Understanding the Foundation: Aerobic Activity Definition and Core Concepts

When young adults begin to explore options for improving their fitness and health, terms like “aerobic” and “cardiovascular” often emerge interchangeably. Yet while they are closely related, understanding the aerobic activity definition is key to grasping the distinctions and optimizing training outcomes. Aerobic exercise is defined as any form of physical activity that relies on the presence of oxygen to generate energy. This process engages large muscle groups over an extended period and is designed to improve the efficiency of the body’s cardiovascular and respiratory systems. It includes familiar activities like running, cycling, swimming, and brisk walking. Cardiovascular exercise, often shortened to cardio, shares significant overlap but technically encompasses any activity that elevates the heart rate and strengthens the heart, including both aerobic and anaerobic exercises.

You may also like: How to Increase Stamina and Endurance Naturally: Smart Training Tips and Nutrition Habits That Support Cardiovascular Fitness

This distinction is important because the aerobic activity definition emphasizes sustained, rhythmic movements that primarily improve endurance and oxygen uptake. In contrast, cardio is a broader term that may include short, intense anaerobic bursts, such as sprinting or high-intensity interval training (HIIT), depending on the activity’s structure. For early adulthood fitness planning, grasping these nuances allows for more intentional program design. This level of clarity is critical for achieving specific outcomes, such as enhancing cardiorespiratory function or building muscular endurance. The terminology may seem nuanced, but knowing the difference between aerobic vs. cardiovascular exercise helps young adults make informed, strategic fitness choices.

Do Adults Need Aerobic Exercise or Anaerobic Exercise? A Balanced Approach to Endurance and Power

The question of whether adults need aerobic exercise or anaerobic exercise is not merely academic—it is a crucial decision that shapes fitness outcomes and long-term health. Both exercise types offer unique physiological benefits, and choosing one over the other often depends on individual goals. Aerobic exercise, such as long-distance running or cycling, improves heart health, boosts oxygen delivery, and builds endurance. Anaerobic exercise, on the other hand, includes short bursts of high-intensity activity such as weightlifting or sprinting, which primarily improve muscle strength, speed, and power.

While it may be tempting to focus solely on one type, especially for performance athletes or aesthetic goals, early adulthood is the ideal time to develop a foundation that includes both. This is when the body is typically most responsive to training adaptations, offering an optimal window for long-term conditioning. Combining aerobic conditioning with anaerobic bursts helps create a more comprehensive fitness profile. For example, a young adult training for a marathon can benefit from anaerobic sprints to improve lactate threshold, while a powerlifter can integrate aerobic sessions to enhance recovery and cardiovascular health.

This integrated approach is especially relevant given the growing body of research suggesting that all forms of aerobic activity can promote cardiorespiratory fitness while also supporting metabolic health, cognitive function, and emotional well-being. Choosing between the two should not be an either/or proposition but rather a question of how to blend them for maximum performance, longevity, and resilience. Therefore, rather than asking if early adulthood should do aerobic or anaerobic exercise, a more useful inquiry is how to effectively combine them.

Benefits of Aerobic Activity: More Than Just Endurance

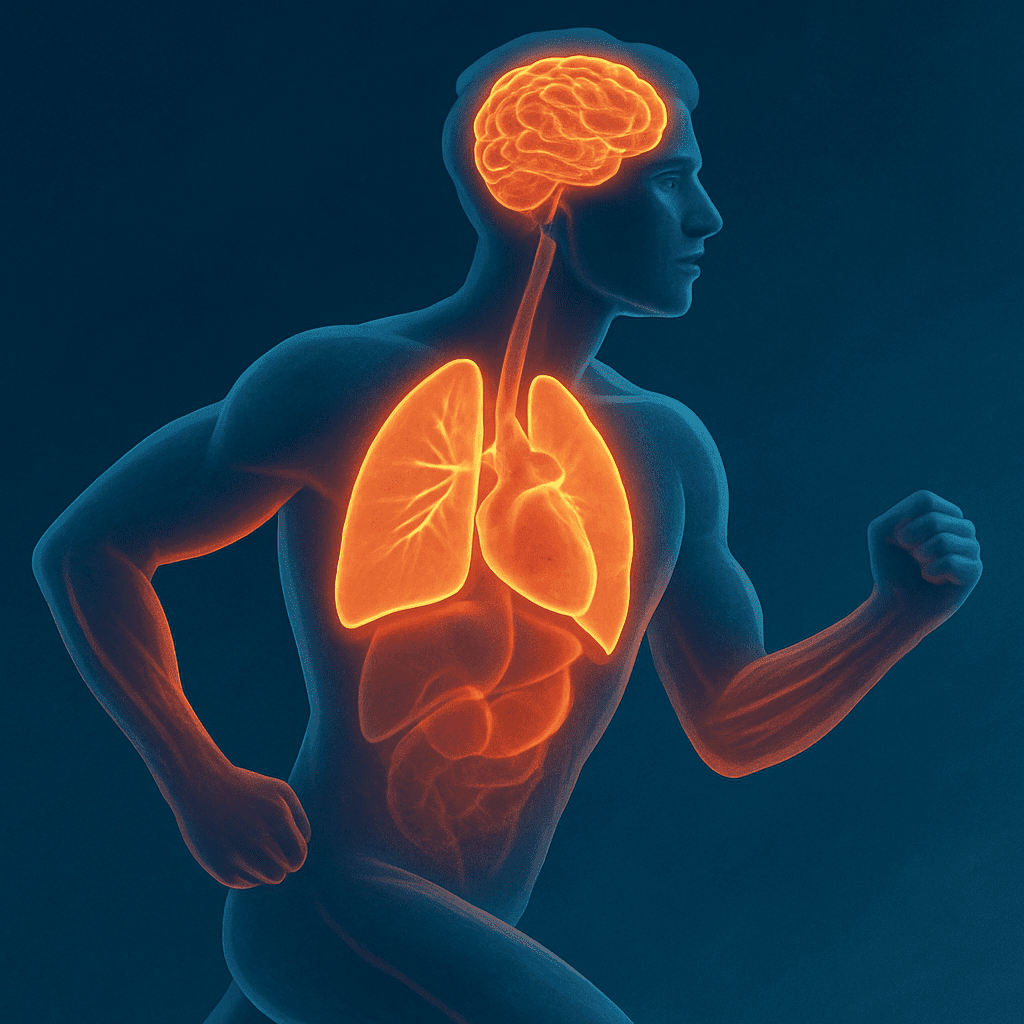

Too often, aerobic exercise is narrowly associated with weight loss or stamina-building. However, the benefits of aerobic activity extend far beyond the obvious. Regular aerobic training improves the body’s ability to transport and utilize oxygen efficiently, reducing resting heart rate and improving circulation. This leads to more efficient energy use during both exercise and daily activities. The enhanced oxygen delivery also supports brain function, potentially improving memory, focus, and overall mood through increased production of neurotrophic factors.

Furthermore, all forms of aerobic activity can promote cardiorespiratory fitness, which in turn reduces the risk of chronic diseases such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and certain cancers. For young adults, this foundational fitness sets the stage for a longer, healthier life with fewer medical complications. Another often-overlooked benefit is its effect on hormonal regulation. Aerobic activity can reduce stress hormone levels, including cortisol, while promoting the release of endorphins and other mood-enhancing neurotransmitters.

Beyond internal changes, aerobic activity also cultivates discipline, routine, and resilience. Whether training for a half-marathon or simply committing to daily brisk walks, consistency in aerobic training fosters a mindset of self-mastery. And from a public health perspective, early adulthood is the ideal time to form habits that will significantly reduce the burden of chronic illness later in life. Ultimately, the benefits of aerobic activity transcend mere physical outcomes—they establish a holistic framework for wellness.

Aerobic Conditioning: Building a Stronger, More Efficient Body

Aerobic conditioning refers to the systematic improvement of the body’s ability to perform sustained physical activity over time. This involves enhancing the function of the heart, lungs, blood vessels, and muscles to work together more efficiently. Young adults in particular benefit from aerobic conditioning because their bodies are still highly adaptable, capable of making dramatic gains in endurance, oxygen uptake, and muscular efficiency with the right training stimulus.

Effective aerobic conditioning results from progressively challenging the cardiovascular system. Activities such as distance running, cycling, and swimming—performed at moderate intensity for extended periods—help increase mitochondrial density and improve the muscles’ ability to utilize oxygen. Over time, these adaptations allow individuals to perform the same work with less perceived effort. This physiological economy is essential not just for athletes, but for anyone seeking to improve their quality of life through increased physical capability and reduced fatigue.

Aerobic conditioning also enhances recovery from both aerobic and anaerobic efforts. For example, a well-conditioned athlete will recover more quickly between sprints or weightlifting sets due to improved blood flow and oxygen delivery. Importantly, conditioning need not be monotonous. Modern training methodologies incorporate varied approaches like tempo runs, long slow distance training, and low-intensity steady-state cardio (LISS), allowing for creativity and personalization. These strategies ensure that aerobic conditioning remains both effective and engaging for young adults committed to long-term fitness development.

Does Aerobic Exercise Help Build Stronger Muscles? Rethinking the Role of Endurance Training

It’s a common misconception that aerobic exercise is only useful for weight loss or cardiovascular health, with little to no role in muscular development. However, when asking whether aerobic exercise helps build stronger muscles, the answer is more nuanced. While it’s true that aerobic training doesn’t typically produce the hypertrophy associated with heavy resistance training, it does enhance muscular endurance and efficiency, which are critical components of strength in real-world settings.

In endurance sports and functional fitness, strength is not solely measured by how much weight one can lift, but by the ability of muscles to perform consistently over time. Aerobic exercise stimulates slow-twitch muscle fibers, which are more fatigue-resistant and essential for prolonged activity. This makes aerobic training invaluable for improving movement quality, reducing the risk of injury, and supporting joint stability. For example, long-distance runners develop robust lower body musculature adapted for endurance, while swimmers gain upper-body strength and flexibility through repetitive motion and resistance.

Moreover, aerobic training supports muscle health by improving capillary density and nutrient delivery, ensuring that working muscles receive the oxygen and fuel they need for sustained performance. It also enhances the removal of metabolic byproducts, contributing to quicker recovery. Therefore, while aerobic exercise may not significantly increase muscle size, it undeniably contributes to muscular strength and integrity in ways that support overall athleticism and longevity. Understanding this broadens the definition of strength beyond aesthetics to include resilience, durability, and functional capacity.

Aerobic vs. Cardiovascular Exercise: Clearing Up the Confusion for Optimal Results

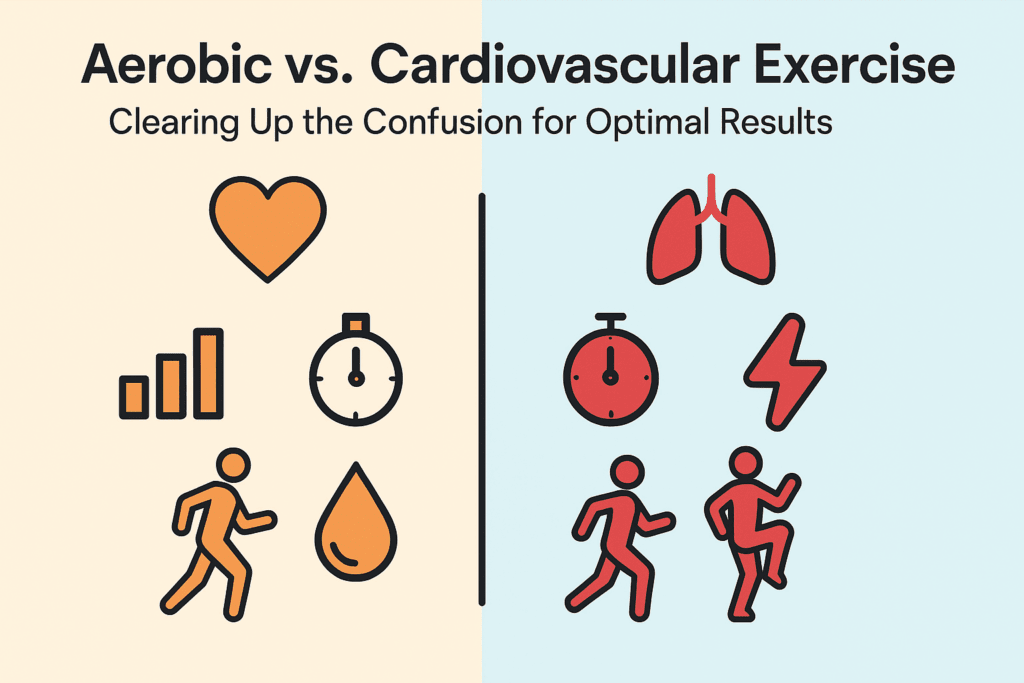

The terms aerobic and cardiovascular exercise are often used interchangeably, creating confusion about how best to train for specific fitness goals. Although the overlap is substantial, understanding the difference between aerobic vs. cardiovascular exercise helps clarify the intended outcomes of various workouts. As established earlier, aerobic exercise specifically refers to prolonged activities that rely on oxygen-based energy production. Cardiovascular exercise, in contrast, is a broader category that includes both aerobic and anaerobic forms, provided they significantly elevate heart rate.

For young adults focused on endurance and stamina training, aerobic exercise is a cornerstone, promoting adaptations in oxygen delivery and utilization. This includes classic modalities like steady-state running or cycling at a moderate intensity. Cardiovascular training, however, can also include HIIT workouts that intersperse intense anaerobic bursts with recovery periods, challenging both aerobic and anaerobic systems. These sessions are particularly effective for improving overall conditioning and burning calories efficiently, but they may not provide the same foundational endurance benefits as traditional aerobic workouts.

Selecting between these training styles depends on one’s specific goals. For those aiming to improve cardiorespiratory fitness, all forms of aerobic activity can promote meaningful adaptations. On the other hand, if the goal is to enhance metabolic conditioning or peak power output, integrating anaerobic components into a cardiovascular framework may be more effective. In practice, the most successful training regimens balance both modalities, capitalizing on the strengths of each. This nuanced understanding enables young adults to move beyond vague fitness goals toward targeted, evidence-based strategies.

Should Early Adulthood Do Aerobic or Anaerobic Exercise? Personalized Training for a Critical Life Stage

The early adult years represent a critical window for establishing lifelong fitness habits, making it essential to address the question: should early adulthood do aerobic or anaerobic exercise? The answer is both—strategically and intentionally. This life stage offers peak physical resilience, faster recovery, and enhanced adaptive capacity, all of which are ideal conditions for exploring diverse exercise modalities.

Aerobic exercise lays the groundwork for long-term health by strengthening the heart, improving lung function, and supporting metabolic efficiency. These benefits are crucial for maintaining energy, mental clarity, and emotional balance during a time often characterized by academic and career pressures. Anaerobic exercise complements this foundation by building muscular strength, enhancing athletic performance, and boosting metabolism. For example, resistance training and sprinting not only improve body composition but also support bone density and functional strength, reducing the risk of injury over time.

By integrating both forms of exercise, early adults can create a resilient, adaptable physique capable of meeting a wide range of physical and psychological demands. A week might include aerobic runs, cycling sessions, and anaerobic strength circuits, creating a dynamic training schedule that targets multiple systems. This personalized blend ensures that fitness is sustainable, engaging, and effective. Far from being a binary choice, the decision about whether to do aerobic or anaerobic exercise in early adulthood should focus on developing a lifelong relationship with movement that evolves with individual needs and goals.

Frequently Asked Questions: Aerobic vs. Cardiovascular Exercise for Young Adults

1. How can young adults effectively transition from sedentary habits into an aerobic or cardiovascular training routine?

For young adults emerging from sedentary lifestyles, the transition into fitness doesn’t have to be overwhelming. One of the most accessible ways to begin is by integrating low-intensity forms of aerobic activity that require minimal equipment, such as walking, light cycling, or swimming. These options align well with the aerobic activity definition by focusing on sustained movement fueled by oxygen. Since all forms of aerobic activity can promote cardiorespiratory fitness, even short but consistent sessions yield noticeable health improvements. The key is to begin gradually and prioritize consistency, progressively increasing duration and intensity to enhance aerobic conditioning and minimize the risk of injury.

2. What psychological benefits are associated with aerobic conditioning in early adulthood?

Aerobic conditioning offers more than just physical transformation—it’s deeply linked to mental and emotional well-being, particularly during the often turbulent years of early adulthood. Regular aerobic sessions have been shown to reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety, improve sleep quality, and enhance cognitive performance. These psychological shifts are facilitated by neurochemical responses, including increased production of endorphins and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). By improving blood flow and oxygen delivery to the brain, aerobic activity also sharpens focus and reduces mental fatigue. This makes a compelling case for why early adulthood should not overlook the psychological benefits of aerobic exercise, especially as stress levels rise during academic, career, and social transitions.

3. In what ways do different sports blur the lines between aerobic vs cardiovascular exercise?

Many popular sports challenge the distinction between aerobic vs cardiovascular exercise because they incorporate both sustained and high-intensity intervals. Take soccer, for instance: players jog, sprint, and walk interchangeably throughout a match, engaging both aerobic and anaerobic systems. This hybrid approach enhances cardiovascular efficiency while reinforcing muscle strength and stamina. Although aerobic activity is often emphasized in endurance-based sports, most athletic disciplines require a blend of energy systems to optimize performance. This illustrates how the phrase aerobic exercise vs cardio oversimplifies what is, in reality, a highly integrated spectrum of physical effort.

4. Does aerobic exercise help build stronger muscles, or should that goal be left to anaerobic training?

While aerobic training doesn’t lead to muscle hypertrophy in the same way as anaerobic lifting routines, it plays a crucial role in developing muscular endurance, efficiency, and fatigue resistance. Activities like rowing, swimming, or distance running can contribute to strength development by recruiting stabilizing and postural muscles, particularly in the core and lower body. Additionally, aerobic exercise helps build stronger muscles indirectly by improving blood circulation and nutrient delivery during recovery. It enhances capillarization and mitochondrial density, making muscles more efficient and resilient. Therefore, it’s short-sighted to believe that only anaerobic training strengthens the body—there are multifaceted benefits of aerobic exercise for muscle health.

5. How do cultural and social factors influence the decision on whether early adulthood should do aerobic or anaerobic exercise?

Cultural expectations, peer influence, and even social media trends can play a major role in shaping preferences between aerobic and anaerobic exercise in early adulthood. For instance, weightlifting and bodybuilding often receive more visibility on platforms like Instagram, drawing young adults toward anaerobic training for aesthetic gains. However, group-oriented aerobic classes such as Zumba or spinning appeal to those seeking social connection, community, and stress relief. The decision of whether early adulthood should do aerobic or anaerobic exercise should therefore factor in not only physical goals but also personal values, cultural relevance, and long-term sustainability. Fitness must be enjoyable to become a lasting habit, and aligning exercise modes with one’s lifestyle and social circle enhances adherence.

6. What are some overlooked benefits of aerobic activity that extend beyond health and fitness?

In addition to enhancing cardiorespiratory and muscular function, the benefits of aerobic activity include life skills such as discipline, time management, and perseverance. Training regularly builds a sense of routine and personal accountability, traits that are transferable to academic and professional domains. Moreover, engaging in aerobic routines often increases environmental awareness; individuals may choose to bike or walk rather than drive, reducing their carbon footprint. These broader implications show that aerobic activity has the power to reshape habits, values, and priorities in meaningful ways. Thus, the benefits of aerobic exercise go well beyond physiological metrics and into realms of social, ethical, and behavioral development.

7. How does technology help optimize aerobic conditioning for young adults today?

Advancements in wearable technology, mobile apps, and biometric tracking have revolutionized how young adults approach aerobic conditioning. Devices like heart rate monitors and smartwatches offer real-time data on performance, allowing users to stay within optimal heart rate zones for aerobic development. These tools also help measure variables like VO2 max, sleep quality, and recovery time, making aerobic conditioning more personalized and data-driven. Many apps provide structured programs that gradually progress in intensity, helping young users avoid burnout and plateaus. This technological integration enhances the precision, engagement, and sustainability of aerobic training, especially for tech-savvy individuals who thrive on feedback and structure.

8. What role does aerobic exercise play in career and academic performance during early adulthood?

The benefits of aerobic activity directly support the cognitive and emotional stamina required for success in academic and early career settings. Enhanced oxygen delivery improves concentration, memory retention, and processing speed—key assets during long study sessions or demanding workdays. Aerobic conditioning also promotes stress resilience, which is crucial during high-pressure periods like finals or job interviews. Unlike quick fixes such as caffeine or energy drinks, aerobic activity provides a sustainable cognitive boost without side effects. When young adults prioritize aerobic exercise, they’re not just investing in fitness—they’re strengthening the mental and emotional foundation required for professional success.

9. What’s the practical difference between aerobic exercise vs cardio in everyday workout programming?

In everyday usage, the terms aerobic exercise vs cardio are often used interchangeably, but distinguishing them can help fine-tune workout design. Aerobic exercise refers to sustained, rhythmic movements like jogging or rowing that primarily use oxygen for energy, making them ideal for long-term endurance development. Cardiovascular training includes these but also embraces shorter, high-intensity bouts such as sprints or circuit workouts that may lean anaerobic. Understanding this difference helps young adults match their workouts with specific goals: improving heart health, burning fat, or enhancing performance. Thoughtfully alternating between traditional aerobic workouts and high-intensity cardio sessions offers a balanced training approach with broader benefits.

10. Do adults need aerobic exercise or anaerobic exercise more as they age, and how should early adulthood prepare for this?

While both forms of exercise remain valuable throughout life, the emphasis may shift slightly with age toward aerobic activity due to its protective effects on heart health, metabolism, and mobility. Early adulthood is the ideal time to build aerobic conditioning habits that will serve as a buffer against age-related decline. This stage of life is also perfect for developing muscular strength and bone density through anaerobic exercise, which helps prevent sarcopenia and osteoporosis later on. So, when evaluating whether adults need aerobic exercise or anaerobic exercise more, the answer depends on the life stage and health context—but early adulthood is where the dual foundation should be laid. A well-rounded regimen started in youth creates a fitness reserve that pays dividends in energy, independence, and resilience well into the later decades.

Conclusion: Embracing Aerobic and Cardiovascular Training for a Lifetime of Performance and Wellness

Understanding the differences—and intersections—between aerobic vs. cardiovascular exercise is more than a matter of semantics. For young adults committed to building endurance, enhancing stamina, and supporting overall health, the distinctions shape training effectiveness and sustainability. Aerobic activity, with its emphasis on prolonged, oxygen-fueled effort, provides foundational benefits such as improved heart function, respiratory capacity, and mental clarity. These benefits make it indispensable for establishing lifelong health and performance potential.

Meanwhile, cardiovascular training includes a broader range of movements that can be tailored to suit diverse goals, from fat loss to peak power output. Whether a workout leans more aerobic or incorporates anaerobic intensity, it has the potential to contribute to physical growth, mental resilience, and emotional well-being. Integrating both forms of movement creates a well-rounded, capable body that can adapt to life’s many challenges.

Rather than framing the conversation as aerobic exercise vs cardio or aerobic vs cardiovascular exercise, it is more productive to view these modalities as complementary tools. When young adults recognize that all forms of aerobic activity can promote cardiorespiratory fitness while also contributing to muscular strength and endurance, they are better positioned to design smart, personalized training plans. Ultimately, the decision of whether adults need aerobic exercise or anaerobic exercise becomes irrelevant in light of the greater truth: a healthy, high-performing life demands both.

By embracing this integrative approach, early adulthood becomes a launchpad for enduring health, optimal performance, and resilient vitality across the lifespan.

Was this article helpful? Don’t let it stop with you. Share it right now with someone who needs to see it—whether it’s a friend, a colleague, or your whole network. And if staying ahead on this topic matters to you, subscribe to this publication for the most up-to-date information. You’ll get the latest insights delivered straight to you—no searching, no missing out.

Further Reading:

Health-Related Fitness Measures for Youth: Cardiorespiratory Endurance

Aerobic vs anaerobic exercise training effects on the cardiovascular system