The complex relationship between obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and eating disorders is a subject of growing clinical interest and public awareness. While both conditions have distinct diagnostic criteria, their overlap is not only possible but surprisingly common. When obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviors start to interfere with an individual’s relationship with food, the resulting pattern can have profound consequences for both mental and physical health. From a clinical and lifestyle perspective, recognizing the early signs of food-related compulsions and understanding their roots in obsessive-compulsive thinking is essential for anyone navigating these challenges. This article delves into the psychological dynamics of OCD and eating disorders, exploring how the intersection of these two disorders can disrupt nutritional balance and overall mental wellness.

You may also like: How to Stop Emotional Eating and Regain Control: Mindful Nutrition Strategies That Support a Healthier Lifestyle

Defining the Relationship Between OCD and Eating Disorders

OCD is a psychiatric condition characterized by intrusive, unwanted thoughts (obsessions) and repetitive behaviors or mental acts (compulsions) performed in an attempt to reduce anxiety. Eating disorders, such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder, are mental health conditions marked by disturbances in eating behaviors and related thoughts and emotions. Although distinct, OCD and eating disorders often share underlying psychological traits, including perfectionism, anxiety sensitivity, and a heightened need for control. When these conditions co-occur, they can reinforce one another in ways that deepen psychological distress and complicate treatment.

Research has shown that individuals diagnosed with anorexia and OCD often experience a significantly higher level of symptom severity and functional impairment than those with only one of the disorders. The overlapping mechanisms of rigid thinking, compulsive rituals, and distorted beliefs about control, purity, or self-worth create a synergistic effect. In many cases, obsessive thoughts about body image, food purity, or calorie intake become fused with compulsive behaviors such as food restriction, ritualized eating patterns, or excessive exercise. This intersection is not merely theoretical; it reflects real-world clinical cases where obsessive-compulsive disorder eating disorders evolve into debilitating, intertwined conditions.

Understanding Food OCD: When Eating Becomes a Compulsion

Food OCD refers to a subtype of OCD in which intrusive thoughts and compulsive rituals are centered around food, eating, or contamination fears. This manifestation of OCD may not be listed in standard diagnostic manuals as a standalone diagnosis, but it is increasingly recognized by clinicians as a significant contributor to disordered eating. Common expressions of food OCD include extreme fears of contamination from certain foods, obsessive checking of food expiration dates, avoidance of food prepared by others, or highly rigid food preparation rituals.

These behaviors may be mistaken for dietary preferences or quirky habits, but the key distinguishing factor is the level of distress and functional impairment they cause. A person with food OCD is not simply careful; they are consumed by anxiety and feel compelled to perform rituals to alleviate it. This can lead to social isolation, malnutrition, and an overall deterioration in mental health. In many cases, the obsessive thoughts are deeply rooted in fears about health, purity, or moral judgments about food, which aligns with patterns observed in eating disorders. As such, food OCD often coexists with or transitions into anorexia or other restrictive eating patterns, making early identification critical.

Anorexia and OCD: Exploring the Symbiotic Connection

Among the various eating disorders, anorexia nervosa has the most well-documented association with OCD. Individuals with anorexia often display obsessive thoughts about weight, body image, and food intake, alongside compulsive behaviors such as calorie counting, excessive exercise, or ritualistic eating. These behaviors mirror the classic OCD cycle of obsession and compulsion, reinforcing the notion that anorexia and OCD can be mutually reinforcing disorders.

One hypothesis for the strong connection between anorexia and OCD is that both conditions serve as maladaptive coping mechanisms for managing anxiety. The rigidity and predictability of food rituals in anorexia provide a false sense of control in an otherwise unpredictable world. This mirrors the function of compulsions in OCD, which are performed to neutralize distressing thoughts. When these mechanisms overlap, the result is often a highly structured but emotionally exhausting lifestyle that prioritizes order over nourishment. In extreme cases, this leads to severe malnutrition, organ damage, and a heightened risk of mortality.

Treatment for individuals with both anorexia and OCD requires a careful, integrated approach that addresses both the disordered eating and the underlying compulsive behaviors. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), particularly exposure and response prevention (ERP), has shown promise in treating both conditions. However, treatment must be tailored to the individual, as the presence of one disorder can interfere with progress in addressing the other. For example, exposure exercises aimed at challenging food fears in anorexia may trigger obsessive thoughts, requiring a delicate balance between confronting fears and maintaining nutritional stability.

How Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Eating Disorders Affect Nutritional Health

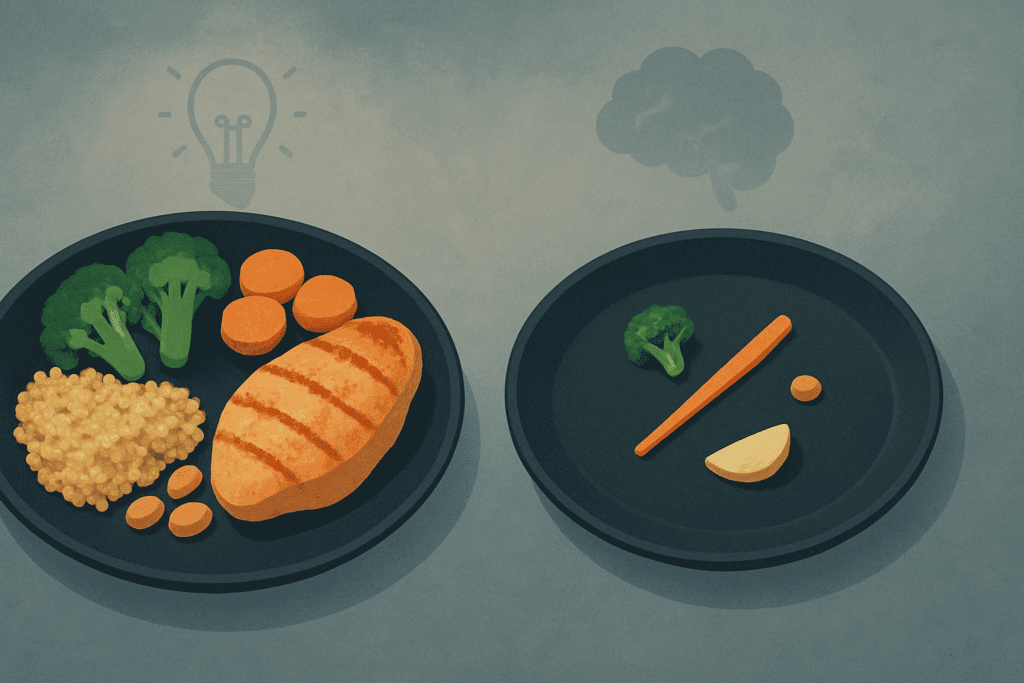

One of the most concerning consequences of the overlap between OCD and eating disorders is the impact on nutritional health. When individuals engage in obsessive food rituals or restrictive eating, their intake of essential nutrients can become severely compromised. This is particularly true in cases of food OCD where fears of contamination or impurity lead to the avoidance of entire food groups or categories of ingredients. Over time, this behavior can result in deficiencies in key vitamins and minerals, impairing everything from immune function to cognitive performance.

The consequences of nutritional deficiencies are not only physical but also psychological. A lack of omega-3 fatty acids, for instance, has been linked to mood disorders, while deficiencies in B vitamins can impair memory and concentration. When the brain is not adequately nourished, obsessive-compulsive symptoms may worsen, creating a vicious cycle. In this context, treating OCD and eating disorders is not just a matter of changing thoughts and behaviors but also of restoring the body’s biochemical balance through proper nutrition.

It is also important to recognize that some individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder eating disorders may misuse nutritional labels, dietary trends, or health advice to justify their compulsions. For instance, someone with food OCD might insist on eating only “clean” or organic foods, not out of preference but due to an irrational fear of contamination. While society often praises discipline in food choices, this admiration can mask serious psychological distress and prevent individuals from seeking help. As such, awareness campaigns and public education efforts should aim to differentiate between health-conscious behavior and pathological compulsion.

Psychological Mechanisms Behind Food OCD and Disordered Eating

Understanding the psychological mechanisms that drive food OCD and its connection to eating disorders requires a closer look at cognitive distortions and anxiety regulation. Many individuals with these conditions engage in black-and-white thinking, where foods are labeled as entirely good or bad, safe or unsafe. This binary thinking is a hallmark of both OCD and restrictive eating disorders, contributing to rigid behaviors and emotional distress when dietary rules are broken.

In addition, compulsive behaviors related to food often serve a function beyond avoiding harm; they provide temporary relief from anxiety or distress. This reinforcement cycle makes the behaviors more resistant to change, as the individual begins to associate rituals with emotional regulation. Over time, these behaviors become deeply ingrained, making them harder to extinguish even when they lead to negative health outcomes.

The role of trauma and early life experiences should also be considered. Some individuals report a history of critical comments about weight, exposure to rigid household rules about food, or traumatic experiences related to illness or contamination. These experiences can shape an individual’s beliefs about food and health, laying the groundwork for obsessive-compulsive behaviors. Addressing these underlying psychological drivers is essential for lasting recovery and requires the expertise of mental health professionals trained in trauma-informed care.

Challenges in Diagnosis and Misunderstood Symptoms

One of the major hurdles in addressing OCD and eating disorders is the difficulty in accurate diagnosis. Many people with food OCD or obsessive-compulsive disorder eating disorders do not seek help until their symptoms have become severe. Additionally, their behaviors may be misinterpreted by loved ones or even healthcare professionals as dieting, food allergies, or lifestyle choices rather than signs of psychological distress.

This problem is compounded by the normalization of restrictive eating in many cultures. Phrases like “clean eating,” “detoxing,” or “intermittent fasting” are often promoted as wellness strategies, even when they may disguise compulsive or obsessive behaviors. This cultural backdrop makes it harder to identify when a behavior has crossed the line from healthy to harmful. A person might insist on avoiding gluten, for example, without any medical reason, purely due to an obsessive belief that it is inherently dangerous. In such cases, the behavior may appear health-driven, but its underlying motivation is rooted in anxiety and compulsion.

To ensure accurate diagnosis and effective treatment, clinicians must take a holistic view of each patient’s eating patterns, emotional triggers, and cognitive processes. This includes asking detailed questions about the individual’s motivations, distress levels, and the consequences of their behaviors on daily life. A multi-disciplinary team approach, involving dietitians, therapists, and medical doctors, is often the most effective strategy for comprehensive assessment and care.

Strategies for Treatment and Recovery

Addressing the intersection of OCD and eating disorders requires an integrated, individualized treatment approach. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), particularly exposure and response prevention (ERP), remains the gold standard for treating OCD and has also proven effective in eating disorder recovery. In ERP, individuals are gradually exposed to anxiety-provoking stimuli (such as eating feared foods) and supported in resisting the urge to engage in compulsive behaviors. Over time, this reduces the power of obsessive thoughts and helps rewire the brain’s anxiety response.

However, ERP alone may not address the complex nutritional and emotional needs of someone with co-occurring disorders. Nutritional rehabilitation, under the guidance of a registered dietitian experienced in eating disorders, is essential to restore physical health and normalize eating patterns. Nutritional counseling can also help individuals challenge food-related fears, dismantle harmful beliefs about food, and develop a balanced approach to eating.

Psychopharmacology can play a supportive role, particularly when symptoms are severe or resistant to therapy alone. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), commonly used for OCD, have shown some efficacy in reducing obsessive-compulsive symptoms in individuals with eating disorders. However, medication must be carefully managed, especially when weight and nutritional status are unstable.

Equally important is the cultivation of self-compassion and mindfulness. Many individuals with OCD and eating disorders struggle with intense self-criticism, shame, and guilt. Mindfulness-based therapies, such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), can help individuals detach from obsessive thoughts and reconnect with their values. Recovery is not a linear process, and setbacks are common, but with the right support, individuals can build resilience and re-establish a healthy relationship with food and their bodies.

Promoting Awareness and Reducing Stigma

To foster meaningful change in how society approaches OCD and eating disorders, we must move beyond stereotypes and misinformation. Public health campaigns should emphasize the complexity of these conditions and the importance of early intervention. Schools, universities, and workplaces can play a crucial role by offering educational programs that teach emotional resilience, media literacy, and healthy coping strategies.

In clinical settings, ongoing professional development is essential to help providers recognize the nuanced ways in which OCD and eating disorders can manifest. For example, a patient who presents with gastrointestinal complaints might actually be struggling with food OCD, leading to self-imposed dietary restrictions that mimic symptoms of medical conditions. Only through careful assessment and a nonjudgmental approach can clinicians uncover the true nature of such behaviors.

Friends and family members also have a vital role to play in supporting recovery. Understanding the difference between preferences and compulsions can help loved ones provide appropriate encouragement and avoid unintentionally reinforcing harmful behaviors. Creating a supportive environment where individuals feel safe discussing their struggles without fear of judgment can make a significant difference in their willingness to seek help.

Frequently Asked Questions: OCD and Eating Disorders

What are some early warning signs that food-related behaviors might be linked to OCD rather than personal preference? While everyone has food preferences, early signs that suggest a link to food OCD include intense distress when those preferences are disrupted and the compulsive need to prepare or consume food in a rigid, ritualistic way. Individuals might avoid social meals due to fear of contamination, become preoccupied with food labels to an excessive degree, or insist on eating at the same time each day regardless of hunger. These behaviors go beyond healthy eating and reflect an obsessive desire to reduce anxiety. In many cases, what begins as a seemingly innocuous routine can escalate into more disabling patterns. Understanding the relationship between food OCD and obsessive compulsive disorder eating disorders can help differentiate between a structured diet and a disorder rooted in anxiety.

Can OCD be a risk factor for developing an eating disorder later in life? Yes, OCD can increase the risk of developing an eating disorder, particularly when food or body image becomes a focus of obsessive thoughts. For example, an individual with contamination-based OCD might avoid entire food groups, eventually leading to nutritional deficiencies or restrictive patterns. Similarly, someone who obsesses over control and perfection might channel these compulsions into dieting or exercise, potentially triggering anorexia and OCD behaviors simultaneously. The overlap between OCD and eating disorders is particularly pronounced during stressful life transitions, such as adolescence or major changes in routine. Recognizing these risk factors early can prevent the progression to full-blown obsessive compulsive disorder eating disorders.

Is it possible to treat food OCD without addressing the eating disorder, or must they be treated together? Treating food OCD in isolation may offer temporary relief but often leaves deeper disordered eating behaviors unresolved. Since food OCD and eating disorders frequently reinforce each other, effective treatment generally requires an integrated approach. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), especially exposure and response prevention (ERP), can be adapted to address both the obsessive thought patterns and the disordered eating rituals. Nutrition therapy should also accompany psychological treatment to rebuild a healthy relationship with food. When OCD and eating disorders coexist, comprehensive care is essential to prevent symptom substitution and long-term relapse.

How can parents or loved ones distinguish between healthy eating and food OCD in adolescents? Adolescents may experiment with new diets or food trends, but warning signs of food OCD include extreme rigidity, distress over deviations, and a lack of flexibility in food choices. When food becomes a source of anxiety rather than enjoyment, or when rituals begin to interfere with school, sleep, or social life, it may signal a deeper issue. In particular, parents should watch for compulsive label-checking, fear-based food avoidance, and secrecy around eating habits. These behaviors may reflect a developing pattern of OCD and eating disorders rather than a simple interest in health. Early intervention, open communication, and professional evaluation can make a crucial difference in these cases.

What role does perfectionism play in the development of anorexia and OCD? Perfectionism is a common psychological trait shared by individuals with both anorexia and OCD, often manifesting as an unrelenting pursuit of control, flawlessness, or moral purity. In the context of anorexia and OCD, perfectionism can drive extreme behaviors such as excessive exercise, obsessive calorie tracking, or rigid adherence to dietary rules. This desire for perfection often masks deeper feelings of inadequacy or anxiety, and it can create a cycle where any deviation from self-imposed rules results in guilt or panic. While perfectionism is not inherently pathological, its intensity and function in obsessive compulsive disorder eating disorders can be highly damaging. Addressing perfectionist thinking is a core component of many therapeutic interventions.

Are there cultural or societal influences that may exacerbate food OCD and eating disorders? Yes, societal messages around clean eating, body image, and productivity can reinforce the development of OCD and eating disorders. For instance, social media often glamorizes dietary restriction, labeling certain foods as “bad” or “toxic,” which can resonate dangerously with individuals prone to obsessive thinking. Cultural emphasis on thinness or discipline can further normalize behaviors rooted in anxiety, making it harder to distinguish between dedication and disordered eating. The increasing prevalence of wellness culture has also contributed to a rise in food OCD, as health-based obsessions become socially validated. It’s important to critically evaluate these influences and promote mental health literacy around food and body norms.

What are some emerging treatment approaches for obsessive compulsive disorder eating disorders? Beyond traditional CBT and ERP, emerging approaches include Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), which focuses on values-based action and mindfulness rather than symptom control. ACT can be particularly effective for those who struggle with shame, rigidity, or identity enmeshment tied to OCD and eating disorders. Another promising intervention is Compassion-Focused Therapy (CFT), which helps individuals develop self-kindness in the face of intrusive thoughts and compulsive behaviors. Technological advances, such as virtual reality exposure and mobile-based interventions, are also expanding access to care. These therapies recognize the nuanced ways in which anorexia and OCD intersect, offering a more holistic path to recovery.

Can obsessive thoughts about food develop in individuals who have never been diagnosed with OCD? Yes, obsessive food thoughts can emerge even in people without a formal OCD diagnosis, especially during periods of stress, trauma, or major lifestyle changes. While these individuals may not meet diagnostic criteria for OCD, they can still develop problematic patterns that resemble food OCD or other eating-related obsessions. The line between disordered eating and full-fledged obsessive compulsive disorder eating disorders is often a matter of intensity, duration, and functional impairment. Early signs, such as growing fear around eating unfamiliar foods or an escalating need for dietary control, should be monitored carefully. Seeking help early—even before a diagnosis—is a proactive way to prevent escalation.

What strategies can support long-term recovery from food OCD and eating disorders? Sustaining recovery from food OCD and eating disorders requires more than symptom reduction; it involves reshaping one’s identity, rebuilding trust in the body, and cultivating emotional resilience. Long-term strategies include regular therapeutic support, relapse prevention planning, and participation in recovery communities. Engaging in intuitive eating practices, body neutrality, and mindfulness-based stress reduction can foster a healthier relationship with food and self. It’s also important to monitor major life transitions, as stress and change can trigger old patterns. Recovery is not a destination but a dynamic process that evolves as individuals continue to grow and redefine their lives outside the constraints of OCD and eating disorders.

How can professionals in healthcare and nutrition better recognize the signs of food OCD in their patients? Healthcare and nutrition professionals can better detect food OCD by going beyond surface-level dietary assessments and exploring the emotional and behavioral motivations behind food choices. Asking open-ended questions about food preparation, mealtime stress, and coping strategies can uncover obsessive patterns that may otherwise be overlooked. Collaboration between dietitians, therapists, and physicians is crucial for diagnosing and treating anorexia and OCD when they co-occur. Continuous education on the nuances of obsessive compulsive disorder eating disorders can also enhance early identification. By creating a safe, stigma-free environment, professionals can encourage honest conversations that lead to more accurate diagnoses and effective care.

A Holistic Path Forward: Integrating Mental and Nutritional Wellness

The connection between OCD and eating disorders is both clinically significant and deeply personal for those affected. When obsessive thoughts begin to shape eating behaviors, they can spiral into dangerous patterns that compromise not just physical health, but emotional well-being as well. Recognizing the signs of food OCD, understanding the interplay between anorexia and OCD, and appreciating the broader category of obsessive-compulsive disorder eating disorders are essential steps toward effective prevention and intervention.

The path to recovery involves more than symptom management; it requires a commitment to restoring balance, nourishing the body, and healing the mind. Through integrated care that combines cognitive-behavioral therapy, nutritional support, and emotional healing, individuals can learn to challenge compulsions, embrace flexibility, and rebuild a healthy relationship with food. Promoting awareness, reducing stigma, and fostering compassionate care are essential not only for those currently struggling, but also for creating a culture that values mental health and holistic wellness. In doing so, we affirm that nourishment goes beyond calories—it involves how we think, feel, and live.

Was this article helpful? Don’t let it stop with you. Share it right now with someone who needs to see it—whether it’s a friend, a colleague, or your whole network. And if staying ahead on this topic matters to you, subscribe to this publication for the most up-to-date information. You’ll get the latest insights delivered straight to you—no searching, no missing out.