regulating inflammation, immune function, and even estrogen metabolism. By maintaining a healthy gut environment through diverse, plant-based, fiber-rich diets, individuals may experience more stable moods, reduced cravings, and improved satiety throughout the menstrual cycle.

When to Seek Professional Support for Appetite Fluctuations

While fluctuations in hunger are normal during different phases of the menstrual cycle, excessively intense or distressing symptoms may indicate an underlying condition. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), hypothyroidism, insulin resistance, or disordered eating patterns can all influence hunger regulation and may require medical or nutritional intervention. If increased hunger is accompanied by symptoms like persistent fatigue, dizziness, unexplained weight changes, or mood disturbances, it may be time to consult a healthcare provider.

A registered dietitian or integrative nutritionist can also provide guidance tailored to your individual needs, helping you interpret your body’s signals and develop sustainable dietary strategies. Hormonal health is complex and deeply individualized, and personalized care can make a meaningful difference in both physical well-being and emotional resilience.

Frequently Asked Questions: Understanding Hunger and Cravings Around Your Period

1. Can post-period hunger signal an underlying health imbalance or deficiency?

Yes, feeling more hungry after your period can sometimes reflect deeper nutritional or hormonal imbalances. While it’s normal to wonder, “Why do I feel more hungry when coming off period?”, persistent or extreme appetite shifts might be the body’s way of signaling deficiencies—particularly in iron, magnesium, or B vitamins. For example, significant iron loss during menstruation can lead to fatigue and increased hunger as the body tries to compensate. In some cases, undiagnosed conditions such as thyroid dysfunction, insulin resistance, or PCOS can amplify post-period hunger. If your appetite feels disproportionate or is accompanied by mood swings, dizziness, or extreme fatigue, it’s wise to consult a healthcare provider for further evaluation.

2. Are there psychological factors that intensify food cravings before period and after menstruation?

Absolutely. Emotional and psychological influences play a powerful role in appetite changes. Anticipation of discomfort or stress during the premenstrual phase can subconsciously prime the brain to seek comfort from food. This contributes to heightened food cravings before period onset, particularly for sugar and carbs, which temporarily boost serotonin. After the period ends, some people report a psychological “rebound effect” where the return of energy and relief triggers indulgence or compensatory eating. Understanding the emotional dimension behind the question “Why do I feel more hungry when coming off period?” can help you recognize patterns and create strategies that support mindful eating.

3. Could post-period hunger be affected by how active I am during my cycle?

Yes, your physical activity patterns can significantly influence how your body processes hunger cues throughout your cycle. If you tend to reduce physical activity during menstruation and then resume your usual fitness routine immediately afterward, your energy demands will naturally increase. This shift in energy output can amplify the sensation of being hungrier once your period ends. When asking “Why do I feel more hungry when coming off period?”, it’s important to account for how exercise timing, intensity, and consistency impact metabolic rate and appetite regulation. Aligning your meals with your activity levels can help balance hunger and avoid post-workout cravings.

4. Are food cravings before period more about hormonal signals or learned behavior?

Food cravings before period onset are driven by a blend of biological and psychological mechanisms. Hormones such as progesterone and cortisol rise in the luteal phase, affecting blood sugar and neurotransmitter balance—two major drivers of cravings. However, there’s also a cultural and habitual component. If you’ve repeatedly reached for chocolate or salty snacks in the days before menstruation, your brain may begin to associate this phase with certain “comfort” foods. While addressing cravings requires understanding hormonal triggers, challenging the behavioral routines tied to food cravings before period can reduce their intensity and build more adaptive habits.

5. How does stress impact hunger when transitioning out of menstruation?

Chronic stress has a direct effect on appetite regulation through its impact on cortisol levels. After a period, when the body is trying to regain equilibrium, elevated stress can interfere with the body’s satiety signals. Cortisol increases the desire for high-calorie, high-fat foods and may even disrupt sleep, which in turn influences hunger hormones like ghrelin and leptin. This cascade can exacerbate the feeling of, “Why do I feel more hungry when coming off period?” even if your physical energy needs haven’t increased significantly. Stress-reducing practices like mindfulness, journaling, or gentle movement can be powerful tools in mitigating post-period hunger spikes.

6. Can tracking cravings across several cycles help improve dietary habits?

Tracking your hunger patterns, cravings, and moods across multiple cycles can offer valuable insight into your unique hormonal rhythms. By documenting what you crave and when—especially noting food cravings before period onset and increased hunger afterward—you can begin to anticipate and proactively address your body’s needs. This practice supports more intentional eating, reduces impulsive food choices, and reveals connections between dietary intake, energy levels, and menstrual health. If you’ve ever wondered, “Why do I feel more hungry when coming off period?” journaling can transform that question into a personalized roadmap toward nutritional balance and hormone support.

7. Do cravings after menstruation differ from those experienced beforehand?

Yes, they often differ in both quality and cause. Food cravings before period onset are typically driven by rapid hormone shifts and often lean toward sweets, processed carbs, or comfort foods. Post-menstrual cravings, by contrast, are more likely to reflect nutritional depletion and recovery needs. Many people find they crave iron-rich foods, protein, or even hydration-heavy choices like fruits after their period ends. Recognizing this distinction helps tailor dietary strategies to support each phase—knowing that food cravings before period reflect hormone modulation, while those afterward can be signals of nutrient repletion.

8. Can hydration status influence why I feel more hungry when coming off period?

Hydration plays a surprisingly important role in post-menstrual appetite. After menstruation, the body rebalances fluids that were retained or lost during the cycle. Dehydration—especially if compounded by blood loss—can often be misinterpreted as hunger. This confusion between thirst and appetite is one of the lesser-known answers to the question, “Why do I feel more hungry when coming off period?” Rehydrating with water, electrolyte drinks, or mineral-rich broths can help reduce unnecessary snacking and improve overall well-being. Keeping a water journal or using a hydration reminder app can be helpful tools for cycle-based hydration management.

9. Are there long-term strategies to reduce the intensity of food cravings before period?

Long-term strategies include stabilizing blood sugar, improving gut health, and supporting hormone balance through diet and lifestyle. Regular meals that include complex carbs, protein, and healthy fats can reduce blood sugar fluctuations that exacerbate food cravings before period. In addition, supporting the gut microbiome with fiber, probiotics, and prebiotic foods can enhance serotonin production and reduce inflammation, both of which influence cravings. Lifestyle changes like improved sleep hygiene, reduced caffeine intake, and stress management techniques can also temper the severity of hormonal appetite changes. Over time, these adjustments can make the entire menstrual cycle feel more balanced and predictable.

10. What innovations in menstrual health may change how we approach cycle-related hunger?

Emerging technologies in femtech are revolutionizing how we track and respond to menstrual health. Advanced apps now use AI to predict hunger and energy changes based on hormonal patterns, while at-home hormone testing kits make it easier to identify imbalances. Nutrigenomics is another evolving field, using DNA insights to tailor dietary choices for better hormone regulation. These innovations offer more personalized approaches to understanding why you feel more hungry when coming off period or what drives food cravings before period. As research deepens and tools become more accessible, cycle-aware nutrition may become a foundational element of everyday health planning.

Conclusion: Listening to Your Body and Nourishing It Through the Cycle

Understanding why you feel more hungry when coming off your period involves unraveling the complex interplay between hormones, neurotransmitters, nutritional needs, and emotional states. This heightened hunger is not a flaw or something to be controlled through willpower, but a physiological cue that deserves recognition and respect. By approaching food cravings before and after your period with awareness and curiosity, you can foster a more intuitive and compassionate relationship with your body.

Rather than resisting post-period appetite increases, consider them opportunities to replenish, nourish, and care for yourself. A balanced approach to eating—one that includes iron-rich foods, complex carbohydrates, healthy fats, and mood-supportive nutrients—can make the post-menstrual phase not just tolerable, but regenerative. In this way, mindful eating and nutritional self-awareness become tools not only for physical health but also for emotional empowerment and long-term well-being.

Was this article helpful? Don’t let it stop with you. Share it right now with someone who needs to see it—whether it’s a friend, a colleague, or your whole network. And if staying ahead on this topic matters to you, subscribe to this publication for the most up-to-date information. You’ll get the latest insights delivered straight to you—no searching, no missing out.