Bulimia nervosa is a complex, often misunderstood eating disorder that affects millions of people around the world. Characterized by recurring cycles of binge eating and purging, it can have devastating effects on physical health, emotional well-being, and social relationships. While it shares some characteristics with other eating disorders, such as anorexia nervosa and binge eating disorder, bulimia nervosa has unique features that require a nuanced understanding. Recognizing the signs and symptoms of bulimia, exploring the psychological and biological causes, and examining effective treatments are all essential steps in increasing awareness and supporting recovery. This article delves into what cycles of binge eating and purging reveal about this disorder, using the principles of medical accuracy and search engine optimization to inform readers and foster meaningful conversations about mental health and nutrition.

You may also like: How to Stop Emotional Eating and Regain Control: Mindful Nutrition Strategies That Support a Healthier Lifestyle

Defining Bulimia Nervosa and Its Core Behaviors

At its core, bulimia nervosa is defined by episodes of uncontrollable binge eating followed by compensatory behaviors such as vomiting, excessive exercise, or the misuse of laxatives to rid the body of consumed calories. These cycles of binging and purging are not isolated incidents but occur frequently, often in secret, and are accompanied by intense feelings of shame, guilt, and distress. The term “bulimic” is commonly used to describe a person with bulimia nervosa, though medical professionals emphasize the importance of person-first language to reduce stigma. Understanding what bulimic means in the context of mental health goes beyond behaviors; it involves comprehending the underlying emotional pain, distorted body image, and anxiety about weight gain that perpetuate the disorder.

When examining the difference between anorexia and bulimia, it’s important to note that while both conditions involve a preoccupation with weight and body shape, they manifest differently. Anorexia nervosa is typically associated with severe restriction of food intake and significant weight loss, whereas bulimia nervosa involves normal or fluctuating body weight due to the nature of binging and purging. Despite these differences, anorexia nervosa vs bulimia nervosa comparisons often reveal shared psychological patterns, including low self-esteem, perfectionism, and a strong desire for control. These overlapping features highlight how disordered eating behaviors can take different forms based on individual experiences and psychological profiles.

Psychological Triggers and Emotional Cycles in Bulimia Nervosa

The recurring cycles of binge eating and purging that define bulimia nervosa are often responses to intense emotional distress. A person with bulimia nervosa may turn to food for comfort during periods of anxiety, loneliness, or self-criticism. The act of bingeing can temporarily numb negative emotions, creating a brief sense of relief. However, this relief is short-lived and quickly replaced by overwhelming guilt and fear of weight gain, which then prompts purging behaviors. This vicious cycle becomes deeply ingrained, creating a pattern that is difficult to break without intervention.

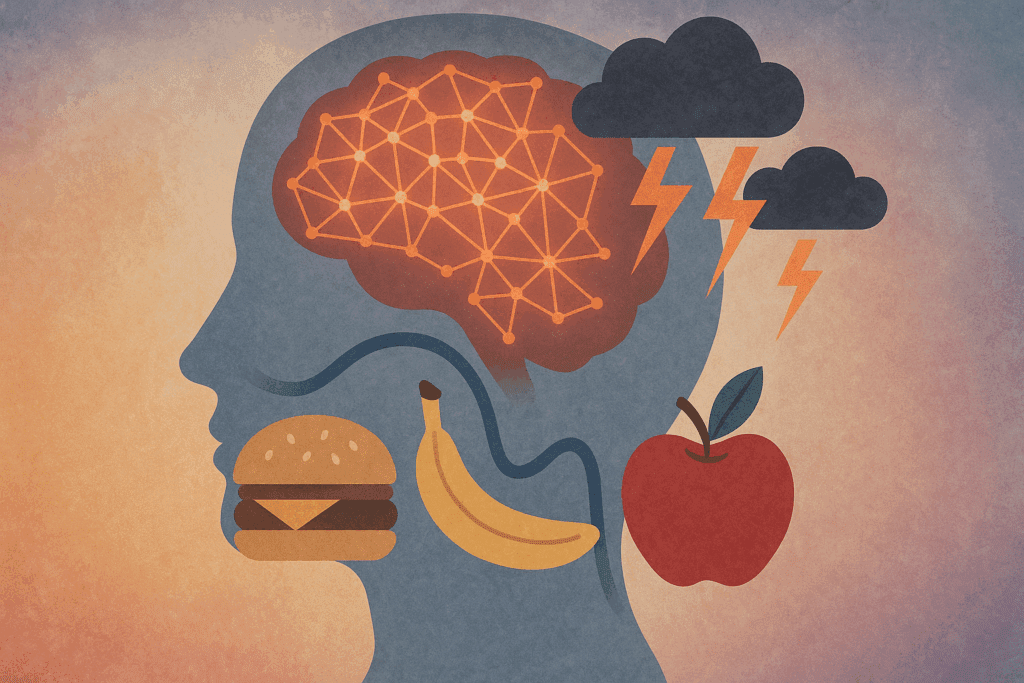

Understanding why people have bulimia nervosa requires a multifactorial perspective. Psychological factors such as childhood trauma, low self-worth, and perfectionism can contribute to the development of disordered eating habits. Additionally, sociocultural pressures—especially those that equate thinness with success, beauty, and moral value—exacerbate body dissatisfaction and drive the compulsion to control weight through harmful means. It is also worth exploring what disorder causes someone to start to worry about weight excessively. In many cases, disordered eating behaviors emerge from underlying conditions like obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety disorders, or major depressive disorder. This intersection of mental health conditions underscores the importance of a comprehensive diagnostic approach.

The Diagnostic Criteria and Warning Signs of Bulimia Nervosa

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), bulimia nervosa is characterized by recurrent episodes of binge eating, followed by inappropriate compensatory behaviors that occur, on average, at least once a week for three months. However, the disorder often goes undetected because individuals may maintain a normal weight, leading others to assume they are healthy. For this reason, understanding when it is considered bulimia is crucial. Diagnostic clarity depends not just on physical signs but on behavioral patterns and psychological distress.

Listening to the symptoms of bulimia—both the visible and the hidden—is essential in identifying those who need support. Some common bulimia nervosa symptoms include frequent visits to the bathroom after meals, swollen cheeks due to salivary gland inflammation, and the presence of calluses on the hands from induced vomiting. Beyond the physical, there are signs of disordered eating that include an obsession with food, calorie counting, or rigid eating rituals. Behavioral red flags, such as secretive eating, social withdrawal, or mood swings, may also suggest that someone is struggling.

To better support early detection, healthcare providers often encourage individuals to listen to symptoms of bulimia as they emerge. Parents, friends, and educators should be aware of the signs and symptoms of bulimia and respond with empathy rather than judgment. The earlier the intervention, the greater the likelihood of successful treatment and recovery.

Understanding the Cycles of Bingeing and Purging

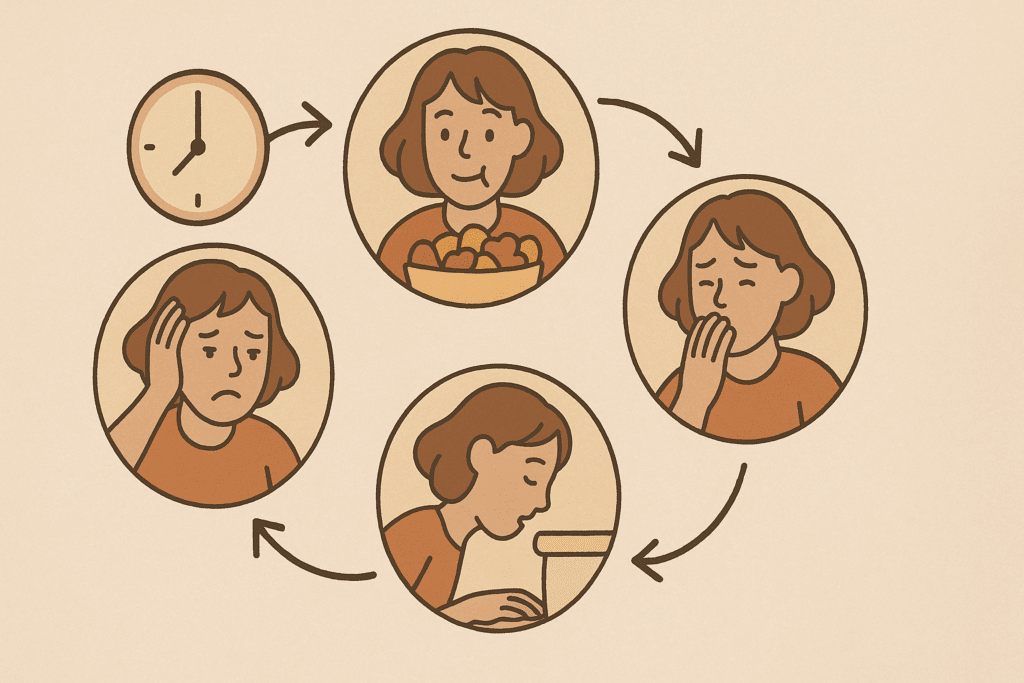

What does bulimic behavior reveal about a person’s internal struggle? The answer lies in the recurring cycles of binge eating and purging, which serve as a coping mechanism for deeper emotional pain. These episodes often follow a predictable sequence: emotional distress triggers a binge, which leads to physical discomfort and guilt, followed by purging as a desperate attempt to regain control. Over time, this pattern becomes neurologically reinforced, creating a feedback loop that is both psychologically and physiologically addictive.

Exploring what cycles of binge eating and purging mean from a clinical perspective offers insight into the complexity of the disorder. Binging is not a matter of simple overeating—it involves the consumption of large quantities of food in a short period, often in a way that feels dissociative or compulsive. Purging, on the other hand, can take many forms, including vomiting, fasting, or excessive exercise. Understanding what purging in food entails helps clarify the physical toll this behavior takes on the digestive system, cardiovascular health, and metabolic balance.

Medical research has shown that the stress of binging and purging can lead to electrolyte imbalances, gastrointestinal damage, and cardiovascular complications. This highlights what are the health risks associated with bulimia—many of which can become life-threatening if left untreated. Additionally, the psychological consequences include depression, anxiety, and an increased risk of substance abuse, further complicating the clinical picture.

Distinguishing Bulimia Nervosa from Other Eating Disorders

In discussions about eating disorders, it is common to ask what is the most common eating disorder. While binge eating disorder is currently the most prevalent, bulimia nervosa remains a significant public health concern, particularly among adolescents and young adults. To better understand these distinctions, it is important to explore bulimia vs binge eating disorder in depth. While both involve episodes of uncontrolled eating, only bulimia includes compensatory behaviors such as purging. This key difference has important implications for diagnosis and treatment.

When comparing bulimia vs binge eating, the emotional aftermath of the behaviors is also telling. Binge eating disorder often involves prolonged feelings of shame but lacks the cyclical pattern of purging that defines bulimia. This is why it’s critical to understand how bulimia and binge eating disorder are similar yet distinct. The motivation behind the behaviors, the coping mechanisms employed, and the health consequences all differ in significant ways.

The anorexia vs bulimia comparison further clarifies the different psychological and behavioral presentations of eating disorders. A person with anorexia may display extreme restriction and fear of weight gain, while a person with bulimia nervosa may fluctuate between indulgence and punishment. Knowing the difference between anorexia and bulimia is crucial for tailoring treatment strategies to the unique needs of each individual. Similarly, understanding the nuances of anorexia nervosa vs bulimia nervosa can inform clinical practice and public education campaigns.

Unpacking the Root Causes of Disordered Eating

Delving into how people get eating disorders requires a nuanced understanding of both nature and nurture. Genetics can play a role, as research has identified hereditary patterns in those with bulimia nervosa. Environmental factors also weigh heavily—exposure to unrealistic body standards, traumatic experiences, and family dynamics can all contribute to the development of disordered eating habits. The interplay of these factors often determines not only the onset but also the severity and progression of the disorder.

Exploring the facts about bulimia helps dismantle myths that often hinder early intervention. For instance, it is a misconception that bulimia only affects young, affluent women. In reality, a person with bulimia nervosa can be of any gender, age, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status. This broad demographic reach underscores the importance of awareness campaigns that do not rely on stereotypes.

Understanding what are the characteristics of bulimia requires an integrative approach. Emotional dysregulation, body image disturbance, impulsivity, and compulsive behaviors all play a role. These traits can overlap with other mental health conditions, which complicates diagnosis but also provides opportunities for holistic treatment. Recognizing the interconnectedness of these characteristics can guide more effective therapeutic interventions.

Treatment and Recovery: Breaking the Cycle

When discussing bulimia nervosa treatments, it is important to emphasize that recovery is possible, though it may require a multifaceted approach. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is considered the gold standard, helping individuals reframe distorted thoughts, develop healthier coping strategies, and gradually reduce binge-purge episodes. Nutritional counseling is also essential, as many individuals with bulimia struggle to establish balanced eating habits and need support in restoring their relationship with food.

In more severe cases, medical intervention may be necessary to address physical complications. For example, those experiencing heart arrhythmias or gastrointestinal issues due to purging may need hospitalization. Medication, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), has also shown promise in reducing bulimic behaviors, particularly when used in conjunction with therapy. Support groups and family-based therapy offer additional layers of care, reinforcing recovery through community and accountability.

Knowing when it is considered bulimia—rather than just occasional overeating or dieting—can make a profound difference in seeking timely help. The earlier the diagnosis, the better the prognosis, particularly when interventions target both the physical symptoms and the underlying emotional causes. For those wondering what does bulimic behavior look like, education is key. Clear, nonjudgmental information empowers individuals and their loved ones to recognize the signs and seek help without shame.

Reflecting on Recovery: A Life Beyond Bulimia

Recovery from bulimia nervosa is not linear, and setbacks are common. However, with consistent support and effective treatment, individuals can learn to replace cycles of binging and purging with healthier coping mechanisms. The journey often involves confronting deep-seated fears, unlearning destructive habits, and cultivating self-compassion. As recovery progresses, individuals report improvements not only in physical health but also in self-esteem, relationships, and quality of life.

It is also essential to continue raising awareness about what does bulimic mean in a broader societal context. Educating the public about the signs of disordered eating, the mental health components of bulimia nervosa, and the availability of evidence-based treatments can reduce stigma and encourage early intervention. Ultimately, the goal is to foster a culture where seeking help is seen as a strength—not a weakness—and where individuals struggling with eating disorders can find hope, healing, and a sense of belonging.

Frequently Asked Questions: Understanding Bulimia Nervosa and Related Eating Disorders

1. How can recurring cycles of binge eating and purging affect long-term brain health? Recurring cycles of binge eating and purging not only damage the digestive system but also have long-term effects on the brain. These behaviors can alter dopamine and serotonin pathways, which are critical for mood regulation and reward processing. Over time, a person with bulimia nervosa may experience cognitive fog, impaired memory, and difficulty with emotional regulation. Chronic stress associated with these cycles also impacts the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which governs the body’s stress response. This disruption may increase vulnerability to depression and anxiety, illustrating how deeply intertwined brain health is with the patterns seen in bulimia nervosa.

2. What makes bulimia nervosa different from high-functioning emotional eating? While emotional eating may involve occasional overeating in response to stress, bulimia nervosa involves a compulsive, recurring pattern of bingeing and purging that disrupts everyday life. The key difference lies in the loss of control and the intensity of compensatory behaviors. Bulimia symptoms often include secretive behavior, fear of gaining weight, and cycles of binging and purging that are both mentally and physically exhausting. High-functioning individuals may hide bulimia nervosa symptoms behind a veneer of normalcy, but their internal experiences are often fraught with shame and distress. Understanding what does bulimic mean in this context highlights the contrast between isolated episodes of overeating and a diagnosable mental health condition.

3. What role does social media play in the rise of bulimia nervosa cases? Social media platforms can amplify unrealistic beauty standards, creating pressure to achieve and maintain a thin ideal. For individuals vulnerable to body image concerns, this can be a trigger for developing disordered eating behaviors. Research suggests that repeated exposure to weight-centric content can lead to obsessive thoughts about food and weight, contributing to what disorder causes someone to start to worry about weight excessively. This can escalate into bulimia nervosa when combined with personality traits like perfectionism or underlying anxiety. For many young users, social validation becomes tied to appearance, intensifying the risk of falling into recurring cycles of binge eating and purging.

4. What are some lesser-known signs of disordered eating that could point to bulimia nervosa? In addition to well-known bulimia nervosa symptoms like purging or overexercising, subtle behavioral patterns may offer early warning signs. These include avoiding meals in social settings, intense fear of losing control while eating, and frequent trips to the restroom during or after meals. Listening to symptoms of bulimia also means noticing shifts in emotional tone, such as increased irritability, withdrawal, or sudden obsession with body-checking habits. Some individuals develop elaborate rituals around eating, such as cutting food into tiny pieces or excessive chewing, as a form of control. These signs of disordered eating can precede more severe manifestations and should not be overlooked.

5. How do healthcare professionals distinguish between anorexia vs bulimia in real-world settings? In clinical practice, distinguishing anorexia vs bulimia involves assessing both physical presentation and behavioral patterns. While anorexia nervosa often presents with significant weight loss and food restriction, bulimia nervosa can occur at any body weight and is characterized by cycles of binging and purging. Healthcare providers look for emotional and psychological markers, such as fear of weight gain, body dissatisfaction, and feelings of being out of control around food. The difference between anorexia and bulimia also lies in the methods of control used—restriction versus purging. These distinctions matter because treatment approaches vary based on whether a patient exhibits more restrictive or compensatory behaviors.

6. What are the implications of misdiagnosing bulimia nervosa as binge eating disorder? Misdiagnosing bulimia nervosa as binge eating disorder can delay proper treatment and increase the risk of physical complications. While both conditions involve episodes of overeating, the absence of purging behaviors in binge eating disorder differentiates it from bulimia. Understanding how bulimia and binge eating disorder are similar yet distinct is essential for effective intervention. Inaccurate diagnosis can result in treatment plans that fail to address the purging component, leaving cycles of binging and purging unchallenged. Furthermore, emotional support strategies for bulimia differ, as a person with bulimia nervosa often experiences more intense guilt and self-punishment than those with binge eating disorder.

7. What long-term physical health risks are unique to bulimia nervosa? Although all eating disorders carry health risks, bulimia nervosa poses some unique dangers due to the purging behaviors involved. Frequent vomiting can erode tooth enamel, cause electrolyte imbalances, and lead to irregular heart rhythms that may become life-threatening. Additionally, recurrent laxative use can result in chronic gastrointestinal issues and dependency. One of the often-overlooked facts about bulimia is that it can also impair fertility and disrupt hormone function in both women and men. These examples illustrate what are health risks associated with bulimia that make early detection and treatment vital.

8. How can families support a person with bulimia nervosa without reinforcing harmful behaviors? Supporting a person with bulimia nervosa requires a delicate balance between empathy and accountability. Families should avoid commenting on weight or eating habits and instead focus on emotional support and open communication. Encouraging professional help without judgment helps reduce the shame that often accompanies binging and purging. Education about what purging in food really means can help families understand that these behaviors are not about vanity but are coping mechanisms for deep emotional pain. Creating a safe, non-critical environment can make a significant difference in recovery outcomes.

9. Are there any new or alternative bulimia nervosa treatments being explored? In addition to traditional cognitive-behavioral therapy and medication, researchers are exploring new approaches to bulimia nervosa treatments, including neurofeedback, virtual reality therapy, and gut-brain axis interventions. These emerging methods aim to regulate neural circuits associated with impulse control, anxiety, and reward. Another promising development is the integration of mindfulness-based interventions with nutritional counseling to disrupt the recurring cycles of binge eating and purging. Advances in personalized medicine, such as genetic testing, may one day help identify which bulimia nervosa treatments work best for specific individuals. These innovations represent a shift toward more holistic and individualized care models.

10. What steps can schools and universities take to prevent bulimia and other eating disorders? Educational institutions play a critical role in identifying and preventing eating disorders. They can implement peer-led workshops on body image, offer access to mental health counseling, and ensure nutrition education is framed around balance rather than restriction. Raising awareness about what is the most common eating disorder and the difference between anorexia and bulimia can equip students with knowledge to support peers in distress. Schools should also train staff to recognize signs and symptoms of bulimia, such as frequent absences after lunch or unusual eating patterns. Prevention starts with a culture of inclusivity, where appearance is not tied to worth and students feel safe seeking help.

The Importance of Awareness: What Bulimia Teaches Us About Mental Health and Nutrition

Understanding bulimia nervosa and the recurring cycles of binge eating and purging provides more than just clinical insight—it reveals the deep connection between emotional well-being, body image, and nutritional health. These cycles are not simply about food; they are expressions of inner turmoil, perfectionism, and the struggle for control. By examining what are the characteristics of bulimia, what purging in food means, and how bulimia and binge eating disorder are similar, we gain a more complete picture of the challenges individuals face.

Awareness also means challenging assumptions about who is affected and why. A person with bulimia nervosa may be high-achieving, outwardly confident, and seemingly well-adjusted, masking their internal distress. Recognizing the signs and symptoms of bulimia—both subtle and overt—requires sensitivity, education, and a willingness to engage in difficult conversations.

As we strive for a healthier lifestyle and more mindful relationship with food, we must prioritize mental health as an integral component of overall wellness. From understanding bulimia vs binge eating to exploring bulimia nervosa treatments, the journey begins with empathy, knowledge, and action. By supporting those affected and advocating for comprehensive care, we can transform our approach to eating disorders—and in doing so, promote a culture of healing, self-respect, and lasting change.

Was this article helpful? Don’t let it stop with you. Share it right now with someone who needs to see it—whether it’s a friend, a colleague, or your whole network. And if staying ahead on this topic matters to you, subscribe to this publication for the most up-to-date information. You’ll get the latest insights delivered straight to you—no searching, no missing out.