In recent years, the connection between nutrition and mental health has become a subject of increasing interest among researchers, clinicians, and the general public. While traditional approaches to treating anxiety and panic disorders have primarily centered on therapy and medication, an emerging body of evidence suggests that what we eat can also significantly influence how we feel. Understanding how diet may affect mental health, especially in relation to foods that cause anxiety and panic attacks, is essential for developing a more comprehensive, holistic approach to emotional well-being.

You may also like: How to Stop Emotional Eating and Regain Control: Mindful Nutrition Strategies That Support a Healthier Lifestyle

Our relationship with food is deeply personal and culturally embedded, yet it also has powerful physiological effects that are often underestimated. Many individuals who experience anxiety or mood fluctuations may not immediately consider dietary habits as a contributing factor. However, when we examine the biochemical interplay between food and the brain, it becomes clear that our meals do more than fuel our bodies—they actively shape our mental and emotional landscape. For instance, certain foods have been found to trigger physiological stress responses, while others can provide stabilizing nutrients that support the nervous system.

This article delves into the scientific, nutritional, and emotional dimensions of the food-anxiety connection. It explores key dietary culprits that may exacerbate anxiety, discusses the biochemical mechanisms behind these effects, and provides practical strategies for identifying and minimizing dietary triggers. Whether you have experienced anxiety and loss of appetite or find that eating less makes you anxious, understanding how your food choices affect your brain chemistry can be empowering. In doing so, this knowledge can help inform more mindful eating practices and support a healthier lifestyle.

The Biochemical Bridge Between Diet and Anxiety

At a cellular level, food directly impacts the neurotransmitters that regulate mood. Neurotransmitters like serotonin, dopamine, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) are all synthesized from nutrients that we obtain through our diet. When these nutrients are lacking or imbalanced, neurotransmitter production may be impaired, potentially increasing vulnerability to stress, anxiety, and mood disorders.

One notable example is the amino acid tryptophan, a precursor to serotonin, which is often referred to as the “feel-good” neurotransmitter. If the diet is deficient in tryptophan-rich foods such as turkey, eggs, or seeds, serotonin levels may drop, leading to heightened feelings of irritability and anxiousness. Furthermore, imbalances in blood sugar caused by excessive sugar consumption or long gaps between meals can also disrupt brain function. This can trigger a fight-or-flight response that resembles a panic attack. Thus, for many, a closer look at daily food intake reveals how diet may increase the chance of anxiety and related symptoms.

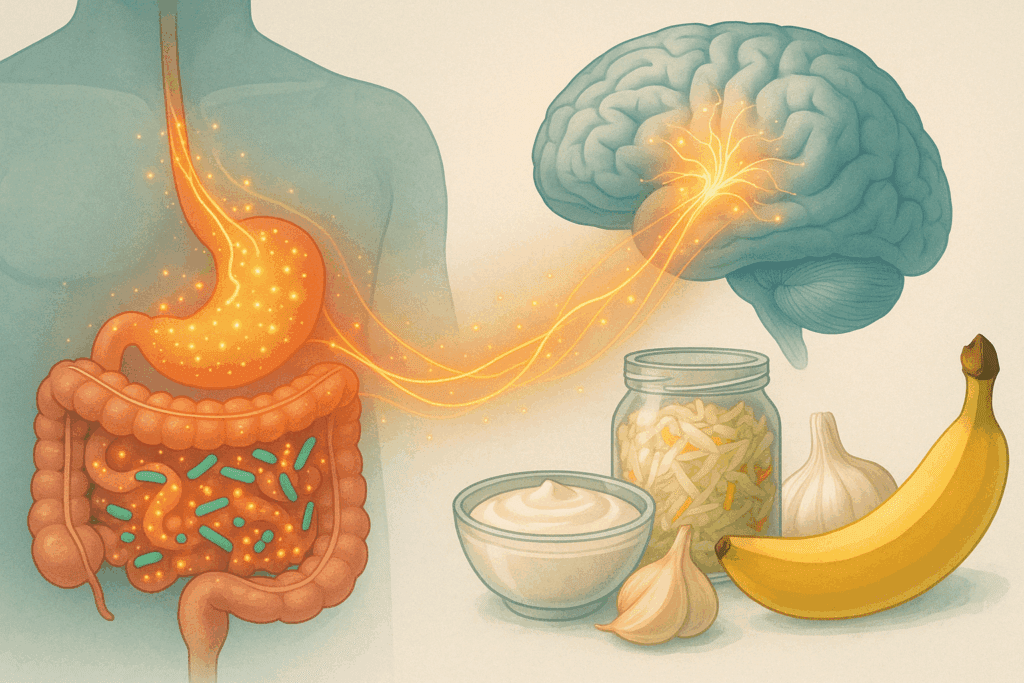

Additionally, research shows that inflammation in the gut and the body can affect mental health. A poor diet, particularly one rich in processed foods, can disrupt the gut microbiome, the community of bacteria in our digestive tract. This disruption may contribute to systemic inflammation and influence the gut-brain axis—the bidirectional communication system between the gastrointestinal system and the central nervous system. As such, anxiety linked to food is not merely anecdotal; it has a growing base of scientific support.

Foods That May Contribute to Anxiety and Panic Attacks

One of the most well-documented contributors to diet-related anxiety is sugar. Many individuals report feeling jittery, irritable, or panicked after consuming large amounts of sugary foods. Scientific evidence supports this, showing that excess sugar can cause spikes and crashes in blood glucose levels, which in turn affect mood stability. The question “can sugar cause anxiety” is frequently posed in clinical discussions, and the answer appears to be a cautious yes—particularly when sugar is consumed in large quantities without balancing it with fiber or protein. Similarly, the concern “can sugar make you anxious” reflects the lived experience of many who notice heightened stress levels after indulging in sweets.

Artificial sweeteners, often used as sugar substitutes, may not be a better option. Compounds like aspartame have been shown in some studies to affect brain chemistry and may exacerbate symptoms of anxiety and depression in sensitive individuals. Therefore, the idea that sugar alternatives are automatically safer for mental health may be misleading.

Caffeine is another major dietary trigger for anxiety. While a cup of coffee may enhance alertness and focus for some, for others it can induce symptoms that closely mimic panic attacks—racing heart, restlessness, and gastrointestinal distress. For individuals already prone to anxiety disorders, caffeine consumption can be particularly problematic. It’s important to recognize how your food creates anxiety in these instances, as each individual’s sensitivity varies.

Highly processed foods also belong in the category of foods that contribute to anxiety. These products are often loaded with preservatives, artificial colors, and trans fats, all of which may impair brain function or disrupt mood regulation. High intake of omega-6 fatty acids—common in processed oils—without balancing them with omega-3s from fish or flaxseed may promote inflammation and worsen mental health outcomes.

Finally, certain food additives and allergens can trigger physical reactions that resemble or exacerbate anxiety. Gluten, dairy, and food dyes have been implicated in heightened anxiety responses among some populations, particularly those with sensitivities or autoimmune disorders. For individuals who notice symptoms like increased heart rate or nausea after meals, it may be worth exploring whether specific foods trigger anxiety and panic attacks.

Appetite Disturbances and Their Link to Anxiety

A frequently overlooked but critical component of the diet-anxiety relationship is appetite. Individuals suffering from anxiety often experience appetite changes, ranging from compulsive eating to complete appetite suppression. For some, the connection is so profound that they begin to ask, “Can anxiety cause loss of appetite?” or “Does anxiety cause appetite loss?” These are more than casual questions; they reflect the real struggle of individuals attempting to nourish themselves in the face of overwhelming internal distress.

Scientific literature supports the claim that anxiety can lead to appetite disturbances. The body’s stress response, governed by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, often suppresses appetite as part of the fight-or-flight mechanism. This makes sense from an evolutionary standpoint—if we are under threat, digestion becomes a secondary priority. However, in a modern context where stress is chronic rather than acute, this can result in long-term reductions in food intake and nutritional deficiencies.

For some individuals, the issue manifests as an inability to feel hunger cues, while others may feel nauseous at the thought of food. These experiences align with terms such as anxiety and loss of appetite or anxiety lack of appetite, and they highlight the urgent need for nutritional strategies that support both body and mind. Similarly, those experiencing no appetite due to stress may struggle to find meals that feel palatable or comforting, further complicating recovery.

In contrast, there are also people who report that eating less makes them anxious. This is not surprising given the brain’s reliance on glucose and other nutrients for optimal function. Skipping meals or following restrictive diets may lead to mood instability, fatigue, and heightened anxiety, particularly for those who are already vulnerable. When blood sugar drops too low, the brain interprets this as a crisis, sending distress signals throughout the body. This can create a feedback loop of anxiety linked to food intake, where individuals feel anxious when they eat and even more anxious when they don’t.

Recognizing Foods That Trigger or Worsen Anxiety

While individual food sensitivities vary, a growing body of research has identified several common dietary culprits that can act as anxiety disorder foods to avoid. These include refined carbohydrates, processed meats, high-sodium snacks, and fried foods. These items are low in nutritional value but high in ingredients that may interfere with mood regulation.

Refined carbohydrates, such as white bread and pastries, are quickly digested and can cause rapid spikes in blood sugar. This not only affects physical health but may also lead to mood crashes and increased irritability. When asking “why do I get anxiety after eating,” the answer often lies in these glycemic fluctuations. Similarly, processed meats and salty snacks can lead to fluid retention and increased blood pressure, which some individuals may interpret as anxiety symptoms.

Alcohol and recreational substances also deserve mention. Though they may provide temporary relief, alcohol is a depressant that can impair judgment and disrupt sleep, ultimately exacerbating anxiety. In this context, it becomes clear that anxiety foods to avoid include more than just sugar and caffeine; they encompass a broader spectrum of substances that interact with brain chemistry.

The Role of Stress and Appetite Regulation

Chronic stress can profoundly influence dietary habits and appetite, making it a key factor in the conversation about foods that cause anxiety and panic attacks. The physiological stress response suppresses appetite in the short term, but over time it can lead to dysregulated eating behaviors. This is often observed in individuals who oscillate between periods of not eating and episodes of emotional or binge eating. The question “can stress cause loss of appetite” or “does stress cause lack of appetite” becomes even more relevant in this cyclical pattern.

Stress and loss of appetite often go hand in hand, particularly in high-pressure environments like workplaces or academic settings. The body produces higher levels of cortisol during times of stress, which can dull hunger cues or, conversely, drive cravings for high-fat, high-sugar comfort foods. This paradox creates a complex feedback loop: stress alters appetite, irregular eating worsens mental health, and poor nutrition further compounds anxiety. As a result, it’s crucial to explore how to fix loss of appetite due to anxiety with methods that address both physiological and emotional factors.

Strategies for Mitigating Diet-Related Anxiety

Fortunately, there are practical steps individuals can take to reduce anxiety symptoms through dietary adjustments. One effective strategy is to adopt a nutrient-dense, whole-foods-based diet that emphasizes complex carbohydrates, lean proteins, healthy fats, and abundant fruits and vegetables. These foods help stabilize blood sugar, reduce inflammation, and support neurotransmitter production.

Including magnesium-rich foods like leafy greens, nuts, and legumes can be beneficial, as magnesium plays a key role in calming the nervous system. Similarly, omega-3 fatty acids from sources like salmon, flaxseed, and walnuts have anti-inflammatory properties and may help regulate mood. Individuals wondering if their diet is exacerbating anxiety may find that reducing or eliminating foods that trigger anxiety brings substantial relief.

In addition to making informed food choices, mindful eating practices can also support mental health. Slowing down during meals, focusing on flavors and textures, and tuning in to hunger and satiety cues can reduce emotional eating and promote a more balanced relationship with food. These practices can be especially helpful for those dealing with stress and anxiety loss of appetite, as they help restore a sense of control and pleasure in eating.

Seeking support from healthcare professionals, such as a registered dietitian or integrative physician, can also provide personalized insights. These experts can help identify hidden food sensitivities or nutrient deficiencies that may be contributing to anxiety. Moreover, they can help design a dietary plan that supports both physical health and emotional resilience.

Understanding the Gut-Brain Axis in Anxiety Management

The gut-brain axis—the complex communication network between the gastrointestinal system and the central nervous system—has emerged as a key player in mental health. Gut health influences brain function through various pathways, including immune signaling, neurotransmitter production, and hormonal regulation. Disruptions in this axis can contribute to anxiety, depression, and other mood disorders.

One of the most promising developments in this field is the recognition that probiotics and prebiotics can modulate the gut microbiome in ways that benefit mental health. Fermented foods like yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, and kimchi introduce beneficial bacteria that support digestive and emotional health. Meanwhile, prebiotic fibers found in garlic, onions, and bananas provide nourishment for these bacteria. This synergy may help alleviate anxiety symptoms and improve overall well-being.

People who notice anxiety linked to food may benefit from incorporating gut-friendly meals into their routines. Additionally, reducing intake of processed foods and artificial additives can support microbiome diversity and reduce systemic inflammation. As scientists continue to explore the intricate web of connections between diet, gut health, and mental wellness, the gut-brain axis remains a powerful focal point for future therapies.

Frequently Asked Questions: Diet, Anxiety, and Appetite

What are some surprising ways that food sensitivity can trigger anxiety symptoms?

Food sensitivities can activate immune responses that go beyond digestive discomfort, potentially leading to systemic inflammation and mood disturbances. For individuals with heightened sensitivity to certain foods, even a small exposure can disrupt the balance of neurotransmitters like serotonin and GABA. This helps explain how your food creates anxiety without you realizing it—a slice of bread or a dash of soy sauce might set off a chain reaction that leaves you feeling on edge. Interestingly, foods that cause anxiety and panic attacks are not always immediately obvious and often require elimination diets or allergy testing to identify. Since food sensitivities are deeply individual, identifying which foods trigger anxiety can require a nuanced, case-by-case approach supported by medical professionals.

Can anxiety cause loss of appetite even when someone is otherwise physically healthy?

Absolutely. Anxiety and loss of appetite are often tightly intertwined, even in individuals with no other apparent health issues. The body’s stress response involves the release of hormones like cortisol and adrenaline, which can shut down the digestive process. Over time, repeated episodes may condition the body to associate eating with discomfort or unease, leading to chronic anxiety lack of appetite. What complicates matters further is that the physical sensation of hunger may be masked by the presence of anxiety, which makes individuals less likely to eat even when they need nourishment.

Why do some people say eating less makes them anxious?

The idea that eating less makes me anxious isn’t as contradictory as it sounds. When the body is underfed, it experiences a drop in blood glucose levels, which the brain interprets as a threat. This activates the same stress pathways that are triggered by external anxiety-inducing situations. Moreover, the body might release adrenaline to compensate for low energy, mimicking the feeling of anxiety. In these cases, consistent nourishment can act as a stabilizing force, highlighting how foods that contribute to anxiety are not just about what you eat but also when and how often you eat.

Is there a link between sugar and panic attacks?

Yes, there is mounting evidence that sugar intake can influence panic responses, especially in individuals with blood sugar sensitivity. Large spikes in blood glucose can lead to reactive hypoglycemia, where the body rapidly overcompensates and crashes blood sugar levels. This crash can produce symptoms like dizziness, sweating, and heart palpitations—which are nearly indistinguishable from a panic attack. That’s why the question “can sugar cause anxiety” or “can sugar make you anxious” is valid and supported by both anecdotal reports and clinical studies. It’s not just about sweets; even high-glycemic foods like white bread or sugary drinks can be considered foods that cause anxiety and panic attacks in susceptible individuals.

How can I tell if my anxiety is linked to what I’m eating?

Tracking symptoms and dietary intake simultaneously can be a powerful tool for identifying anxiety linked to food. Using a journal to log meals, stress levels, and physical symptoms over the course of a few weeks may reveal correlations you wouldn’t otherwise notice. If you find recurring anxiety episodes after eating certain meals, especially those rich in processed or sugary foods, you may be dealing with foods that trigger anxiety. Additionally, if you notice stress and loss of appetite occurring consistently after consuming specific ingredients, that could be another clue. Consulting a registered dietitian or integrative health practitioner can help interpret these patterns in a medically sound way.

Can stress alone lead to a long-term loss of appetite?

Yes, chronic stress can desensitize hunger signals over time, resulting in a persistent lack of appetite. This goes beyond short-term reactions and may lead to long-standing nutritional deficiencies if not addressed. When people wonder “can stress cause lack of appetite” or “can stress lead to loss of appetite,” the answer is unequivocally yes—especially in high-pressure environments where stress is prolonged and unrelenting. Over time, this can evolve into stress and anxiety loss of appetite, where the body is not only undernourished but also stuck in a loop of emotional and physiological depletion. Re-establishing regular eating patterns often requires addressing both the psychological and nutritional components of stress.

What are some commonly overlooked anxiety disorder foods to avoid?

Beyond sugar and caffeine, other anxiety disorder foods to avoid include aged cheeses, fermented sausages, and even certain fruits like bananas or avocados in sensitive individuals due to their tyramine content. Monosodium glutamate (MSG), a flavor enhancer found in many processed foods, is another hidden trigger that may cause excitatory reactions in the nervous system. Even excessive intake of sodium can subtly contribute to blood pressure fluctuations that feel like anxiety. These foods that contribute to anxiety may fly under the radar because they aren’t inherently “unhealthy” for everyone, but for those with a predisposition to anxiety, they can be highly reactive. Paying attention to ingredient labels and reducing processed food intake can make a significant difference.

Why do some people experience anxiety after meals even when eating healthy?

The phenomenon of “why do I get anxiety after eating” can stem from a variety of sources unrelated to food quality. For instance, those with digestive conditions like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) may experience post-meal bloating and discomfort, which then gets misinterpreted by the brain as a threat, triggering anxiety. Also, individuals with a history of eating disorders or food trauma may experience anticipatory anxiety around meals, even if they are eating nutrient-dense foods. In such cases, anxiety linked to food is less about the ingredients and more about the emotional associations with eating. Mindful eating, therapy, and stress-reduction techniques can help retrain the body’s response to food.

How can someone recover their appetite when anxiety has made eating difficult?

To address how to fix loss of appetite due to anxiety, it’s crucial to create a non-threatening eating environment. Start by consuming small, easy-to-digest meals at regular intervals rather than forcing large meals all at once. Smoothies, broths, and nutrient-dense snacks can be easier to tolerate during periods of intense stress. Incorporating rituals like calming music, aromatherapy, or light stretching before meals can also shift the body into a parasympathetic state, encouraging digestion. This approach not only tackles anxiety and loss of appetite but also rebuilds trust in the eating process, helping reverse patterns like no appetite stress or losing appetite stress.

Does diet increase chance of anxiety in people with no prior mental health conditions?

Surprisingly, yes. Even individuals without a formal diagnosis of anxiety can experience mood disturbances tied to their dietary habits. Diets high in processed foods, refined sugars, and artificial additives can alter gut microbiota and lead to subtle inflammation, which may affect mood regulation. Over time, these disruptions may escalate, leading individuals to ask, “does diet increase chance of anxiety even if I was fine before?” The answer is yes—especially in environments where stress and poor nutrition coexist. Preventative strategies like focusing on whole foods, stabilizing blood sugar, and avoiding foods that trigger anxiety can serve as effective tools for long-term emotional resilience.

Conclusion: Reclaiming Mental Wellness by Rethinking the Role of Diet in Anxiety

In the evolving landscape of mental health care, the role of nutrition deserves far more attention than it has traditionally received. For many individuals, understanding how diet may affect mental health opens a new avenue of hope and healing. From identifying foods that cause anxiety and panic attacks to recognizing the subtle signs of appetite loss due to anxiety, every bite we take has the potential to influence our emotional state. Whether the concern is “can anxiety cause decreased appetite” or “can sugar give you anxiety,” the evidence increasingly points to the need for a dietary strategy as part of a broader mental wellness plan.

This knowledge empowers individuals to make choices that support—not sabotage—their mental health. By being mindful of how sugar, caffeine, processed foods, and food allergens affect our bodies and minds, we can take meaningful steps toward reducing anxiety symptoms. Simultaneously, by nourishing ourselves with whole, nutrient-rich foods and honoring the body’s natural cues, we can foster resilience in both brain and body. As our understanding deepens, so does our ability to harness the power of food as medicine for the mind.

Ultimately, diet is not a standalone cure for anxiety or panic disorders, but it is an essential component of an integrative approach to wellness. By addressing the question “does diet increase chance of anxiety” through research-based insights and practical strategies, we can move toward a future where food and mental health are no longer considered separate spheres, but intrinsically linked parts of a holistic health journey.

Was this article helpful? Don’t let it stop with you. Share it right now with someone who needs to see it—whether it’s a friend, a colleague, or your whole network. And if staying ahead on this topic matters to you, subscribe to this publication for the most up-to-date information. You’ll get the latest insights delivered straight to you—no searching, no missing out.

Further Reading:

The 4 Worst Foods for Your Anxiety

Coping with anxiety: Can diet make a difference

Diet and Anxiety: A Scoping Review

Disclaimer

The information contained in this article is provided for general informational purposes only and is not intended to serve as medical, legal, or professional advice. While NewsHealthWatch strives to present accurate, up-to-date, and reliable content, no warranty or guarantee, expressed or implied, is made regarding the completeness, accuracy, or adequacy of the information provided. Readers are strongly advised to seek the guidance of a qualified healthcare provider or other relevant professionals before acting on any information contained in this article. NewsHealthWatch, its authors, editors, and contributors expressly disclaim any liability for any damages, losses, or consequences arising directly or indirectly from the use, interpretation, or reliance on any information presented herein. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policies or positions of NewsHealthWatch.