For many individuals seeking better cardiovascular health, a common question arises: how does exercise lower blood pressure? This inquiry is both timely and critical, as hypertension remains one of the most prevalent and preventable risk factors for heart disease, stroke, and premature death. Modern research continues to affirm the powerful role physical activity plays in regulating blood pressure levels, offering not only short-term relief but long-term vascular protection. Understanding the physiological mechanisms behind this benefit empowers individuals to make informed decisions about their exercise routines, ensuring they prioritize not just aesthetics or endurance, but also the silent yet essential work of blood pressure control.

You may also like: Smart Nutrition Choices for a Healthier Lifestyle: What to Know About Whole Grain Rice and Whole Wheat Rice

The Cardiovascular Connection: Why Exercise Helps Regulate Blood Pressure

To explore why exercise lowers blood pressure, one must first understand the dynamic nature of cardiovascular function. Blood pressure refers to the force exerted by circulating blood against arterial walls, and it fluctuates based on activity, stress, diet, and overall cardiovascular fitness. During physical activity, the heart beats faster and more efficiently, pumping blood with greater force to meet the body’s increased oxygen demands. Over time, regular cardiovascular exercise conditions the heart to work less strenuously at rest, reducing the overall strain on arterial walls.

This physiological adaptation leads to a drop in resting blood pressure, particularly for those with elevated levels. Exercise lowers blood pressure by enhancing endothelial function, which refers to the lining of the blood vessels. Healthy endothelium is flexible and responsive, allowing arteries to dilate more effectively and thus reduce resistance. In this way, the answer to how does exercise reduce blood pressure lies in improved vascular flexibility and efficiency. Moreover, exercise helps reduce sympathetic nervous system activity, which governs the “fight or flight” response. Lower sympathetic tone means fewer hormonal signals that constrict blood vessels, allowing for easier blood flow and lower pressure.

The Science of Physical Activity and Vascular Resistance

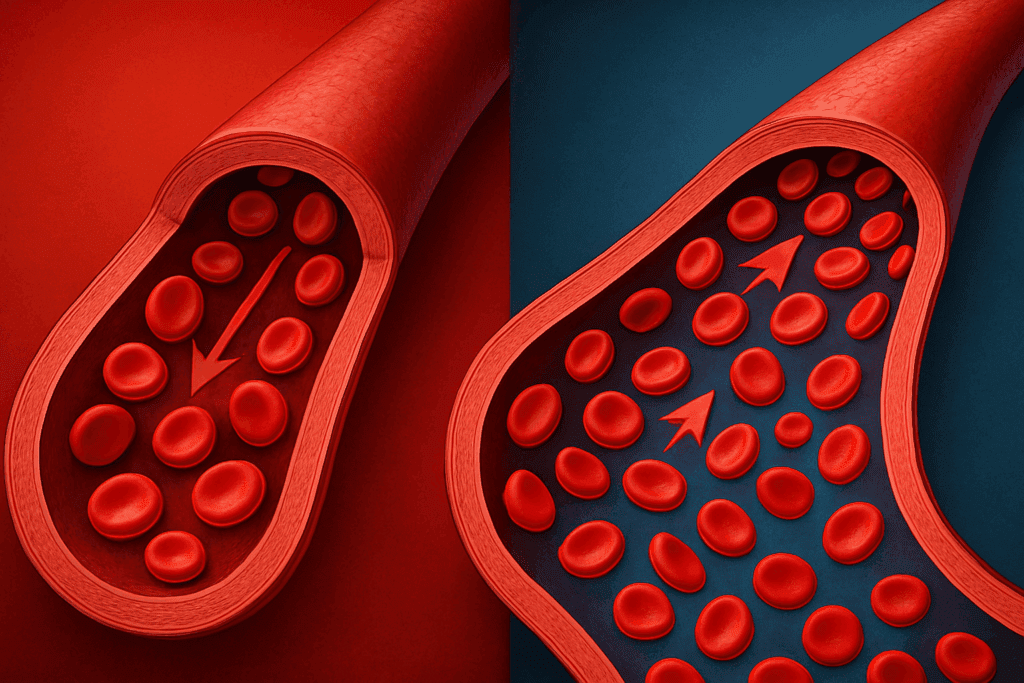

Delving deeper into how physical activity reduces blood pressure, one finds a compelling interplay between exercise and vascular resistance. Vascular resistance refers to the opposition blood encounters as it flows through the arteries. High resistance leads to elevated pressure, often a hallmark of chronic hypertension. Cardio reduces blood pressure by lowering this resistance through multiple mechanisms. Aerobic activity stimulates the release of nitric oxide, a powerful vasodilator that helps widen blood vessels and improve circulation.

Furthermore, exercise promotes angiogenesis, or the formation of new blood vessels. This increased vascular network reduces the load on existing arteries and allows blood to flow more freely, easing pressure on the heart and lowering systolic and diastolic readings. These processes explain why consistent cardio reduces blood pressure not only during the activity itself but also during rest and sleep. In fact, the long-term effects of physical activity can be comparable to some antihypertensive medications, especially when practiced regularly.

Why Cardiovascular Exercise Is Especially Effective

While resistance training, flexibility work, and mobility exercises all contribute to overall wellness, cardiovascular exercise stands out in its ability to manage hypertension. So, why does cardiovascular exercise lower blood pressure more effectively? The answer lies in its sustained impact on oxygen uptake, heart rate, and vascular remodeling. Activities such as brisk walking, jogging, swimming, and cycling elevate the heart rate over a prolonged period, promoting continuous vascular engagement.

This ongoing demand encourages the heart to become more efficient, increasing stroke volume—or the amount of blood pumped with each beat—while simultaneously reducing heart rate. Over time, the result is a heart that performs better under lower pressure, even when subjected to daily stressors. Because cardiovascular exercise also improves insulin sensitivity, it helps reduce the risk of metabolic syndrome—a cluster of conditions that includes high blood pressure, obesity, and insulin resistance. Thus, the question of does cardiovascular exercise lower blood pressure can be confidently answered with a resounding yes, provided the activity is regular and of sufficient intensity.

How Cardio Impacts Hormonal Regulation and Inflammation

Understanding how cardio lowers blood pressure also involves examining its influence on hormonal balance and inflammation. Chronic stress is a known contributor to hypertension, largely due to the overproduction of cortisol and adrenaline. These stress hormones cause blood vessels to constrict and heart rate to spike. Exercise serves as a natural stress reliever, decreasing circulating levels of these hormones while stimulating the release of endorphins—mood-enhancing chemicals that promote relaxation and vasodilation.

Additionally, regular aerobic exercise helps decrease systemic inflammation, another critical factor in hypertension. Inflammatory cytokines can damage endothelial cells and stiffen arteries, making it harder for blood to flow efficiently. By mitigating inflammation and reducing stress-related hormone levels, exercise lowers blood pressure both acutely and chronically. These effects are especially profound in individuals with prehypertension or mild hypertension, where lifestyle changes can make a significant impact without the immediate need for medication.

Comparing Exercise to Pharmacological Interventions

One of the most compelling reasons to prioritize physical activity is its non-pharmacological potency. When considering whether does regular exercise lower blood pressure, clinical studies consistently demonstrate that it does—often with effects rivaling those of commonly prescribed antihypertensive medications. For individuals with mild to moderate hypertension, engaging in 150 minutes of moderate-intensity cardio each week can lead to reductions of 5 to 8 mmHg in systolic blood pressure, a result comparable to many first-line medications.

This outcome not only reduces the risk of cardiovascular events but also diminishes the need for pharmaceutical interventions, which often come with side effects. While medication may be necessary for those with severe hypertension, combining it with consistent physical activity amplifies its effectiveness. The synergy between exercise and medication is especially pronounced when patients adhere to both treatment plans, highlighting how does exercise improve blood pressure outcomes across diverse health profiles.

Physical Activity and Long-Term Heart Health

When asking how does exercise lower high blood pressure in the context of long-term health, the benefits extend far beyond the numbers seen on a blood pressure cuff. Regular physical activity strengthens the heart muscle, increases HDL cholesterol (the “good” kind), and reduces triglycerides. These improvements contribute to arterial health and lower the risk of atherosclerosis, a key driver of elevated blood pressure and heart attacks.

Moreover, physical activity reduces visceral fat, the harmful adipose tissue that accumulates around internal organs and contributes to insulin resistance and systemic inflammation. As this fat decreases, metabolic processes normalize, helping regulate blood pressure naturally. The consistent practice of cardio lowers blood pressure over months and years, creating a foundation of cardiovascular resilience that can buffer against age-related declines and chronic illness.

The Role of Exercise in Preventing Hypertension

One of the most valuable aspects of regular exercise is its preventive capacity. While many people begin exercising after a diagnosis, the real power lies in prevention. Can regular exercise lower blood pressure before it becomes a problem? Absolutely. Studies show that individuals who engage in consistent physical activity during early adulthood are significantly less likely to develop hypertension later in life.

This proactive approach helps maintain arterial elasticity and healthy endothelial function even in the presence of other risk factors like stress or poor diet. For those with a family history of hypertension, physical activity acts as a protective buffer, reducing genetic susceptibility through epigenetic changes that favor vascular health. In this sense, asking does working out help lower blood pressure is not merely a question of treatment, but one of prevention and long-term wellness planning.

Best Cardio Practices for Blood Pressure Management

Choosing the best cardio for blood pressure management requires a combination of consistency, intensity, and enjoyment. While there is no one-size-fits-all approach, certain guidelines can help individuals maximize the cardiovascular benefits of exercise. Moderate-intensity aerobic activity, such as walking at a brisk pace, is often recommended for its accessibility and sustainability. More vigorous options, including running, interval training, or rowing, can offer enhanced benefits for those with higher fitness levels.

Regardless of the chosen activity, the most important factor is adherence. The benefits of exercise lower blood pressure only when maintained over time. Incorporating daily movement, even in small increments, helps regulate vascular tone, optimize autonomic function, and reduce resting pressure levels. In this context, the phrase best cardio to lower blood pressure is not about one specific workout but about the regular integration of movement into one’s lifestyle. Exploring different modalities also keeps routines engaging, reducing the risk of burnout and promoting lifelong adherence.

The Interplay Between Physical Fitness and Blood Pressure Variability

Beyond lowering average readings, regular exercise plays a role in reducing blood pressure variability—a lesser-known but equally important factor in cardiovascular risk. Fluctuations in blood pressure from day to night or in response to stress can strain the heart and increase the likelihood of adverse events. Exercise helps stabilize these fluctuations by improving baroreceptor sensitivity. Baroreceptors are sensors in the cardiovascular system that detect pressure changes and help the body regulate them.

When these receptors function optimally, the body can maintain stable blood pressure even in the face of emotional or physical stress. This aspect explains why does exercise help blood pressure stability, particularly in individuals with labile or stress-induced hypertension. Furthermore, improved heart rate variability, a marker of autonomic nervous system health, complements this benefit, showcasing the multifaceted ways exercise contributes to cardiovascular equilibrium.

How Much Is Enough? Frequency and Duration for Results

Understanding how much activity is needed to see results is key to implementing an effective exercise plan. Research suggests that most people experience meaningful reductions in blood pressure with at least 30 minutes of moderate aerobic activity five days a week. However, this doesn’t mean that more is always better. Overtraining can lead to increased stress hormone production, which might counteract the beneficial effects.

Balance is essential. Those who are new to exercise should begin gradually, allowing the body to adapt. Progress can be measured not only by reductions in blood pressure but also by improvements in endurance, energy, and mental clarity. Importantly, the effects of exercise lower blood pressure most effectively when combined with other lifestyle changes, such as improved sleep, balanced nutrition, and stress management. Taken together, these habits create a supportive environment in which cardiovascular health can thrive.

Practical Considerations and Barriers to Physical Activity

Despite the overwhelming evidence, many individuals struggle to incorporate regular exercise into their routines. Time constraints, physical limitations, or lack of motivation can all serve as barriers. Understanding how does physical activity affect blood pressure provides powerful motivation, but implementation requires strategy. Setting realistic goals, seeking support from health professionals, and tracking progress can help maintain consistency.

For those with physical limitations, low-impact options like swimming or cycling on a stationary bike can be just as effective. Even regular walking has been shown to reduce both systolic and diastolic pressure, especially when paired with mindful breathing or meditation. Importantly, exercise should not feel like a punishment but rather an act of self-care. Embracing this perspective can transform the experience, increasing long-term adherence and amplifying the positive impact on blood pressure.

The Role of Exercise in a Broader Lifestyle Framework

While physical activity is a cornerstone of blood pressure management, its effectiveness is maximized when integrated into a broader lifestyle framework. Diet, sleep, stress, and social support all play integral roles in cardiovascular health. A diet rich in whole foods, potassium, magnesium, and low in sodium complements the effects of exercise. Similarly, quality sleep and adequate rest help maintain hormonal balance and prevent the overactivation of the sympathetic nervous system.

Social support and accountability can further enhance commitment to an exercise regimen. Whether through group fitness classes, walking partners, or online communities, connection fosters motivation. In this holistic context, understanding how does physical activity reduce blood pressure becomes part of a larger narrative of self-empowerment and sustainable health. Combining knowledge with action transforms the simple act of movement into a powerful therapeutic tool.

Frequently Asked Questions: How Does Exercise Lower Blood Pressure?

1. Can specific types of cardiovascular training provide faster results for blood pressure control? Yes, interval-based cardiovascular training—such as high-intensity interval training (HIIT)—has been shown to provide quicker reductions in blood pressure, especially among individuals with limited time or those who are prehypertensive. Unlike steady-state cardio, HIIT alternates short bursts of high-intensity effort with active recovery, which enhances vascular elasticity and improves endothelial function more rapidly. This approach demonstrates that not only does cardiovascular exercise lower blood pressure, but its structure and intensity can influence the speed of results. For people looking to optimize time efficiency, integrating short HIIT sessions into their weekly routine may be a compelling alternative. However, this method should be approached cautiously and under professional supervision, particularly for those with a history of cardiovascular disease.

2. Why might some individuals not experience significant reductions in blood pressure from exercise? Although exercise lowers blood pressure for most people, the magnitude of benefit can vary based on genetic predispositions, medication use, and existing comorbidities. Individuals with salt sensitivity or kidney dysfunction may see slower progress, as their bodies retain more fluid and react differently to vascular signals. Additionally, if someone is on beta-blockers or calcium channel blockers, these medications can blunt heart rate responses and mask improvements. Nonetheless, even if blood pressure readings do not shift dramatically, underlying physiological changes—such as improved arterial compliance and heart efficiency—still occur. Therefore, even when visible changes seem minimal, regular exercise continues to help lower blood pressure on a cellular and systemic level.

3. How does physical activity affect blood pressure throughout a 24-hour cycle? Exercise does more than lower blood pressure during and immediately after a workout—it also modifies the circadian rhythm of blood pressure regulation. Research shows that consistent physical activity helps normalize nocturnal dipping, a natural decline in blood pressure during sleep that is crucial for cardiovascular health. When nocturnal dipping is impaired, individuals are at higher risk for stroke and cardiac events. By supporting this pattern, physical activity not only helps lower blood pressure in the short term but also stabilizes long-term fluctuations. This reinforces the broader impact of how physical activity reduces blood pressure beyond the visible numbers on a cuff.

4. Can resistance training support the effects of cardio in lowering blood pressure? Absolutely. While cardio reduces blood pressure most prominently, resistance training offers complementary benefits by enhancing muscular strength, metabolic rate, and insulin sensitivity. Isometric exercises—such as planks or wall sits—have been specifically shown to reduce resting systolic and diastolic pressures over time. When paired with aerobic routines, strength-based workouts improve overall vascular function, reduce arterial stiffness, and increase lean muscle mass, which contributes to better blood flow. So, while cardio is often labeled the best cardio for blood pressure, resistance training still plays a crucial role in any comprehensive regimen. A balanced exercise program ensures that multiple physiological systems are simultaneously optimized for cardiovascular health.

5. What psychological benefits of exercise indirectly help reduce blood pressure? Exercise plays a substantial role in reducing stress, anxiety, and symptoms of depression—all of which are tied to elevated blood pressure. When we ask why does exercise lower blood pressure, part of the answer lies in its ability to modulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and reduce cortisol output. Chronic stress triggers persistent vasoconstriction and inflammatory signaling, both of which elevate baseline pressure. Regular movement releases endorphins and improves vagal tone, helping the body return to a state of physiological calm. In this way, the mental health benefits of physical activity directly reinforce its cardiovascular effects, creating a holistic response that explains why exercise decreases blood pressure on multiple levels.

6. How do temperature and climate affect the blood pressure-lowering benefits of exercise? Interestingly, climate can influence the degree to which exercise lowers blood pressure. In colder weather, vasoconstriction is more pronounced, which may initially elevate blood pressure during outdoor activity. However, the body adapts over time, and the net benefit of consistent movement still applies. In warmer climates, vasodilation occurs more readily, potentially amplifying the effects of cardio. Regardless of location, hydration becomes critical—as dehydration can lead to transient blood pressure increases during or after exercise. Ultimately, while climate may influence short-term fluctuations, it does not negate the long-term effectiveness of exercise in helping lower blood pressure consistently.

7. How can older adults safely use exercise to reduce blood pressure without overexerting themselves? For older adults, the question of how does exercise lower high blood pressure often intersects with safety concerns. Low-impact options such as water aerobics, tai chi, or elliptical training can significantly reduce cardiovascular strain while still promoting vascular flexibility. These exercises help maintain joint integrity and balance while enhancing heart and lung function. Importantly, seniors should focus on gradual progression and incorporate rest days to allow for proper recovery. With proper guidance, even modest levels of physical activity can lower blood pressure and improve quality of life well into older age.

8. What role does hydration play in exercise’s impact on blood pressure? Hydration is often overlooked in the conversation about how does exercise improve blood pressure, yet it is crucial. Proper fluid balance helps regulate blood volume, which in turn affects cardiac output and vascular resistance. When dehydrated, the body compensates by constricting blood vessels and increasing heart rate—both of which can elevate blood pressure. Drinking water before, during, and after workouts ensures that the circulatory system remains efficient and responsive. In this way, hydration acts as a silent partner in the relationship between physical activity and blood pressure regulation.

9. Are wearable fitness trackers effective tools for managing blood pressure through exercise? Yes, modern fitness trackers can be valuable in understanding how physical activity affects blood pressure in real time. While these devices may not replace clinical measurements, many include heart rate variability (HRV) and estimated VO2 max, both of which correlate with cardiovascular health. Tracking trends in resting heart rate, activity levels, and even sleep quality provides actionable insights for optimizing routines. Additionally, the behavioral component of tracking—setting goals and receiving feedback—can increase motivation and adherence. By supporting consistency, these tools indirectly help lower blood pressure and sustain healthy habits over time.

10. What emerging research is exploring new ways exercise lowers blood pressure? Recent studies are investigating the role of gut microbiota in modulating the blood pressure response to exercise. Some researchers suggest that certain bacterial strains activated by physical activity may contribute to nitric oxide production and inflammation control, both of which are mechanisms through which exercise reduces blood pressure. Additionally, genetic research is exploring how individual DNA variations affect responsiveness to different exercise types. This could lead to personalized exercise prescriptions tailored to one’s unique genetic and microbiome profile. As science continues to explore why does exercise reduce blood pressure in some people more than others, the future of hypertension prevention may lie in precision exercise medicine.

Conclusion: Why Exercise Lowers Blood Pressure and Builds a Healthier Future

In the ever-evolving conversation about cardiovascular wellness, the question of how does exercise lower blood pressure reveals a profound and empowering truth: our bodies are designed to respond positively to movement. From enhancing vascular elasticity and promoting hormonal balance to reducing inflammation and improving autonomic control, the physiological pathways through which exercise lowers blood pressure are as complex as they are encouraging. These benefits extend beyond temporary relief, contributing to a resilient cardiovascular system capable of withstanding life’s challenges.

For those wondering does exercise help lower blood pressure or why does exercise reduce blood pressure, the evidence is clear and robust. Physical activity, particularly cardiovascular exercise, is a scientifically supported, highly accessible strategy for improving blood pressure outcomes. It is not merely an adjunct to medication or a weight loss tool but a frontline approach to preventing and managing hypertension. The consistency with which exercise lowers blood pressure makes it one of the most powerful tools available for long-term heart health.

As we shift toward more holistic and proactive models of healthcare, integrating regular exercise into our daily routines is no longer a luxury but a necessity. Whether you’re just beginning your fitness journey or refining your current regimen, know that every step, every breath, and every heartbeat during physical activity is a step toward lower blood pressure, greater vitality, and a stronger, more resilient heart.

Was this article helpful? Don’t let it stop with you. Share it right now with someone who needs to see it—whether it’s a friend, a colleague, or your whole network. And if staying ahead on this topic matters to you, subscribe to this publication for the most up-to-date information. You’ll get the latest insights delivered straight to you—no searching, no missing out.

Further Reading:

The Best Exercise to Lower Your Blood Pressure? It’s Not What You Think It Is

Aerobic Exercise Reduces Blood Pressure in Resistant Hypertension