Eating disorders remain one of the most complex and misunderstood categories of mental health conditions, touching millions of lives globally. At their core, these disorders—whether anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge-eating disorder, or other specified feeding and eating disorders—are not just about food or weight. Instead, they often stem from a convergence of deep psychological distress, environmental triggers, and biological predispositions. Exploring what is the most significant contributing factor to eating disorders is not merely an academic exercise; it is a critical pursuit that can guide prevention, inform treatment, and potentially save lives. The multifactorial origins of these conditions demand a closer look at the intricate interplay between internal and external forces.

You may also like: How to Stop Emotional Eating and Regain Control: Mindful Nutrition Strategies That Support a Healthier Lifestyle

Unpacking the Psychological Roots of Disordered Eating

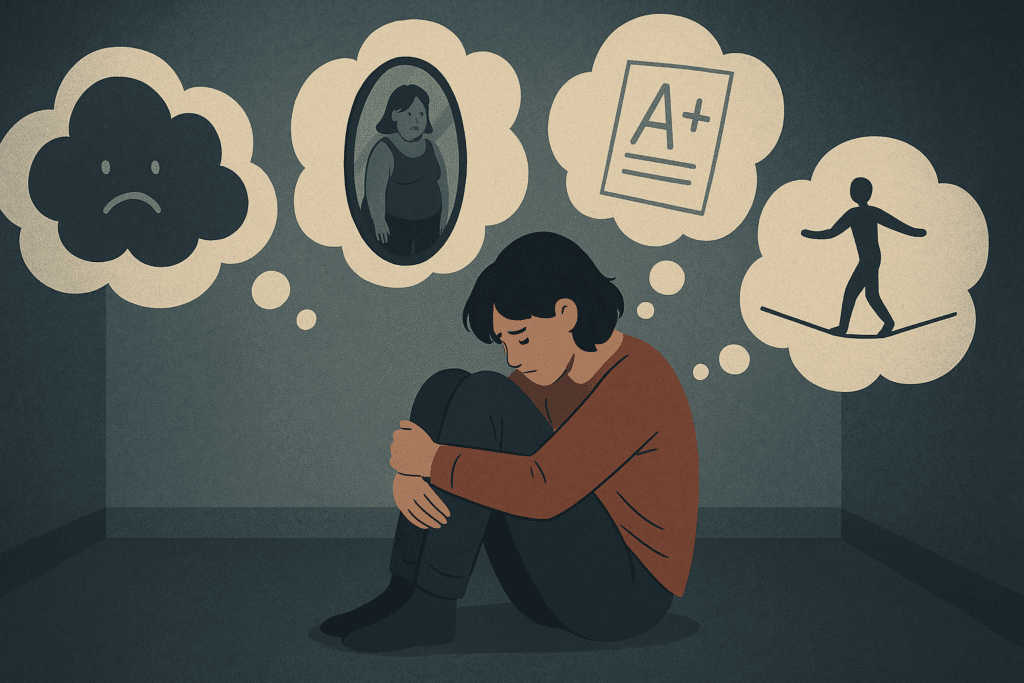

Among the many threads that intertwine in the formation of eating disorders, internal psychological factors frequently emerge as central. For many individuals, these conditions are closely tied to issues of self-worth, perfectionism, control, and emotional regulation. From early childhood experiences to deeply rooted cognitive distortions, internal factors that lead to anorexia and other eating disorders often involve an intense preoccupation with perceived flaws or failures. This obsession can manifest as a drive for thinness, a compulsive need to restrict food intake, or a reliance on bingeing and purging behaviors to cope with stress.

For example, someone who has experienced chronic emotional invalidation may internalize the belief that they are not good enough. This belief, when coupled with perfectionistic tendencies and an inflexible mindset, can fuel behaviors aimed at achieving an unrealistic ideal body image. These internal struggles are often invisible to the outside world, making them especially dangerous. They create a psychological storm in which eating behaviors become a misguided tool for achieving emotional safety or identity control.

Furthermore, depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive tendencies, and trauma histories frequently co-occur with eating disorders, creating a constellation of risk factors. These coexisting mental health issues not only contribute to the development of disordered eating habits but also complicate recovery. Therefore, when considering what is the most significant contributing factor to eating disorders, internal psychological patterns must not be overlooked. These patterns, rooted in how individuals think, feel, and relate to themselves, often provide the fertile ground in which these disorders take root.

Biological Vulnerabilities and Genetic Predispositions

While the psychological landscape offers critical insight, biological and genetic components also carry significant weight in shaping vulnerability. Scientific research increasingly supports the idea that certain individuals are biologically predisposed to develop eating disorders. Studies involving twins, for example, show that anorexia nervosa has a strong heritable component. Genetics can influence personality traits such as impulsivity, anxiety sensitivity, and emotional resilience—all of which play a role in how one responds to environmental stressors and internal distress.

Additionally, abnormalities in neurotransmitter systems, particularly those involving serotonin and dopamine, have been associated with disordered eating behaviors. These neurotransmitters are central to mood regulation, appetite, impulse control, and reward pathways. When these systems are dysregulated, it can affect how individuals experience hunger, satiety, and pleasure—all of which are essential to healthy eating habits. Therefore, internal factors that lead to anorexia may also include neurochemical imbalances that alter one’s emotional and physiological response to food.

Moreover, hormonal fluctuations, particularly during adolescence, can trigger the onset of eating disorders in genetically vulnerable individuals. This insight is essential because it highlights that these conditions are not purely psychological but deeply embedded in the body’s biology. Thus, the question of what is the most significant contributing factor to eating disorders cannot be answered without acknowledging the role of biological vulnerability. This understanding underscores the importance of a holistic treatment approach that integrates medical, nutritional, and psychological support.

Cultural Ideals and Media Messaging

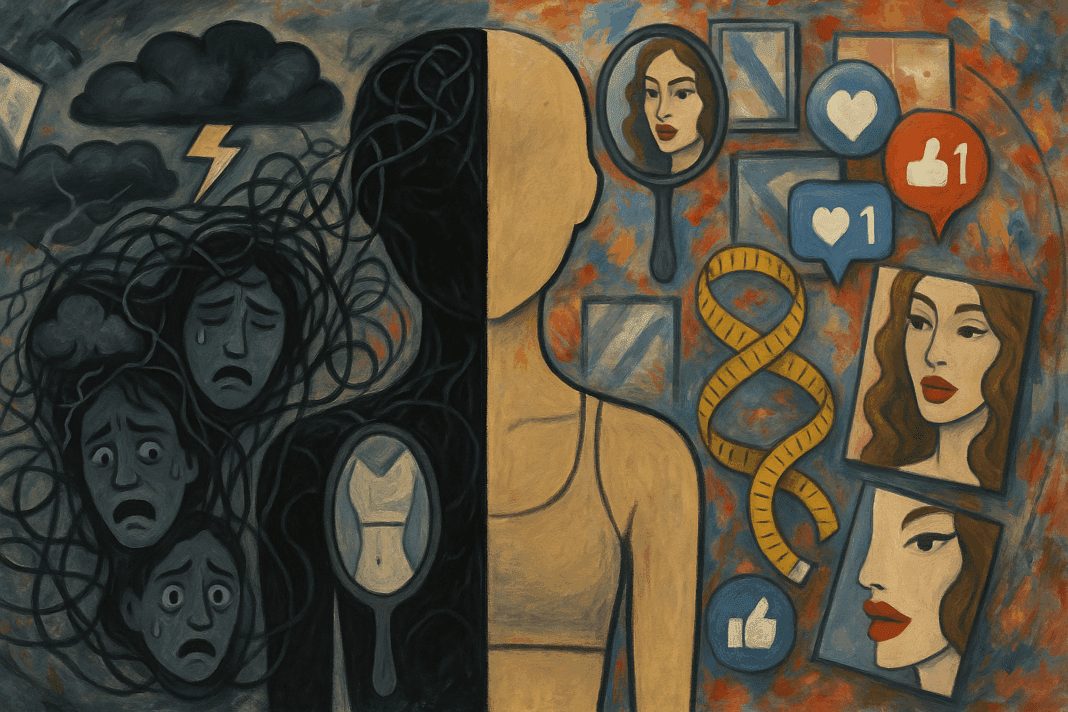

Turning to the external environment, one cannot ignore the powerful influence of societal norms and cultural expectations. The modern media landscape, saturated with images of unattainably thin and digitally altered bodies, sends relentless messages about beauty, success, and worth. For many, particularly adolescents and young adults, these messages can become internalized as standards to strive for, creating an ongoing sense of inadequacy.

External factors that lead to anorexia often stem from this cultural obsession with thinness and physical perfection. Whether through social media, television, fashion magazines, or fitness influencers, individuals are bombarded with cues that equate thin bodies with happiness, desirability, and self-discipline. This distorted value system disproportionately impacts individuals who are already vulnerable due to personality traits or mental health conditions. The constant comparison to idealized images can ignite or exacerbate disordered eating behaviors as individuals attempt to mold their bodies into socially accepted forms.

The pressure does not only come from digital platforms. In many communities and family systems, subtle or overt messages about weight, dieting, and body image are passed down through generations. Comments from parents, peers, or teachers—whether well-meaning or critical—can become deeply embedded in one’s psyche. For example, being praised for weight loss during adolescence may inadvertently reinforce restrictive eating behaviors. These external reinforcements add fuel to the internal conflicts already brewing, contributing further to the development of eating disorders.

Social Dynamics and Peer Influences

Beyond the cultural ideals projected through media, interpersonal relationships also play a critical role. Peer groups, particularly during adolescence, can become hotbeds for comparison, competition, and conformity. In environments where thinness is idolized or where dieting is the norm, individuals may adopt disordered behaviors as a means of social integration or acceptance. These social dynamics are potent external factors that lead to anorexia and other eating disorders.

For instance, in high schools or college settings, diet culture can thrive through seemingly innocuous activities like group dieting, weight-loss challenges, or discussions centered on appearance. Participation in such behaviors can escalate quickly from casual dieting to rigid restriction or compensatory behaviors, especially in those who are already emotionally vulnerable. Peer pressure, even if unintentional, can significantly shape body image perceptions and eating behaviors.

Moreover, the advent of social media has amplified these peer influences exponentially. Platforms that emphasize visuals—such as Instagram, TikTok, or Snapchat—can become echo chambers for body scrutiny, fitness obsession, and harmful comparisons. Algorithms often feed users more of the content they engage with, creating a feedback loop that can be difficult to escape. In this sense, social ecosystems become significant external contributors to the rise of eating disorders.

Family Environment and Early Childhood Experiences

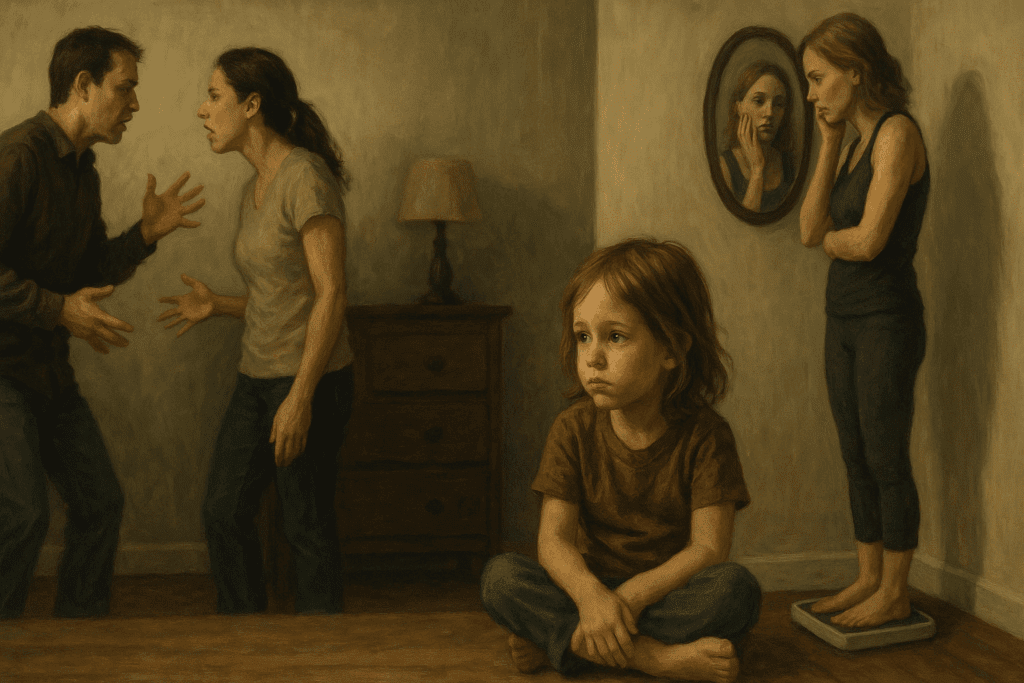

Delving deeper into environmental contributions, the family unit plays a pivotal role in the psychological and emotional development of a child. Early experiences within the home shape one’s self-image, coping mechanisms, and relationship with food. Children who grow up in households where weight is frequently criticized, or where emotional needs are neglected, may develop maladaptive beliefs about their bodies and self-worth. These beliefs can evolve into disordered eating patterns in adolescence or adulthood.

Parents who struggle with their own body image or exhibit disordered eating behaviors may inadvertently model these patterns to their children. Similarly, environments characterized by high conflict, emotional neglect, or lack of attunement can create emotional voids that some children attempt to fill or control through food-related behaviors. When asked what is the most significant contributing factor to eating disorders, clinicians often point to a combination of these familial dynamics, which plant the seeds for later struggles.

Moreover, trauma or attachment disruptions in early childhood can influence the way individuals relate to their bodies. For instance, children who experience sexual abuse, bullying, or parental abandonment often develop body shame or a desire to disappear. Restrictive eating, in such cases, becomes a mechanism for self-protection or dissociation. These complex emotional experiences highlight how both internal and external factors are deeply intertwined, shaping disordered eating in nuanced ways.

Academic and Professional Stressors

Another often overlooked external factor is the pressure to perform academically or professionally. In societies where achievement is highly valued, individuals may internalize the belief that success is the only path to worthiness. This performance-based self-esteem can extend to body image, where thinness becomes another metric of accomplishment.

Young adults navigating competitive academic environments may develop disordered eating as a way to assert control in the face of overwhelming stress. The regimented nature of restrictive eating or obsessive exercise routines can provide a false sense of order and mastery, particularly during times of uncertainty. For high achievers, this behavior often goes unnoticed or is even praised, further entrenching the disorder.

Similarly, in high-stakes professional settings—such as fashion, athletics, or entertainment—the pressure to maintain a certain physique can be relentless. Individuals in these fields are especially vulnerable to developing eating disorders due to constant scrutiny and the perception that appearance directly impacts success. These environments contribute significantly to the external factors that lead to anorexia and related conditions.

The Intersection of Identity, Marginalization, and Disordered Eating

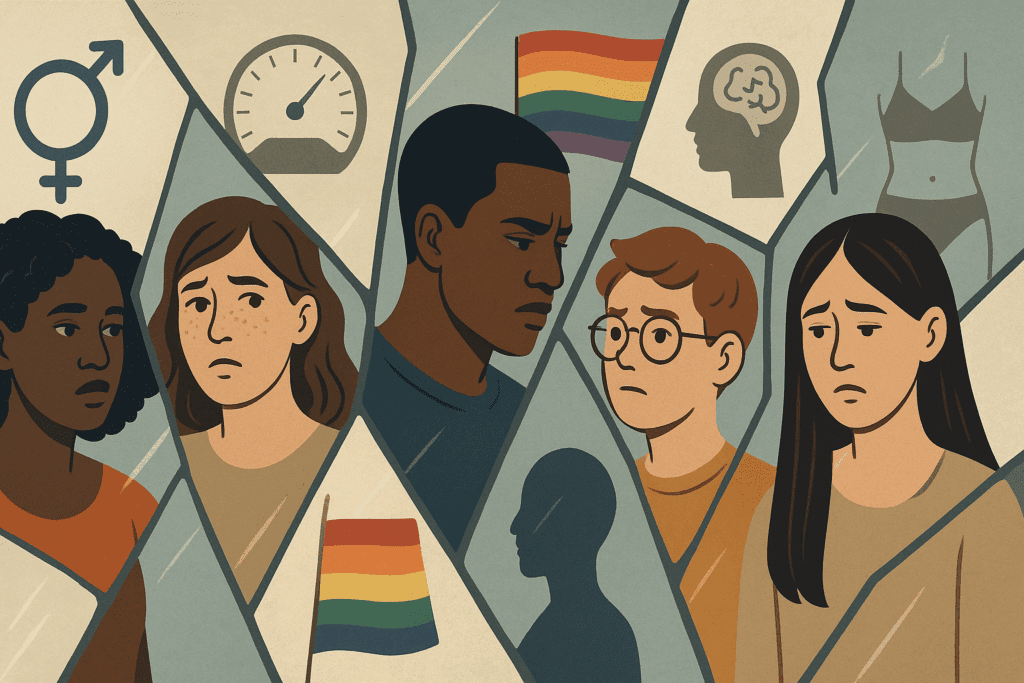

A growing body of research also points to the heightened vulnerability among individuals who identify with marginalized groups. Those who are LGBTQ+, neurodiverse, or part of racial and ethnic minorities often face unique societal pressures that can contribute to the development of eating disorders. For these individuals, body image distress may stem from experiences of exclusion, discrimination, or attempts to conform to dominant cultural norms.

For instance, transgender individuals may engage in disordered eating as a way to align their bodies more closely with their gender identity or to suppress secondary sex characteristics. Similarly, individuals facing racial stereotypes or microaggressions may internalize the belief that they must conform physically to dominant beauty standards in order to be accepted or safe. These are profound external factors that lead to anorexia and other eating disorders, yet they are often overlooked in mainstream discourse.

At the same time, internalized oppression—where individuals absorb negative societal beliefs about their identity—can exacerbate internal conflicts, leading to body dysmorphia and eating pathology. Thus, the intersection of identity and disordered eating requires a nuanced understanding that transcends traditional diagnostic frameworks. Recognizing these intersections is essential to ensuring inclusive, culturally sensitive treatment approaches.

Toward a Holistic Understanding and Effective Intervention

Ultimately, attempting to isolate a singular cause of eating disorders oversimplifies a deeply complex issue. While researchers and clinicians may debate what is the most significant contributing factor to eating disorders, the most accurate answer lies in the dynamic interaction between internal and external influences. Internal factors that lead to anorexia—such as perfectionism, low self-esteem, and emotional dysregulation—often interact with external factors that lead to anorexia, including societal pressures, familial dynamics, and peer influences. This interplay creates a unique vulnerability profile for each individual.

Effective intervention, therefore, requires a multi-pronged approach that addresses both inner psychological wounds and the environmental conditions that sustain disordered eating. Psychotherapeutic modalities like cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), and family-based therapy (FBT) are often necessary components of treatment. Equally important are community support systems, media literacy education, and policy-level efforts to challenge harmful body ideals.

In clinical practice, it is essential to tailor interventions based on the individual’s specific constellation of risk factors. For some, this may mean focusing primarily on trauma resolution and emotional processing. For others, nutritional rehabilitation and behavior regulation may take precedence. Regardless of the pathway, a compassionate, integrative approach remains the gold standard.

Frequently Asked Questions: Understanding Factors That Influence Eating Disorders

What role does emotional intelligence play in eating disorder development and recovery? Emotional intelligence—our ability to identify, understand, and manage our emotions—can have a profound impact on both the development and recovery from eating disorders. Low emotional intelligence may impair one’s ability to process distress in healthy ways, making food restriction or bingeing a substitute for emotional regulation. When evaluating what is the most significant contributing factor to eating disorders, researchers have found that difficulties in recognizing and expressing feelings (also known as alexithymia) are common among individuals with these disorders. In recovery, building emotional awareness through therapy can help individuals develop new coping strategies that don’t revolve around food or body control. While emotional intelligence isn’t often the first factor people consider, it’s an essential piece of the internal puzzle.

Can cultural background influence internal and external factors that lead to anorexia? Yes, cultural background significantly shapes how internal and external factors that lead to anorexia manifest and interact. For instance, in cultures where thinness is not idealized, the pressure to conform to Western beauty standards may still affect individuals through global media. Internally, the stress of navigating conflicting cultural expectations can cause identity-based confusion, which may trigger eating disorder behaviors. In more collectivist cultures, the family’s perception often heavily influences self-worth, adding another layer of complexity to internal factors that lead to anorexia. Understanding what is the most significant contributing factor to eating disorders may differ depending on cultural context, and treatments must be tailored accordingly.

How do perfectionism and achievement orientation affect eating disorder risk? Perfectionism is a well-documented internal factor that contributes to the onset of eating disorders, particularly anorexia nervosa. Individuals who equate personal value with achievement are more likely to fixate on controlling their body as a measurable domain of success. In competitive academic or athletic environments, these tendencies can be exacerbated by external reinforcement of thinness or discipline, acting as potent external factors that lead to anorexia. This interplay between striving for perfection and social approval illustrates how internal and external pressures feed into each other. When asking what is the most significant contributing factor to eating disorders, perfectionistic tendencies frequently rise to the surface in both clinical research and lived experience.

Why do some people develop eating disorders while others exposed to the same influences do not? This divergence often comes down to individual differences in psychological resilience, genetics, and life experiences. Even when two people experience the same external factors that lead to anorexia—such as media pressure or familial dieting habits—their internal responses may vary dramatically. Someone with strong self-esteem and healthy coping strategies may resist these pressures, while someone with underlying anxiety or trauma may internalize them. This highlights the importance of identifying internal factors that lead to anorexia as potential moderators of risk. Ultimately, asking what is the most significant contributing factor to eating disorders reveals that it is the interaction between personal vulnerability and external stressors that determines susceptibility.

Is social media more harmful than traditional media in influencing eating disorder behavior? In many ways, yes. Social media allows for constant, interactive engagement with curated and idealized images, often filtered to emphasize thinness or fitness culture. This continuous exposure acts as a persistent external factor that can erode body satisfaction and normalize disordered behaviors. The added element of peer comparison, particularly through likes, comments, and shared routines, further intensifies the pressure. However, internal factors that lead to anorexia—such as self-critical thought patterns—can make some individuals more sensitive to these messages than others. While traditional media certainly plays a role, the algorithmic nature of social media amplifies what is the most significant contributing factor to eating disorders in real-time and personalized ways.

What is the role of trauma in eating disorder development? Trauma, especially unresolved trauma, is frequently cited as a foundational internal factor in eating disorder development. Survivors of emotional, physical, or sexual abuse may develop disordered eating behaviors as coping mechanisms or forms of self-punishment. For these individuals, food control or body manipulation can create an illusion of safety or numbness. While external factors that lead to anorexia—such as societal beauty standards—may trigger disordered habits, trauma often provides the emotional soil in which these behaviors flourish. Understanding what is the most significant contributing factor to eating disorders in trauma survivors requires a trauma-informed therapeutic lens and specialized care.

Do eating disorders look different in men compared to women? Yes, while eating disorders affect all genders, the way symptoms manifest in men can differ due to cultural expectations around masculinity. Men are often more focused on muscularity than thinness, leading to behaviors like over-exercising or strict protein control rather than calorie restriction alone. These patterns reflect different internal factors that lead to anorexia, often rooted in performance pressure or emotional suppression. External factors that lead to anorexia in men may also include bullying, sports culture, or rigid gender norms. When asking what is the most significant contributing factor to eating disorders in men, it’s essential to avoid gender bias and ensure accurate diagnosis.

How can healthcare providers better assess eating disorder risk in diverse populations? Healthcare providers must go beyond surface-level assessments and understand cultural, socioeconomic, and psychological contexts. Many standard diagnostic tools are based on narrow definitions that fail to capture how internal factors that lead to anorexia may look in people of color, LGBTQ+ individuals, or those with disabilities. Additionally, external factors that lead to anorexia—such as racial discrimination or marginalization—can be easily overlooked if providers aren’t culturally competent. Expanding training in intersectional approaches can improve early detection and reduce disparities in care. In these populations, what is the most significant contributing factor to eating disorders may differ drastically from mainstream assumptions.

Can eating disorders emerge later in life, and are the contributing factors different? Yes, although eating disorders are often associated with adolescence, they can emerge at any age. In midlife or older adults, contributing factors may include grief, menopause, chronic illness, or identity shifts such as divorce or retirement. These life transitions can reignite body dissatisfaction or a desire to regain control, especially if one already possesses internal factors that lead to anorexia. Simultaneously, ageism and health-related stigma can act as external factors that lead to anorexia by reinforcing harmful beliefs about aging and appearance. Exploring what is the most significant contributing factor to eating disorders in older populations opens up crucial avenues for age-inclusive care.

What preventative strategies are most effective in reducing the risk of eating disorders? Prevention requires a comprehensive approach that addresses both individual and systemic contributors. On a personal level, enhancing emotional literacy and resilience can help buffer against internal factors that lead to anorexia. At the societal level, media literacy programs and anti-diet messaging can challenge the external factors that lead to anorexia before they take root. Schools, workplaces, and healthcare systems all have roles to play in reducing risk by promoting healthy relationships with food and body image. By asking what is the most significant contributing factor to eating disorders in specific environments, tailored interventions can be designed to disrupt the cycle before it begins.

Conclusion: Reframing the Narrative Around Eating Disorders for a Healthier Future

Understanding what is the most significant contributing factor to eating disorders requires more than identifying a single root cause—it involves recognizing the profound and complex web of internal and external forces that shape each individual’s experience. Internal factors that lead to anorexia, such as emotional pain, perfectionism, or trauma, intertwine with external factors that lead to anorexia, like media pressure, peer dynamics, and societal ideals, to create a deeply personal but widely misunderstood condition.

By expanding our lens beyond narrow definitions and embracing a more holistic, empathetic perspective, we can begin to dismantle the shame and stigma that surround these disorders. Moreover, a deeper awareness of these contributing factors can inform early intervention, foster resilience, and support more effective treatment strategies. The journey toward healing is never linear, but with understanding, compassion, and multidisciplinary support, recovery is not only possible—it is entirely achievable.

In moving forward, it is essential that we continue to integrate medical research, psychological insight, and cultural awareness in our efforts to prevent and treat eating disorders. Only then can we hope to cultivate a society that values wellness over appearance and fosters environments where all bodies—and the people who live in them—can thrive.

Was this article helpful? Don’t let it stop with you. Share it right now with someone who needs to see it—whether it’s a friend, a colleague, or your whole network. And if staying ahead on this topic matters to you, subscribe to this publication for the most up-to-date information. You’ll get the latest insights delivered straight to you—no searching, no missing out.

Further Reading:

Risk factors for eating disorders: findings from a rapid review