Anxiety is often viewed through the lens of psychological stress, past trauma, or neurochemical imbalances. However, a growing body of scientific literature and clinical observation points to an unexpected but increasingly recognized trigger: food. For some individuals, what they eat may significantly impact how they feel mentally and emotionally. This phenomenon, known as food-induced anxiety, invites an important question—can food truly trigger anxiety, and if so, what can be done to manage the resulting symptoms, including the distressing experience of a panic attack after eating?

You may also like: How to Stop Emotional Eating and Regain Control: Mindful Nutrition Strategies That Support a Healthier Lifestyle

Understanding the Complex Relationship Between Food and Anxiety

The interplay between diet and mental health is complex and multifaceted. While it is well-known that poor nutrition can impair cognitive function and emotional stability, the specific link between food and anxiety is only recently gaining widespread clinical attention. Food-induced anxiety refers to anxiety symptoms that either arise or intensify following the consumption of certain foods. These reactions may be tied to physiological responses, such as blood sugar fluctuations, food sensitivities, or gastrointestinal distress, all of which can activate the body’s stress response.

The human brain and gut are closely connected through the gut-brain axis, a bidirectional communication system involving neural, hormonal, and immunological signaling. When the digestive system is upset—whether due to poor food choices, underlying gut conditions, or intolerances—it can send stress signals to the brain. This may result in a feeling of unease, restlessness, or full-blown anxiety. For people prone to anxiety disorders, even mild gastrointestinal discomfort can heighten mental distress.

It’s also important to consider the role of nutrient deficiencies. Inadequate intake of essential nutrients like magnesium, omega-3 fatty acids, B vitamins, and amino acids has been associated with increased anxiety symptoms. When the brain lacks the raw materials it needs to produce neurotransmitters such as serotonin and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), mood regulation becomes impaired. As such, food-induced anxiety can arise not just from what is eaten but from what is lacking in the diet.

Recognizing the Signs of Anxiety After Eating

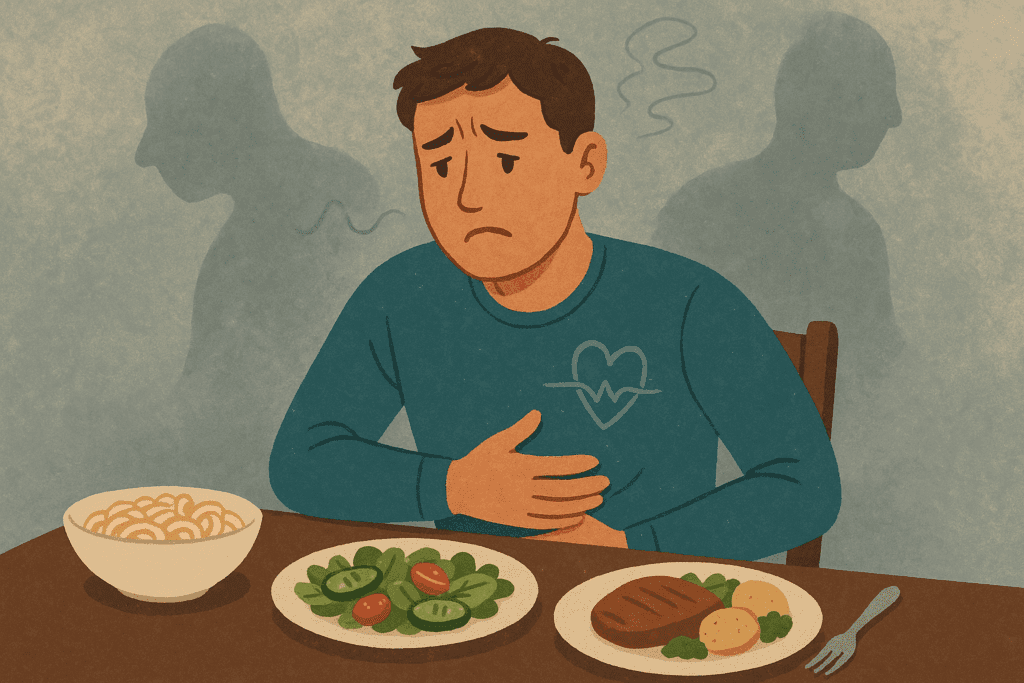

For many individuals, anxiety after eating can feel mystifying and deeply unsettling. One moment, they may be enjoying a meal, and shortly thereafter, experience a cascade of mental and physical symptoms—racing heart, shortness of breath, dizziness, nausea, or an overwhelming sense of dread. These symptoms often overlap with those of panic attacks, which can be terrifying when they occur without warning or an obvious cause.

The key to recognizing anxiety after eating lies in identifying patterns. Does anxiety consistently arise after consuming certain types of food, such as sugar, caffeine, or processed carbohydrates? Do symptoms tend to appear within a specific time frame following a meal? Is there a history of food sensitivities, irritable bowel syndrome, or other digestive issues that could be contributing to the problem?

It’s crucial to differentiate between anxiety that is truly food-induced and anxiety that is triggered by other factors, such as social dining situations or restrictive eating patterns. Sometimes, the act of eating itself becomes a stressor for individuals with food anxiety—a condition in which fear, guilt, or worry about eating certain foods becomes a recurring theme. This emotional distress can further exacerbate physiological symptoms and reinforce the anxiety cycle.

How Food Sensitivities and Intolerances Contribute to Food-Induced Anxiety

Food sensitivities, intolerances, and allergies represent a significant but often overlooked factor in the development of food-induced anxiety. Unlike food allergies, which trigger an immediate immune response, food sensitivities may lead to delayed reactions that manifest as mood changes, fatigue, and gastrointestinal symptoms—many of which are also common in anxiety disorders.

One well-documented example is gluten sensitivity. Although gluten intolerance is most commonly associated with celiac disease, non-celiac gluten sensitivity can also produce a range of neurological and psychological symptoms, including brain fog, irritability, and anxiety. Similarly, lactose intolerance can lead to bloating and cramping, which may cause discomfort and, in anxious individuals, fuel a fear response.

Additionally, artificial additives, preservatives, and colorings found in processed foods have been implicated in mood disturbances. Some studies suggest that these substances may interfere with neurotransmitter function or promote inflammation, both of which can negatively affect mental health. For people with heightened sensitivity to these chemicals, even small amounts can result in pronounced anxiety symptoms.

Blood Sugar Spikes and Crashes: A Common Culprit

One of the most common physiological mechanisms behind food-induced anxiety is blood sugar instability. When we consume high-glycemic foods—those that rapidly elevate blood glucose levels—the body releases a surge of insulin to bring blood sugar back down. This response can lead to a subsequent crash, causing symptoms like shakiness, irritability, fatigue, and a sense of nervousness that closely mimics anxiety.

Frequent blood sugar fluctuations can disrupt the body’s natural homeostasis, leaving individuals in a state of metabolic stress. Over time, this can contribute to adrenal fatigue, insulin resistance, and heightened cortisol levels—all of which may compound the experience of anxiety. Individuals who experience panic attacks after eating may be particularly sensitive to these shifts in blood sugar.

To mitigate these effects, it is recommended to consume meals that include complex carbohydrates, fiber, protein, and healthy fats, which help slow the absorption of glucose and promote stable energy levels. Regular, balanced meals can act as a buffer against mood swings and help regulate the body’s stress response. Being mindful of how different foods affect blood sugar levels is a practical step toward reducing anxiety after eating.

Gut Health, Inflammation, and the Brain

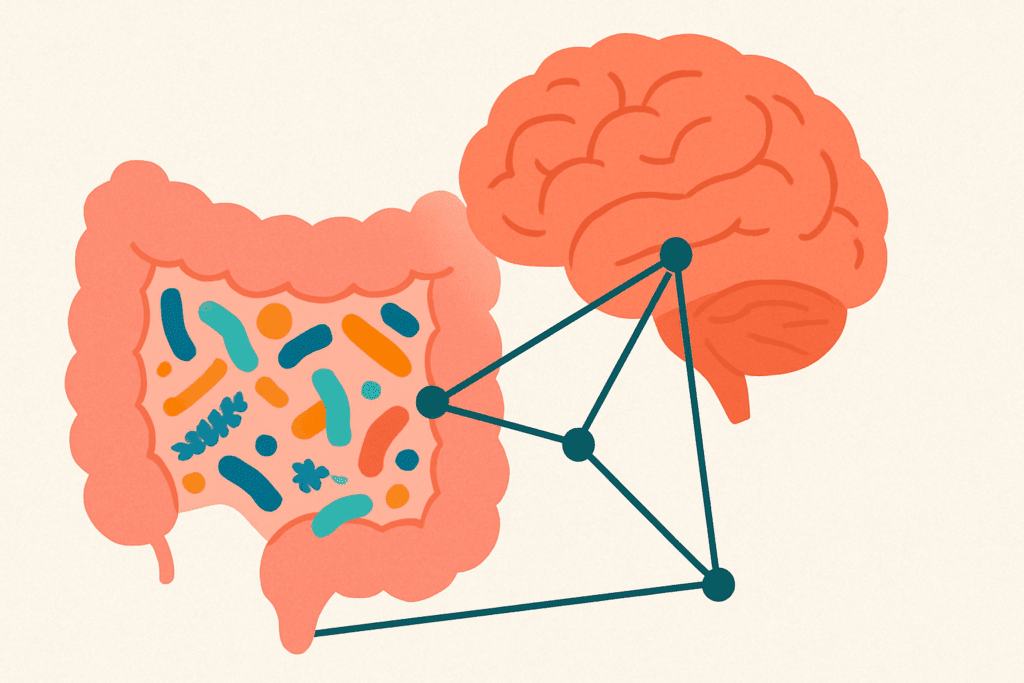

An increasing number of studies underscore the importance of gut health in regulating mental well-being. The gut microbiome—a diverse ecosystem of microorganisms living in the digestive tract—plays a critical role in neurotransmitter production, immune function, and inflammation. Disruptions in the gut microbiome have been linked to a wide array of mental health conditions, including anxiety, depression, and panic disorders.

Food choices directly influence the composition of the microbiome. Diets high in refined sugars, artificial sweeteners, and saturated fats have been shown to reduce microbial diversity and promote the growth of pro-inflammatory bacteria. Conversely, diets rich in whole foods, particularly those containing prebiotic fibers and fermented foods, support a healthy gut environment that may protect against food-induced anxiety.

When gut inflammation becomes chronic, it can increase intestinal permeability, a condition often referred to as “leaky gut.” This allows endotoxins and partially digested food particles to enter the bloodstream, triggering systemic inflammation that may reach the brain. Neuroinflammation is a recognized contributor to anxiety and other mood disorders, suggesting that improving gut health may alleviate symptoms of food anxiety and reduce the likelihood of a panic attack after eating.

The Psychological Dimension of Food Anxiety

While much attention is paid to the biological pathways through which food may trigger anxiety, the psychological dimension is equally important. For individuals with food anxiety, meals can become a source of dread rather than nourishment. This fear may stem from past experiences of discomfort after eating, rigid dietary rules, or a distorted relationship with body image and control.

Disordered eating patterns, such as orthorexia or restrictive dieting, can intensify food-related anxiety. The internal narrative becomes one of fear—fear of eating the wrong food, fear of gaining weight, or fear of triggering a physical reaction. Over time, this anxiety becomes self-perpetuating, reinforcing hypervigilance around food and making it difficult to enjoy meals.

Social situations can further complicate matters. Dining out, attending parties, or eating in public may provoke significant anxiety for those worried about digestive upset or panic attacks. The anticipation of judgment, embarrassment, or lack of control can make eating an emotionally fraught experience. In these cases, therapy and nutritional counseling may be essential tools for breaking the cycle and promoting healthier, more confident relationships with food.

Practical Strategies for Managing Food-Induced Anxiety

Managing food-induced anxiety requires a multifaceted approach that addresses both physiological and psychological factors. First and foremost, keeping a detailed food and symptom journal can help identify potential triggers. Recording meals, ingredients, timing, and emotional responses allows individuals to notice patterns and correlations that may otherwise go undetected.

Working with a qualified nutritionist or integrative physician can provide clarity on whether underlying food sensitivities or nutritional imbalances are contributing to anxiety after eating. Comprehensive testing, such as food sensitivity panels, micronutrient assessments, and gut health evaluations, can guide targeted dietary adjustments. These changes should be gradual, evidence-based, and sustainable—extreme elimination diets can sometimes increase food anxiety rather than resolve it.

Mindful eating practices can also make a significant difference. Slowing down at meals, chewing thoroughly, and focusing on the sensory experience of eating can reduce stress and improve digestion. Avoiding distractions like screens while eating promotes interoceptive awareness—the ability to tune in to bodily sensations—which is essential for recognizing hunger, fullness, and emotional responses to food.

In cases where anxiety is pronounced or interferes with daily life, mental health support may be necessary. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), exposure therapy, and somatic-based approaches can help individuals reframe negative thoughts around food and regain a sense of safety and control. These interventions are particularly helpful for those experiencing panic attacks after eating or struggling with food anxiety rooted in trauma or past experiences.

Building a Nourishing, Anxiety-Reducing Diet

While food can be a trigger for anxiety, it can also be a powerful tool for healing. A nourishing diet rich in whole, unprocessed foods supports mental health by stabilizing blood sugar, reducing inflammation, and supplying the nutrients needed for optimal brain function. Emphasizing foods that promote gut health—such as leafy greens, legumes, yogurt, kefir, and fermented vegetables—can enhance microbial diversity and improve mood regulation.

Incorporating omega-3 fatty acids from sources like fatty fish, walnuts, and flaxseeds may help reduce anxiety symptoms by supporting anti-inflammatory pathways and promoting neuroplasticity. Magnesium-rich foods such as spinach, almonds, and black beans have been shown to have calming effects, while B-vitamin complexes, found in whole grains, eggs, and nutritional yeast, play a vital role in neurotransmitter synthesis.

Herbal remedies and adaptogens, such as ashwagandha, chamomile, and lemon balm, may offer additional support, especially when used under the guidance of a healthcare provider. These natural options can gently reduce stress responses without the side effects associated with conventional medications. However, dietary supplements should never replace professional mental health treatment or a balanced eating plan.

Importantly, a supportive and non-restrictive approach to nutrition is essential. Instead of focusing on fear-based food avoidance, individuals should be encouraged to explore how different foods make them feel and to cultivate curiosity rather than judgment around eating. This mindset shift can help reduce food anxiety and restore a sense of empowerment at the table.

Frequently Asked Questions: Food-Induced Anxiety and Panic After Eating

1. Can long-term dietary patterns influence the development of food-induced anxiety? Absolutely. Over time, consistently consuming a diet high in ultra-processed foods, refined sugars, and artificial additives can create an internal environment that is more prone to anxiety responses. When the gut microbiome is continually exposed to inflammatory foods, it may shift toward dysbiosis, a condition that has been increasingly linked to mood instability and heightened sensitivity to stress. This can set the stage for chronic food-induced anxiety, where even moderate dietary deviations trigger discomfort. Additionally, long-term nutritional imbalances—such as low levels of magnesium, omega-3s, or tryptophan—can subtly impair neurotransmitter function, leading to a gradual erosion of emotional resilience. Over time, these patterns may not only exacerbate anxiety after eating but also make panic responses more likely.

2. Is food anxiety more common in individuals with a history of eating disorders? Yes, individuals with past or present eating disorders often experience heightened food anxiety due to their history of restrictive or controlling food behaviors. The psychological residue from disordered eating can make reintroducing feared foods deeply triggering, even in small amounts. For these individuals, food-induced anxiety is not just about physical reactions, but also about psychological trauma associated with body image, control, and fear of weight gain. It is not unusual for someone recovering from an eating disorder to experience a panic attack after eating something they previously avoided for years. Mental health support that includes trauma-informed therapy is crucial in navigating this complex relationship between food and anxiety.

3. How do social and cultural factors influence the experience of food-induced anxiety? Social pressures and cultural expectations can significantly shape one’s emotional responses to food. In environments where dieting, food labeling, and restrictive eating are normalized, individuals may internalize fear-based narratives around eating. These cultural messages can create anticipatory stress about meals, particularly when dining with others or consuming foods perceived as “unhealthy.” This social tension can turn into food anxiety over time, especially when the individual feels judged or scrutinized for their choices. For those already prone to anxiety after eating, the added burden of cultural expectations can intensify both emotional and physiological responses.

4. Can food-induced anxiety be mistaken for a food allergy or intolerance? Yes, it is not uncommon for food-induced anxiety to mimic or be misinterpreted as a food allergy or intolerance. Both conditions can produce overlapping symptoms, such as nausea, bloating, heart palpitations, or dizziness. However, while a true intolerance or allergy involves a physiological reaction to specific compounds in food, food anxiety can trigger similar sensations purely through the body’s stress response. This confusion can lead individuals to unnecessarily restrict their diets, which may further entrench food anxiety and reduce dietary diversity. Working with both a medical provider and a therapist can help distinguish between genuine food sensitivities and psychosomatic reactions rooted in anxiety.

5. Are there specific personality traits that increase susceptibility to food anxiety? Research suggests that individuals with high levels of neuroticism, perfectionism, or obsessive-compulsive tendencies may be more vulnerable to developing food anxiety. These traits can lead to increased vigilance around food choices, heightened sensitivity to bodily sensations, and a tendency to catastrophize minor symptoms. For example, someone with perfectionist tendencies might interpret a slight stomach discomfort as evidence of having eaten the “wrong” food, which could spiral into a full-blown panic attack after eating. Recognizing how personality traits interact with food-related stress can help tailor therapeutic interventions that address both cognitive patterns and emotional triggers.

6. How does intermittent fasting affect food-induced anxiety in some individuals? While intermittent fasting may have metabolic benefits for some, it can also backfire for individuals prone to food-induced anxiety. Skipping meals or eating within narrow time windows may destabilize blood sugar and cortisol levels, particularly in those with preexisting anxiety or adrenal sensitivity. The result can be increased irritability, restlessness, and even panic episodes after breaking the fast. For some people, the pressure to “eat perfectly” within a restricted timeframe also introduces unnecessary stress, which can heighten food anxiety over time. A more balanced approach that prioritizes consistency, nourishment, and flexibility may be more supportive for mental wellness in these cases.

7. Can a panic attack after eating occur without any conscious food fear? Yes, some individuals experience a panic attack after eating without any clear emotional trigger or conscious food fear. This often happens due to physiological mechanisms such as reactive hypoglycemia, histamine intolerance, or vagus nerve activation during digestion. In such cases, the person may suddenly feel dizzy, flushed, or short of breath after eating, leading to a panic response with no obvious psychological cause. The unpredictability of these episodes can create secondary food anxiety, as individuals begin to fear the act of eating itself. Identifying and addressing the physiological root cause is essential in breaking this cycle.

8. Are there emerging therapies that show promise for treating food-induced anxiety? Yes, several integrative and emerging therapies are gaining traction in the treatment of food-induced anxiety. One example is gut-directed hypnotherapy, which uses guided visualization techniques to calm both gastrointestinal and psychological symptoms simultaneously. Another promising approach is neurofeedback, which trains individuals to modulate brainwave activity to improve emotional regulation and reduce anxiety responses. Additionally, functional medicine protocols that target gut health, inflammation, and micronutrient optimization are being used more frequently to support those dealing with chronic food anxiety. These newer modalities can offer hope, especially for individuals who have not responded well to traditional therapy alone.

9. What role does anticipatory anxiety play in panic attacks after eating? Anticipatory anxiety can be a powerful driver of panic attacks after eating, especially in individuals who have previously experienced distress following meals. The mere expectation of a negative outcome—such as bloating, pain, or embarrassment—can activate the sympathetic nervous system before a bite is even taken. This preemptive stress creates a self-fulfilling prophecy: the body enters a fight-or-flight state, digestion slows, and physical symptoms intensify. Over time, this can condition the brain to associate eating with fear, compounding food-induced anxiety. Cognitive-behavioral strategies that challenge catastrophic thinking and promote relaxation before meals can be highly effective in breaking this pattern.

10. How can someone support a loved one experiencing food anxiety or anxiety after eating? Supporting someone with food anxiety requires empathy, patience, and a nonjudgmental approach. Rather than focusing solely on their food choices, it’s more helpful to inquire about how they’re feeling and what support they might need in that moment. Avoid making comments about portion sizes, nutritional value, or dietary habits, as these can unintentionally fuel anxiety. If a loved one frequently experiences a panic attack after eating, encourage them to seek professional help, but refrain from pressuring or pathologizing their behavior. Creating a calm, supportive environment where meals are associated with safety and connection can go a long way in reducing food-induced anxiety over time.

Moving Forward with Confidence and Clarity

Understanding the connection between food and anxiety represents a meaningful step toward greater self-awareness and well-being. For those who have experienced food-induced anxiety or a panic attack after eating, it is validating to know that these reactions are not imaginary or irrational—they are rooted in a dynamic interplay between biology, psychology, and environment.

By identifying food triggers, supporting gut health, stabilizing blood sugar, and addressing underlying emotional patterns, individuals can begin to reclaim their relationship with food. It is not always a linear journey, and setbacks are to be expected. However, with the right support, knowledge, and self-compassion, it is entirely possible to find relief and create a nourishing, anxiety-reducing lifestyle.

Rather than viewing food as a potential threat, it can become a powerful ally in mental health. Through mindful eating, strategic nutrition, and therapeutic support, those who struggle with food anxiety can develop a sense of peace around meals and reduce the likelihood of experiencing anxiety after eating. This holistic approach offers hope, clarity, and a path toward greater freedom—not just at the dinner table, but in daily life as a whole.

Was this article helpful? Don’t let it stop with you. Share it right now with someone who needs to see it—whether it’s a friend, a colleague, or your whole network. And if staying ahead on this topic matters to you, subscribe to this publication for the most up-to-date information. You’ll get the latest insights delivered straight to you—no searching, no missing out.

Further Reading:

How to Cope with Anxiety About Food