A Deeper Look at Eating Behaviors and Mental Wellness

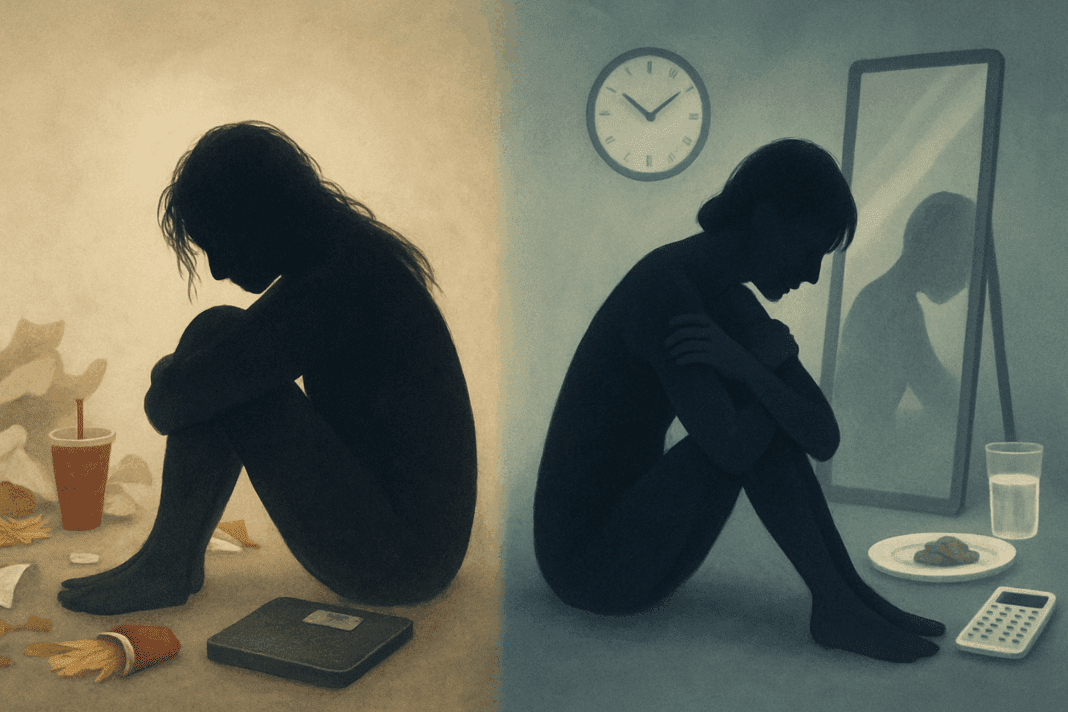

In today’s health-conscious society, conversations surrounding food, nutrition, and mental health are growing more nuanced. Amid this dialogue, terms like “disordered eating” and “eating disorder” are often used interchangeably, leading to confusion about their true meanings and implications. Yet, understanding the distinction between disordered eating vs eating disorder is essential for anyone seeking to foster a healthier relationship with food and body image. The differences carry significant weight, both clinically and culturally, and misinterpretation can delay vital interventions.

You may also like: How to Stop Emotional Eating and Regain Control: Mindful Nutrition Strategies That Support a Healthier Lifestyle

Clarifying these definitions is not just a matter of semantics. It is a matter of public health. While one may describe a set of unhealthy patterns that could lead to greater problems, the other defines diagnosable psychiatric conditions requiring specialized treatment. As we delve into the disordered eating definition and its contrast with clinically recognized eating disorders, we aim to equip readers with both insight and clarity. This understanding can promote timely action, empower informed self-reflection, and support mental and nutritional wellness within a broader lifestyle context.

Defining Disordered Eating: A Pattern Worth Watching

Disordered eating refers to a spectrum of irregular eating behaviors that, while not meeting the criteria for a full-fledged eating disorder, still raise red flags. This can include chronic dieting, compulsive eating, food restriction for non-medical reasons, or using food as a coping mechanism for stress or emotional discomfort. Unlike an eating disorder, disordered eating is not classified as a mental illness, but that doesn’t make it benign. Over time, these behaviors can spiral into more severe forms of psychological and physical distress.

The disordered eating definition emphasizes its subtler, often socially normalized characteristics. For example, skipping meals to “save calories” for later or experiencing guilt after eating are behaviors that might fly under the radar. In many circles, such actions are even praised as signs of discipline or commitment to fitness. Yet beneath this praise lies a fragile framework that can collapse under the weight of emotional instability or environmental stress.

Furthermore, disordered eating is not confined to a particular demographic. College students, athletes, and working professionals alike may engage in these behaviors due to pressure, stress, or societal expectations. The danger is that the normalization of such patterns delays recognition and treatment. While disordered eating may not be classified as a medical condition, it remains a significant concern because of its potential to evolve into a full-blown eating disorder if left unaddressed.

Understanding the Diagnostic Criteria for Eating Disorders

Unlike disordered eating, eating disorders are diagnosable mental health conditions with specific criteria outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). The most well-known include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder. Each is characterized by a distinct set of behaviors and psychological drivers, and their impact can be severe, affecting both physical health and psychological stability.

For instance, anorexia nervosa is marked by intense fear of gaining weight and a distorted body image, leading to extreme restriction of food intake. Bulimia involves cycles of bingeing and purging, often accompanied by feelings of shame and lack of control. Binge-eating disorder, now recognized as a standalone diagnosis, involves recurrent episodes of eating large quantities of food, usually quickly and to the point of discomfort, without the compensatory behaviors seen in bulimia.

These conditions carry serious health risks, ranging from electrolyte imbalances and gastrointestinal distress to cardiovascular complications and even death. Early diagnosis and intervention are critical. By recognizing the severity and specificity of eating disorders, we distinguish them from the broader category of disordered eating. This distinction is essential for providing the appropriate level of care and support.

How Cultural Norms Blur the Lines Between Health and Harm

Cultural influences play a powerful role in shaping our perceptions of food and body image, often muddling the lines between disordered eating vs eating disorder. From diet culture to fitness trends and social media-driven body ideals, individuals are constantly exposed to messages that can normalize unhealthy behaviors. What begins as an attempt to “eat clean” or “get fit” can easily escalate into obsessive routines and distorted self-evaluation.

Modern society tends to glorify control, discipline, and thinness, equating these traits with success and worthiness. This societal validation of restrictive behavior can obscure early signs of trouble. For example, someone who refuses entire food groups, logs every bite, or becomes anxious when deviating from a meal plan might be praised for their dedication rather than encouraged to examine the psychological implications behind their habits.

In this cultural context, the disordered eating definition becomes particularly significant. It allows us to challenge the subtle but harmful behaviors that often go unchecked. It also opens the door to discussing how these patterns differ from eating disorders in terms of intent, severity, and impact. Recognizing the cultural forces at play helps shift the narrative from shame to understanding and opens opportunities for education and intervention.

Psychological Triggers and Emotional Underpinnings

The psychological landscape of eating behaviors is complex and deeply intertwined with emotional well-being. Disordered eating often stems from attempts to manage emotions such as anxiety, depression, loneliness, or a sense of lack of control. Food becomes a tool for emotional regulation, whether through restriction, overindulgence, or obsessive control. These behaviors may serve as a coping strategy in the absence of healthier emotional outlets.

In contrast, eating disorders typically involve more entrenched psychological drivers and may be rooted in trauma, perfectionism, low self-esteem, or a history of emotional neglect. These deeper psychological layers require a more structured and intensive approach to treatment, including therapy, medical monitoring, and often nutritional rehabilitation. By understanding these distinctions, we can begin to see how disordered eating may serve as a warning signal rather than an endpoint.

Importantly, both disordered eating and eating disorders reflect the profound connection between mind and body. They remind us that nourishment is not merely about calories but also about identity, emotion, and lived experience. The journey to healing often begins with acknowledging this interplay and seeking support that addresses both psychological and nutritional needs.

Health Consequences That Often Go Unnoticed

While the physical toll of eating disorders is well-documented, the health consequences of disordered eating are frequently overlooked. Irregular meal patterns, chronic under-eating, or cycles of bingeing can result in nutritional deficiencies, gastrointestinal issues, fatigue, impaired concentration, and weakened immunity. These symptoms are often dismissed or misattributed to other causes, delaying appropriate care.

Even in the absence of dramatic weight changes, disordered eating can significantly impact metabolic health, hormonal balance, and overall vitality. For instance, individuals who habitually skip meals may experience blood sugar instability, irritability, and difficulty focusing. Over time, this can contribute to mood swings, anxiety, and burnout—factors that further entrench unhealthy eating behaviors.

By bringing attention to these less-visible effects, we emphasize the importance of addressing disordered eating early. It is not a “milder” form of a problem to be ignored but a legitimate concern with real physiological consequences. Recognizing the disordered eating definition as more than just a set of quirky habits reframes it as a public health issue that deserves the same seriousness as other medical conditions.

Barriers to Recognition and Treatment

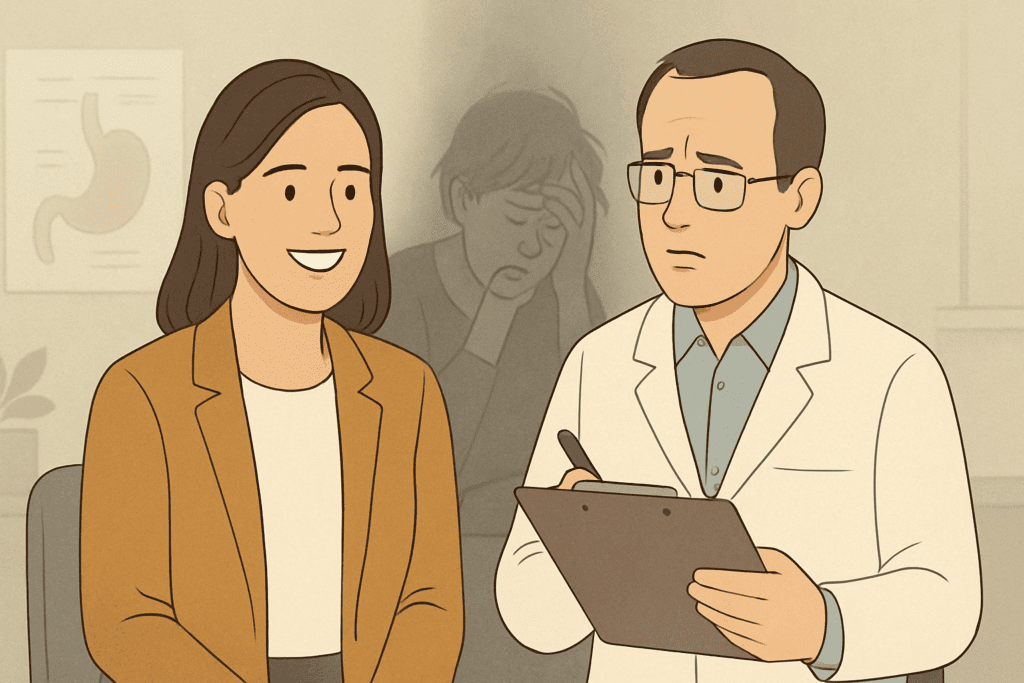

One of the greatest challenges in differentiating disordered eating vs eating disorder is the invisibility of early symptoms and the reluctance to seek help. Many individuals do not believe their behaviors are serious enough to warrant intervention, especially if they do not match the stereotypical image of an eating disorder. Others may fear judgment, stigma, or loss of perceived control over their health practices.

Healthcare providers may also miss early warning signs, particularly if a patient’s weight appears “normal” or if the individual is otherwise high-functioning. This underscores the need for better education and awareness among both patients and professionals. It also calls for a more nuanced approach to assessment that considers psychological and behavioral indicators beyond physical appearance.

The stigma associated with mental health concerns further complicates help-seeking behavior. When food behaviors are intertwined with identity, perfectionism, or social belonging, individuals may be reluctant to let go, even when those behaviors become harmful. Addressing these psychological barriers requires compassionate dialogue, community support, and culturally sensitive care models.

When and How to Seek Help

Recognizing when to seek help is a pivotal step in addressing disordered eating or progressing eating disorders. While disordered eating may not be a formal diagnosis, its persistence and emotional toll should not be underestimated. If thoughts about food, body image, or eating habits begin to interfere with daily life, relationships, or emotional well-being, professional support should be considered.

Therapists specializing in eating behaviors can offer cognitive-behavioral interventions, mindfulness techniques, and trauma-informed care. Registered dietitians with experience in disordered eating can help re-establish balanced eating patterns without resorting to restrictive rules or diets. Support groups, online resources, and educational platforms can also provide community and encouragement during the recovery journey.

For those diagnosed with an eating disorder, a more comprehensive treatment plan may involve a multidisciplinary team, including medical doctors, psychologists, dietitians, and psychiatric specialists. Early intervention is key; outcomes improve dramatically when treatment begins before the disorder becomes deeply entrenched.

Whether one identifies with the disordered eating definition or recognizes the symptoms of a diagnosable eating disorder, taking the step to seek help is a powerful act of self-respect. Recovery is not linear, and support systems play an essential role in maintaining progress and preventing relapse. Every effort toward healing counts, and no concern is too small to merit compassionate attention.

Supporting Mental Wellness Through Mindful Eating Practices

One proactive approach to preventing disordered eating patterns is to cultivate mindful eating and nutrition habits. Mindful eating involves tuning into internal cues of hunger and fullness, savoring food without distraction, and letting go of judgmental thoughts about eating. This practice can promote a healthier, more intuitive relationship with food and reduce the risk of falling into disordered patterns.

Mindful eating is not about perfection but about presence. It allows individuals to reconnect with their bodies and detach from rigid food rules or guilt-laden narratives. By focusing on nourishment rather than control, individuals can shift from a mindset of deprivation to one of abundance and self-care.

Educating individuals about the difference between disordered eating vs eating disorder in accessible, non-judgmental ways can also reduce stigma and increase self-awareness. Promoting balanced meals, regular eating patterns, and emotional regulation strategies can create an environment where healthy eating behaviors flourish.

Holistic approaches to wellness that integrate mental health support, nutritional guidance, and stress management offer sustainable alternatives to diet culture. When individuals feel empowered rather than shamed, they are more likely to adopt practices that nurture long-term health and resilience.

Frequently Asked Questions: Disordered Eating vs Eating Disorder

What role does social media play in influencing disordered eating behaviors? Social media platforms often promote curated images and narratives that idealize certain body types and lifestyles, which can subtly reinforce harmful eating patterns. The comparison culture fueled by influencers and fitness trends may increase anxiety around food and body image, especially in young adults. Unlike clinical eating disorders, disordered eating often arises in this gray area of normalized yet emotionally damaging behavior. When it comes to understanding disordered eating vs eating disorder, social media rarely highlights the distinction, making it harder for users to recognize when their habits are veering into unhealthy territory. This underscores the importance of media literacy and the need to follow content creators who promote body positivity and balanced nutrition rather than unrealistic ideals.

Can disordered eating be situational or temporary? Yes, disordered eating can sometimes be triggered by life transitions, emotional upheaval, or temporary stress. For instance, someone experiencing academic pressure, a breakup, or a job loss might unintentionally fall into irregular eating habits like emotional overeating or skipping meals. While these behaviors may not qualify as an eating disorder, the disordered eating definition allows us to identify them as concerning even if they’re short-term. Recognizing these patterns early helps prevent them from solidifying into chronic issues. The key is paying attention to whether these behaviors persist beyond the triggering situation and begin affecting emotional and physical well-being.

How does perfectionism contribute to both disordered eating and eating disorders? Perfectionism is a common psychological trait among individuals struggling with both disordered eating and clinically defined eating disorders. The desire to control every aspect of food intake, weight, or physical appearance can spiral into harmful routines. For someone with disordered eating, perfectionism might manifest as rigid meal planning or compulsive calorie counting, while for others, it may escalate into an eating disorder requiring medical intervention. Understanding disordered eating vs eating disorder in this context reveals how underlying traits like perfectionism can exist on a spectrum, increasing vulnerability across both categories. It also suggests the importance of addressing perfectionistic thinking in therapy to promote long-term recovery.

Is it possible to exhibit signs of both disordered eating and an eating disorder at the same time? In many cases, the line between the two is not clearly drawn, and individuals may exhibit overlapping behaviors. Someone might not meet the full diagnostic criteria for an eating disorder yet experience episodes of binge eating, food guilt, and social withdrawal around meals. This blending of symptoms reinforces the importance of not relying solely on diagnostic labels when assessing someone’s relationship with food. While the disordered eating definition captures the subtleties of these patterns, early intervention is essential regardless of the classification. Health professionals often assess the frequency, duration, and emotional impact of behaviors to determine the most appropriate form of care.

How does the workplace environment affect eating behaviors in adults? Work-related stress, long hours, and limited access to nutritious meals can all influence the development of disordered eating patterns among professionals. Skipping meals, eating at odd hours, or relying heavily on convenience foods are often normalized in fast-paced work cultures. These behaviors may not constitute a diagnosable eating disorder, but they reflect the disordered eating definition in a lifestyle context. Over time, these habits can disrupt metabolic rhythms and contribute to anxiety or burnout. Employers and wellness programs can play a significant role in promoting healthier habits by supporting structured meal breaks and nutrition education.

How can family dynamics shape eating behaviors during childhood and adolescence? Family influences can deeply shape a child’s relationship with food, often laying the foundation for either healthy or disordered eating habits. Parental attitudes toward dieting, body image, and emotional regulation can all transmit beliefs that influence how a child views food. For example, a home where weight is frequently discussed or where emotional support is lacking may encourage a child to use food as a coping mechanism. In these cases, disordered eating may develop without ever progressing into an eating disorder, though the risk remains. The difference between disordered eating vs eating disorder in these early years often lies in the severity of the emotional and behavioral patterns that take root.

Are men affected by disordered eating, and how does it differ from women’s experiences? Men do experience disordered eating, though their symptoms are often underreported and misunderstood. Cultural expectations around masculinity may discourage men from acknowledging food-related anxieties or seeking help. In men, disordered eating might center more on body composition, such as an obsessive focus on leanness or muscle gain rather than weight loss. Understanding disordered eating vs eating disorder also involves recognizing gender-specific expressions, which may differ from more widely studied female patterns. Encouraging open conversations and gender-sensitive screening tools can help bridge the gap in awareness and treatment.

What emerging therapies are being explored for early-stage disordered eating? Several innovative approaches are showing promise in addressing disordered eating before it evolves into an eating disorder. Somatic therapies, such as body-based mindfulness practices, help individuals reconnect with internal cues like hunger and fullness. Additionally, digital interventions, including app-based journaling and virtual cognitive-behavioral therapy, provide accessible tools for self-monitoring and reflection. These emerging treatments are especially useful in the gray zone where someone may not meet criteria for an eating disorder but still fits the disordered eating definition. They emphasize early prevention and can reduce the long-term emotional and physical toll of disordered patterns.

Can nutritional education alone correct disordered eating habits? While nutritional education is a vital component of healing, it is rarely sufficient on its own. Disordered eating behaviors often stem from psychological, emotional, or social stressors that go beyond basic knowledge about healthy foods. For example, someone may know what constitutes a balanced meal but still struggle with guilt or anxiety around eating due to unresolved trauma. Addressing disordered eating vs eating disorder effectively requires a multidisciplinary approach that includes therapy, emotional support, and nutritional guidance. Education can empower individuals to make informed choices, but sustainable change usually involves addressing the underlying beliefs driving those choices.

What is the long-term impact of untreated disordered eating? Even when disordered eating does not escalate to a full-blown eating disorder, its long-term consequences can be significant. Chronic nutritional imbalances may lead to fatigue, weakened immunity, hormonal disruptions, or gastrointestinal issues. Mentally, persistent guilt, anxiety, and preoccupation with food can erode self-esteem and contribute to depression. Recognizing the disordered eating definition helps highlight the importance of early detection and ongoing support to prevent long-term complications. In the disordered eating vs eating disorder conversation, this underscores the idea that both require attention, even if their severity differs.

Conclusion: Reclaiming Food Freedom and Emotional Balance

Understanding the nuanced differences between disordered eating vs eating disorder is not only an exercise in medical literacy—it is a step toward reclaiming food freedom and emotional balance. While disordered eating may appear less severe, its long-term effects can be just as profound if left unchecked. Recognizing the disordered eating definition and acknowledging its presence in our culture is essential for early intervention and prevention.

By shedding light on the psychological, physiological, and cultural aspects of eating behaviors, we create space for more informed, compassionate conversations. These conversations empower individuals to reflect, seek help, and ultimately heal. Whether through mindful eating, professional support, or community connection, there are many paths to recovery—and all begin with awareness.

In a world saturated with mixed messages about food and body image, clarity is a form of self-care. When we learn to identify the signs, understand the differences, and seek appropriate support, we move closer to a healthier, more connected way of living. The journey starts with knowledge—and every step forward matters.

Was this article helpful? Don’t let it stop with you. Share it right now with someone who needs to see it—whether it’s a friend, a colleague, or your whole network. And if staying ahead on this topic matters to you, subscribe to this publication for the most up-to-date information. You’ll get the latest insights delivered straight to you—no searching, no missing out.

Further Reading:

The Difference Between Disordered Eating and Eating Disorders